Excess natural gas is burned off at an oil well site. (Source: Sean Hannon acritelyphoto/Shutterstock/HartEnergy.com)

Flaring of natural gas, the industry insists, will be resolved when infrastructure projects are completed and producers have access to gathering and transmission pipelines to move gas to market.

But what if gas infrastructure components were already in place? What if an oil producer wanted to flare anyway because economics favored burning it off over paying a midstream operator to take it away?

The Texas Railroad Commission (RRC) is scheduled to address such a case Aug. 6. Exco Operating Co. has requested an exemption to Rule §3.32 of the Texas Administrative Code, which prohibits flaring of associated gas from initial completion beyond 10 producing days. The Williams Cos. has opposed the request, arguing that its Mockingbird Midstream Gas Services LLC system was in operation at Briscoe Ranch in the Eagle Ford when Exco purchased its position.

UPDATE: Texas RRC Sides With Shale Driller In Flaring Vote

Kristi Reeve, an administrative law judge, recommended the exemption be made when she testified to the commission on June 18.

To Gabriel Collins, Baker Botts fellow in energy and environmental regulatory affairs at Rice University’s Baker Institute, the issue pitting midstream giant vs. midsize producer boils down to economics.

“Basically, Exco wants to avoid paying gathering charges on low-priced gas and Williams wants to get throughputs through its infrastructure that it sunk capital into,” he told HartEnergy.com.

Exco had no comment for this article.

Permian's Problems in the Eagle Ford

The irony is that the area where the issue is most pronounced in Texas is the Permian Basin, where a lack of gas infrastructure makes flaring unavoidable without shutting in wells. Setting a precedent in this case concerning an Eagle Ford position could have ramifications as infrastructure projects are completed in the Permian over the next 18 months or so.

“It’s kind of forcing the Railroad Commission to take a position on flaring even though the issues are really different,” said Bernadette Johnson, vice president of market intelligence for Drillinginfo.

“Typically, you flare because you don’t have infrastructure,” Johnson said.

That’s not the case in the Eagle Ford, which has plenty of infrastructure. A contract with Williams for infrastructure near the field was vacated during Exco’s bankruptcy process. The infrastructure remains in place near the field but the valve is turned off.

The two companies are also involved in a related rate discrimination case, the results of which could play a role in the amount of flaring needed should the two companies settle on a rate for Exco’s use of Williams’ nearby pipeline.

But even if the two agree on a rate, Exco would still need to flare for temporary upsets, maintenance and line pressure issues.

Whether Williams’ objection to Exco’s flaring goes away should the pipeline company reach a deal on the rate remains to be seen.

“Exco doesn’t really want to flare the gas. Williams certainly wants to gather it because that’s what they’re in the business of doing,” Johnson said. “If the two of them can agree on a term that allows that to happen, that’s optimal for everybody. I don’t think anybody wants to flare. … Exco is kind of up against the wall."

If Exco can’t agree to a rate in the discrimination rate case and can’t get another gatherer to build infrastructure, then the company can’t produce these wells until it figures out how to handle the gas, she said.

Flaring, Shut-in Options

For Collins, an interesting question is how the RRC defines waste.

“For instance, if you were just looking at the gas molecules, it might look wasteful to flare but if you suddenly looked at the full-cycle economic picture, you realize that by flaring the gas you can actually facilitate greater oil production,” he said.

Exco has said, according to the state, that the only alternative to flaring is shutting in the wells, which produce about 9,000 barrels of oil per day. But everyone seems to agree that could result in damage to the unconventional reservoir.

“That damage could result in a reduction in the total amount of oil ultimately produced from that reservoir,” David Nelson, the attorney representing Exco, told commissioners in June. “That’s what we referred to as physical waste: the waste of that oil reserve. So more than anything we are concerned about that happening in this situation. That is a real problem.”

Johnson told HartEnergy.com that there is risk when shutting in wells. Gas wells tend to come back stronger, she said. But oilier wells, like Exco’s in the liquids-rich part of the play, may not come back as strong.

“If commissioners opt to amend Statewide Rule 32 based on the decision of this hearing and for example explicitly [rule] economic considerations are not viewed as a valid basis for flaring, it could have quite material applications for some E&Ps especially those who are active in very liquids-rich parts of various plays like Eagle Ford and the Permian,” Artem Abramov, head of shale research for Rystad Energy, told HartEnergy.com.

From an economic perspective, it’s more rational to flare gas, he said. “It doesn’t really drive well economics. … Sanchez Energy also flares nearly all of the gas they produce in some adjacent positions to Exco. So, it’s quite common for this area actually not to sell gas but flare.”

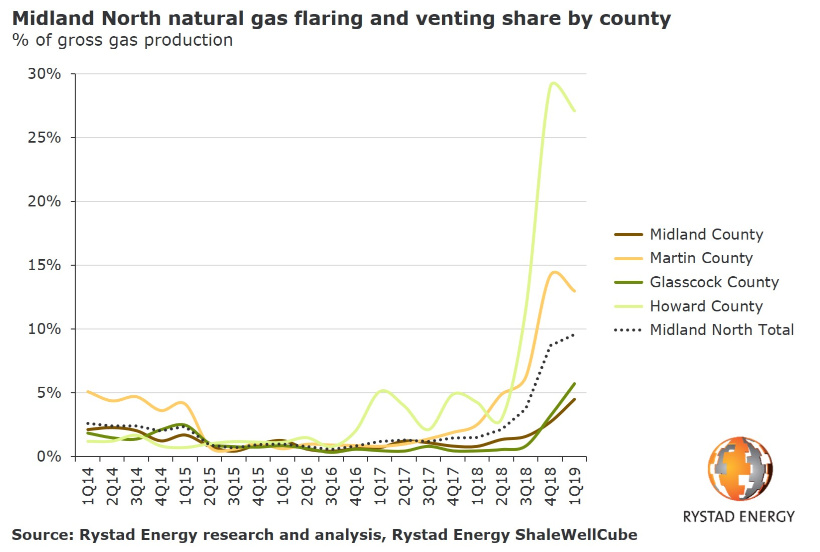

It’s also quite common in the Permian Basin, where Rystad said as much as 661 million cubic feet per day on average was being flared in first-quarter 2019. The estimate was based on data from the RRC and New Mexico Oil Conservation Division and attributed to “persistent infrastructure challenges, a lack of sufficient takeaway capacity and an unexpected outage on a key pipeline in the area.”

Infrastructure is actually overbuilt in some areas in the Eagle Ford, according to Abramov.

Plus, “South Texas is more of a gas play anyway,” added Johnson. “So, unless you’re in the oilier area, like Briscoe Ranch, you need the gas production. It’s a big part of your economics.”

Economics or Waste Rule?

The case represents not only upstream vs. midstream, but also small vs. large. Exco emerged from Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on July 1, having secured $325 million in committed financing. Williams’ market capitalization is about $30 billion.

The Williams gas pipeline is about 6 miles from where Exco is producing in Frio County. The cost to treat and connect its facility to the pipeline is about $7.1 million, according to the RRC docket. Net revenue from the remaining reserves is estimated to be about $1.1 million, however, making it uneconomical to build a pipe connecting the Exco lease to the Williams pipeline.

But even if the economics of transport don’t work, other options may exist for a producer.

“It would be interesting, if you were the judge, to ask the Williams' lawyers how the nature of the claim might or might not be different if Exco, instead of flaring the gas was putting it to some sort of beneficial on-lease use, for instance, enhance oil recovery,” said Collins. “Would they still be bringing the suit? We don’t know what their answer would be. I think it would be very instructive.”

Among those uses, he said, are enhanced oil recovery, electrical generation, small-scale gas-to-liquids and conversion to LNG.

As far as short-term alternatives to flaring, many industry players are already making use of gas. They’re using it to support drilling and completions in the Permian Basin, for example, Abramov said. It’s being used to power surface facilities.

But such uses absorb only a small percentage of gas. If the Permian area was more populated with higher electricity demand, Abramov and Johnson said the gas could be used for electrification purposes at power plants.

Meanwhile, the U.S. market remains oversupplied with cheap gas as the industry awaits clarity on standards in Texas.

Seeking Guidance

“This is an appropriate case for the commission to step back and really carefully think through these issues and what the standard is going to be because it just doesn’t feel right, quite frankly, to have a standard that says anytime there’s an application you get an exception,” John Hays, an attorney for Williams, told commissioners in June. “Then why have the statute in the first place?”

None of the thousands of requests to flare gas brought before RRC have been denied.

“I think this is one in which the regulators want to tread very lightly,” Collins said. “They have to be very careful in how they adjudicate this because one of the things that you don’t want to inadvertently do is turn a gathering contract that’s based on an exclusive acreage dedication into a gathering contract that is, in fact, a take-or-pay agreement, which is not what the parties had contemplated when the original dedication was done.”

Colin Leyden, senior manager for regulatory and legislative affairs for the Environmental Defense Fund, agrees that the issue may come down to the RRC’s definition of waste, which in the past has equated to economic waste when it involves flaring.

“I think that goes directly against what most people would interpret the Railroad Commission’s job is as far as preventing waste and pollution, which is one of their statutory mandates and I would think is one of the objectives of having a flaring rule,” Leyden told HartEnergy.com.

Despite the rising amount of flared gas, particularly in the Permian Basin, Leyden said there are some companies with a “culture of commitment to not flare,” investing in pipeline takeaway capacity, redesigning well pads and using gas on site.

To some extent, Leyden sympathizes with the industry because it needs better regulatory signals when it comes to flaring in Texas in order to make investments.

“Right now, I’ve seen no indication that is likely,” he said. “I think that industry has a self-interest in encouraging the Railroad Commission to take action like that. The companies who are doing the right thing are being punished and the industry as a whole is suffering a reputational risk. … It’s hard to imagine natural gas competing in a low carbon future when West Texas is on fire.”

Leyden said he’d be “pleasantly surprised” if the RRC denied Exco’s request and sided with Williams.

Recommended Reading

Petrobras to Step Up Exploration with $7.5B in Capex, CEO Says

2024-03-26 - Petrobras CEO Jean Paul Prates said the company is considering exploration opportunities from the Equatorial margin of South America to West Africa.

Pitts: Heavyweight Battle Brewing Between US Supermajors in South America

2024-04-09 - Exxon Mobil took the first swing in defense of its right of first refusal for Hess' interest in Guyana's Stabroek Block, but Chevron isn't backing down.

Exxon Versus Chevron: The Fight for Hess’ 30% Guyana Interest

2024-03-04 - Chevron's plan to buy Hess Corp. and assume a 30% foothold in Guyana has been complicated by Exxon Mobil and CNOOC's claims that they have the right of first refusal for the interest.

Rystad: More Deepwater Wells to be Drilled in 2024

2024-02-29 - Upstream majors dive into deeper and frontier waters while exploration budgets for 2024 remain flat.

Exxon Mobil Green-lights $12.7B Whiptail Project Offshore Guyana

2024-04-12 - Exxon Mobil’s sixth development in the Stabroek Block will add 250,000 bbl/d capacity when it starts production in 2027.