Presented by:

The U.K. has a new head of business and energy, and he means oil and gas—in addition to other fuels. Secretary Kwasi Kwarteng ordered a new shale development report from the British Geological Survey (BGS) on April 5.

Nothing fancy. Something quick. It was due at the end of this past month.

“I want to be clear that this should be a desk-based exercise,” he wrote to the BGS. He wasn’t asking for more test wells or additional seismic monitoring. “The aim would be to assess any progress in the scientific understanding … to consider next steps.”

As for fossil-fuel protesters, he tweeted on April 13: “My message to XR [Extinction Rebellion] activists gluing themselves … to my department [building]: You cannot—and we won’t—switch off domestic oil and gas production. Doing so would put energy security, jobs and industries at risk and would simply increase foreign imports, not reduce demand.”

“

The Bowland has the same kind of characteristics as the Fayetteville and Barnett. It’s in the dry-gas window, which is actually good.”—Kent Bowker

It’s a turnabout from a U.K. energy policy that retreated just a few years ago when confronted by protesters, such as fashion designer Joe Corre, son of designer and activist Dame Vivienne Westwood. Kwarteng presented to one of his alma maters, Harvard Kennedy School, the day he wrote to the BGS. “Transforming our energy system is no longer just about hitting net-zero targets and tackling climate change—as important as they are. It is also about national security,” he said.

Among those leading exploration of U.K. shale this past decade was Sir Jim Ratcliffe, founder and chairman of privately held, London-based chemicals manufacturer Ineos.

He wrote in The Daily Telegraph on April 10: “The sad reality of the short history of the U.K. shale industry was that the science was totally ignored, and our politicians reacted to a false public perception of the so-called dangers by introducing a moratorium on development. Apparently the influential voice of a fashion designer carries more weight than any number of scientific experts.”

Dan Steward and Kent Bowker, geologists who were part of the Mitchell Energy & Development Corp. team that cracked the code on the Barnett Shale in the late 1990s, were consulting to Ineos as it drilled shale tests.

Also part of the consulting group was Nick Steinsberger, the lead Mitchell petroleum engineer.

Bowker told Oil and Gas Investor, “I’ve got to say, if you read [Ratcliffe’s] letter, he gets about as feisty as I’ve ever seen him in public.”

The U.K. is paying more than $30/MMBtu of natural gas and more than $120/bbl for oil. It’s a net importer of both.

Steward said, “They are desperate for something. They are looking at possibly giving tight reservoirs another chance. Possibly. Putin made them rethink things.”

What shale?

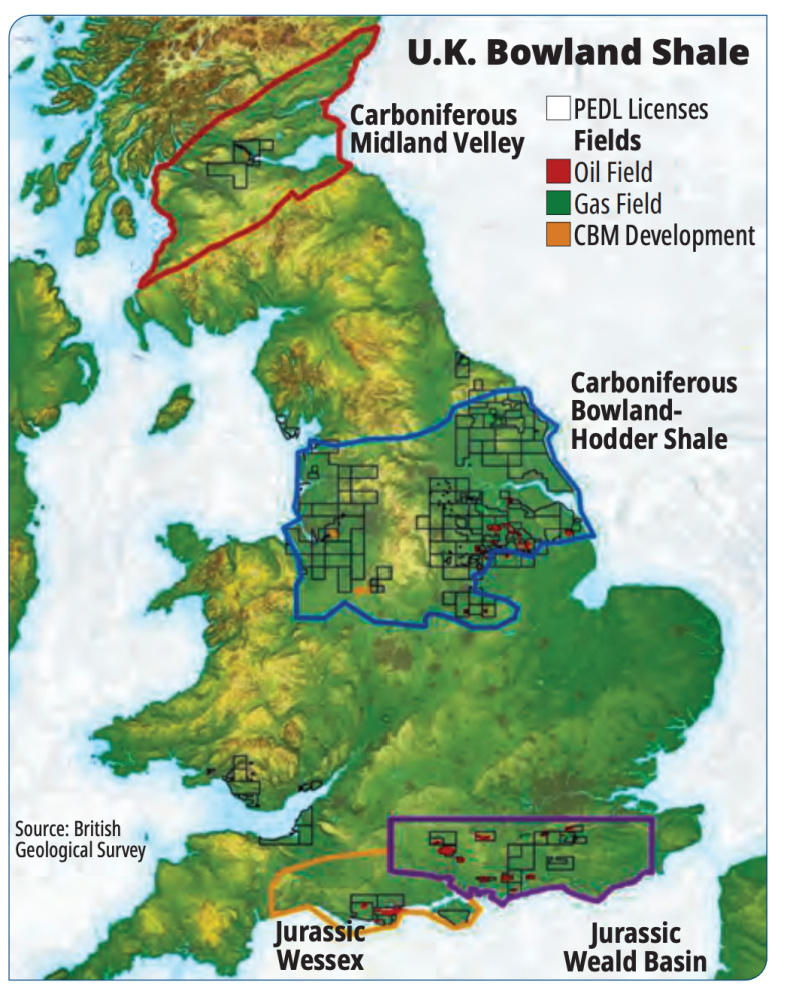

The U.K. has four onshore areas with shale gas development potential, according to the BGS: the Bowland Shale-Hodder mudstone (Carboniferous) in northern England; the Midland Valley (Carboniferous) in southern Scotland; and the Weald Basin ( Jurassic) and Wessex area ( Jurassic) in southern England.

The BGS estimates 1,300 Tcf of gas in place (P50) in the Bowland and 4.4 Bbbl of oil in place in the Weald. The shale in southern Scotland might contain 80 Tcf and 6 Bbbl. An estimate was not made for the Wessex area due to insufficient data.

The Bowland, which was deposited during the Visean and Namurian stages of the Carboniferous period when the U.K. was located at the equator, extends offshore too—west under the Irish Sea and east under the North Sea. Gas in place for it and the Hodder is between 822 Tcf and 2,281 Tcf based on one analysis, the BGS reported; another analysis suggests it might be 140 Tcf.

In southern Scotland in the Midland Valley, the shale has 2% to 6% organic carbon content. The BGS reports an estimate of between 49 Tcf and 137 Tcf of gas in place.

The Bowland is also found on England’s southern coast. But the potential is unknown, according to the BGS.

Halted

Shale tests were halted in the U.K. in 2019 after a 2.9 magnitude earthquake was measured as U.K.- based E&P Cuadrilla Resources Ltd. completed in the Bowland at Preston New Roads about 6 miles from the Irish Sea.

“There, it’s completely different geologically,” Bowker said. “Where they are, the Bowland is very thick, but it’s also very faulted. Ineos had the opportunity to be in that area, but Dan and I suggested they stay out of there mainly because it’s faulted.”

Faults are where you “lose your frac.” Bowker said, “It’s not going to work well. Our friends at Cuadrilla induced some earthquakes. And that’s what stopped the process in the whole country.”

The geology to the east, where Ineos was testing in its leasehold and in some leasehold operated by a joint-venture partner, U.K.-based IGas Energy Plc, “is more benign,” though.

“It’s not structurally complex. And we believe it’s a lot quieter tectonically. Induced seismicity should be much less of a threat where Ineos is.”

Ineos’ tests found the Bowland to be good rock. And it also found a tight-gas sandstone, the Millstone Grit, similar to, “though not at the same scale,” as the Mesaverde of the Piceance Basin and the Morrow/Springer sands of the Oklahoma portion of the Anadarko Basin.

“In fact, they are the same geologic age: Lower Pennsylvanian. It’s a massive basin-center gas deposit. It’s not shale, but it’s possibly very productive,” Bowker said.

In both the shale and the sandstone, “we know the gas is there because we did all the science and the drilling to show that it’s there. Now, we weren’t allowed to try to produce it. We weren’t allowed any kind of completion. So we don’t know exactly how much of it we’re going to produce. We just know there’s a lot there.”

The combination of resource in place and areal extent— possibly hundreds of square kilometers—might make it a Fayetteville-size producer, Bowker estimates.

“[The Bowland] isn’t going to be a huge game changer, like the Marcellus and the Haynesville have been in the U.S. But for the U.K., it’s plenty big.”—Dan Steward

Steward said, “When you consider Britain’s gas requirements are substantially less than ours, it means quite a bit of gas.”

The U.K.’s natural gas consumption in 2019 was 2.9 Tcf; production was 1.4 Tcf, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. In contrast, U.S. gas consumption in 2019 was 32 Tcf; production was 35 Tcf.

U.S. consumption this year is trending to 35 Tcf, with some 7.3 Tcf of that “consumed” by exports via LNG and pipe.

For Europe as a whole, the Bowland “isn’t going to be a huge game changer, like the Marcellus and the Haynesville have been in the U.S.,” Steward said. “But for the U.K., it’s plenty big.”

Resembles

Bowland gas in place closely resembles that of the Barnett and Fayetteville shales, Bowker said. “The Fayetteville has thousands of wells with sandstones above it that are gas-saturated. The Fayetteville always seemed to me to be the most proper analog,” he said.

The Fayetteville is Mississippian-age. Bowker said, “The Mississippian/Pennsylvanian stratigraphy gets complicated in the U.K.; that’s probably why they call the whole thing Carboniferous.

“But the Bowland has the same kind of characteristics as the Fayetteville and Barnett,” Bowker said. “It’s in the drygas window, which is actually good. And there might be some liquids like some parts of the Barnett Shale.”

As for the Bowland’s permeability, porosity and organic content, these are similar to the Barnett.

In terms of the number of benches for stacking horizontals, “I think there’ll be one in the shale play where Ineos is,” Bowker said. “I don’t think there will be multiple ones.”

But in the basin-centered sandstone play above it, there are multiple intervals. He likens it to Jonah and Pinedale fields.

“We’ve got sandstones that are just chock full of gas, and they’re tight. They’re going to require stimulation. And they don’t really produce a lot of water.”

Incomplete completion

Bruce Walker, Enverus regional manager, Europe and Middle East, summarized the shale development attempts in a 2019 blog post. Cuadrilla drilled four Bowland tests between 2010 and 2012, resuming in 2017 at Lancashire in eastern England. One of the wells, Preston New Road, tested up to 0.2 MMcf/d.

It was underwhelming, but “this was despite only fully fracking and completing two out of 41 planned frac stages in the Bowland.” Also, the well was only a vertical.

Meanwhile, the IGas-Ineos partnership found “excellent shale gas potential” in the Millstone Grit above the Bowland in its Tinker Lane well at Nottinghamshire, Walker added.

Another IGas-Ineos’ well, Springs Road, showed 250 meters (820 ft) of the Bowland “and further gas indications in the Millstone Grit and the deeper Arundian Shale.”

In 2016, the U.K. awarded more than 12,000 square kilometers of prospective shale acreage with Ineos getting the most; it had applied for 30 permits.

Walker added that Britain’s Centrica Plc and France’s Engie SA and TotalEnergies SE were, at the time, “waiting in the wings.”

Delineation

What’s needed next is delineation: drilling additional wells across the play, Bowker said. Ineos drilled only two wells before the U.K. shut it down, “but the two wells at least showed there is plenty of gas in place.

“An engineer will tell you, ‘That’s great. But are you going to be able to produce it?’ We weren’t allowed to prove that we could produce it.

“But Dan and I know from our work in the Barnett and all the other plays that we’ve been involved in that the engineering knowhow is there to get the gas out.

“But again, we weren’t allowed to do it.”

He added that resuming tests “to get it out is, politically speaking, a no-brainer.”

Steward noted that, essentially, Ineos wants to use its own money to science the U.K.’s indigenous natural gas—for the U.K. “It’s almost a gimme that the government should say, ‘Yes.’”

At stake

This past February, Cuadrilla plugged its two wells in Lancashire as ordered by the government, according to The Guardian, adding that Cuadrilla’s CEO called the order “ridiculous” while Europe was confronting a gas crisis.

This was four days before Russia invaded Ukraine.

It’s believed that, like in the Marcellus, Putin seeded U.K. anti-fracking campaigns. Interestingly, all have backfired. The U.S. is the world’s No. 1 producer of natural gas and is shipping to the U.K. some of its surplus, while U.S. experts are instructing the U.K. on how it can develop its shale.

Ineos itself is a direct recipient of U.S. shale development, having built tankers to receive Marcellus ethane at an Atlantic terminal and to receive other U.S. ethane from the Houston Ship Channel.

Steward said that, if the U.K. had proceeded with shale development in the past decade, “I don’t think they would be in the position they’re in today.”

Now, possibly, “they have learned enough to start getting enough gas out to take care of themselves.”

But the U.K. has additional surface issues to overcome, Steward added. “When Kent and I first got there, the government was proud to tell us they could issue a permit in a year, whereas it used to take two years.

“And we told them, ‘Look, if it takes a year to get a permit, you’re never going to have a development program.’”

NORTH SEA CONVENTIONALWhile suddenly actively encouraging oil and gas development, the U.K. has also proposed a windfall-profit tax on energy companies. According to Reuters, the 25% tax plan is expected to come with a nearly 100% tax break for capital spent on new oil and gas projects. Reuters quoted Rishi Sunak, the British chancellor, “The more a company invests, the less tax they will pay.” Also this spring, the U.K. approved a Shell Oil Co. gas development, Jackdaw, after having rejected it in October. Jackdaw had been licensed since 1970. Reuters reported that “Shell’s new plan changed the way it processes gas at the Shearwater hub” in regards to handling naturally occurring CO₂. U.K. Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Kwasi Kwarteng tweeted about the Jackdaw approval, “We’re turbocharging renewables and nuclear, but we are also realistic about our energy needs now. “Let’s source more of the gas we need from British waters to protect energy security.” |

‘You’re the highest price’

Bowker said, “It’s interesting that [in Nottinghamshire] not too far away from where we drilled the Springs Road well is a statue that is a twin to one in Ardmore, Okla. The statue commemorates the importation of U.S. drilling crews from southern Oklahoma during World War II.

The statue, “The Oil Patch Warrior,” was dedicated in 1991. During WWII, Ardmore-based Noble Corp. drilled for oil in the U.K.’s Sherwood Forest to surface fuel for the U.S. ally.

“At one time, the U.K. had a vibrant onshore oil and gas industry,” Bowker said. “It still produces oil onshore. It’s not anywhere near what it used to be. But it’s interesting that the citizenry in the U.K. at one time actually celebrated oil and gas.”

The noisemakers are few, though, he added. Out in the countryside, “when we would talk to folks in the restaurants and pubs, most of them understood what we were doing and were supportive.

“As long as you don’t shake their China cabinets,” Bowker said.

Steward added, “When you get away from the radicals, they’re good with it. And I’m sure they would be now, given the price they’re having to pay for fuel.”

Bowker added that an easily dispelled myth circulating in the U.K. is that Ineos “will just export the gas to get the highest price. “I’m like, ‘But you’re the highest price.’”

Besides that, “there’s no way to export the gas from the U.K. All the pipelines flow into the U.K.”

Industrial revolution

Chris Wright presented to the House of Lords in 2014 on how fracking is safely done in the U.S. He was among 1990s frac-design team members involved with eventual breakthroughs on economically completing U.S. shale wells.

He went on to found pressure-pumping operator Liberty Energy Inc., where he is chairman and CEO.

He noted in an Oil and Gas Investor interview at Hart Energy’s DUG Haynesville Conference last year that the Bowland Shale “runs right through the Midlands of England, literally where the industrial revolution began.

“I know the folks and companies in this room, if they brought their technology over to the U.K., could have a shale revolution right there.”

The attempt to develop the shale in the past decade was welcomed by the U.K. manufacturing industry, he added, “and protesters of fewer than a hundred people were able to prevent wells from being drilled and fracked.”

Meanwhile, in Liverpool, which sits on top of the Bowland and is the birthplace of the industrial revolution, “one in three households is without a single employed person living in them,” Wright said.

‘Flick of a political switch’

In his op-ed April 10, Ineos’ Ratcliffe wrote, “The U.K. is in the midst of an energy crisis. … How have we ended up in this situation?”

The North Sea and nuclear power had given the U.K. “an enviable degree of energy independence. … All of that has disappeared, with successive governments of all political colors having no coherent energy policy. Energy policy is a long game.”

But the U.K. has had 27 secretaries of state during the past 50 years, “hardly a recipe for long-term thinking.”

The U.K. now imports 50% of its gas. “We are buying strategic gas supplies for the country on spot deals at the whim of global markets and are reliant for supply on foreign governments with whom we may have fundamental differences.”

In addition, he wrote, U.K. storage capacity is 2% of annual demand. (For comparison, U.S. gas storage is about 14% of domestic demand, excluding exports to Mexico and as LNG, and about 11% of gross demand.)

“Our £250 million investment [in shale tests] did not even get us to first base. We identified significant reserves of gas across the whole of the north of England, but were not allowed to develop a single test well to prove that the technology could be operated safely,” Ratcliffe wrote.

“[This] £250 million of investment [was] destroyed with the flick of a political switch, with no offer of compensation and not even the decency of an apology.”

Shale development takes time, he noted, so if it had not been halted in 2019, “it would, indeed, be having a positive impact today.”

Today, it can only be helpful in countering the next British energy crisis. “Unless we act now, we will be in the same parlous position then.”

Recommended Reading

SilverBow Saga: Investor Urges E&P to Take Kimmeridge Deal

2024-03-21 - Kimmeridge’s proposal to combine Eagle Ford players Kimmeridge Texas Gas (KTG) and SilverBow Resources is gaining support from another large investor.

Benchmark Closes Anadarko Deal, Hunts for More M&A

2024-04-17 - Benchmark Energy II closed a $145 million acquisition of western Anadarko Basin assets—and the company is hunting for more low-decline, mature assets to acquire.

Uinta Basin's XCL Seeks FTC OK to Buy Altamont Energy

2024-03-07 - XCL Resources is seeking approval from the Federal Trade Commission to acquire fellow Utah producer Altamont Energy LLC.

Mesa III Reloads in Haynesville with Mineral, Royalty Acquisition

2024-04-03 - After Mesa II sold its Haynesville Shale portfolio to Franco-Nevada for $125 million late last year, Mesa Royalties III is jumping back into Louisiana and East Texas, as well as the Permian Basin.

Life on the Edge: Surge of Activity Ignites the Northern Midland Basin

2024-04-03 - Once a company with low outside expectations, Surge Energy is now a premier private producer in one of the world’s top shale plays.