You can all go to the Bakken, and I’m going to Texas, David Crockett is said to have declared … or something along those lines.

The frontiersman/legislator made his way in 1835 to East Texas, where a county is now named for him, and later died defending the Alamo against an assault by the Mexican army. Crockett was a romantic—that singular honest politician, natural leader, keen hunter—who was drawn to Texas because it was the frontier.

So 180 years later, his midstream spiritual descendents are launching a peaceful invasion of Mexico via natural gas pipelines, moving hydrocarbons in enormous volumes from fields that weren’t even on a map a few years ago and preparing to ship LNG abroad from 1,000-acre export facilities.

We live in the time of the unconventional oil and gas frontier and—by no coincidence—these trends are Texas-born and reared. No state gets its energy from energy like Texas. Few are considered as friendly toward the industry. And with all due respect to those provinces that host the Marcellus and Utica plays, this is the state of the midstream, y’all.

World-class

“Texas has world-class assets that continue to operate very strongly, even in this price environment and across the hydrocarbon spectrum,” Greg Haas, Houston-based director for Stratas Advisors, a Hart Energy company, told Midstream Business. “Natural gas, NGL, condensates, crude oil—all these are predominantly light liquids or gas coming out of Texas, and as such, the state will hopefully find some markets for that rush of hydrocarbons to our shores along the Gulf Coast.”

Getting to those markets, whether in the interior of the U.S., in the refining and petrochemical empire along the Gulf Coast or to customers in other countries, defines success. Demand has slackened during this downcycle, but there are hints of when a recovery can be expected and preparations underway for when it arrives.

“The midstream really has been very important in connecting the dots,” Gürcan Gülen, senior energy economist at the Bureau of Economic Geology’s Center for Energy Economics at the University of Texas at Austin, told Midstream Business. “They’ve been building a lot of pipelines, a lot of processing, condensate splitters, whatever the industry needs to get the products to the market.

“In many cases, all roads lead to the Gulf, in particular the Houston Ship Channel area,” he continued. “In the case of a lot of the liquids—ethane, propane, butane—the Gulf is where we have a lot of storage capacity, that’s where we have the pricing points, users and export facilities.”

Distorted view

“In 2005, the EIA [U.S. Energy Information Administration] came out with a report saying that by 2015, the U.S. would be importing 3 trillion cubic feet [Tcf] per year of LNG,” said Christopher Click, Dallas-based principal with KPMG LLP, at a recent briefing for Houston energy journalists. “That 2005 report turned out to be wrong. Now we’re actually constructing 3 Tcf of LNG export capacity. The shale development in North America fundamentally shifted trade flows across the globe.”

Logically, the impact from such an epic shift will be felt both internally and externally. The internal reaction was the realization that a massive investment, estimated at around $900 billion, was needed to build the infrastructure that would move the commodities from areas of production to demand centers over the next several decades.

“Interestingly, what we’re seeing more recently is that $900 billion in midstream investment can be a little elusive,” Click said. “When you start to dig into it from a certain company’s perspective, it’s not exactly $900 billion in the sectors you’re most interested in or that you can compete in and in the current climate. Some of that’s maybe pushed out a bit.”

That’s because a funny thing happened on the way to the bank to cash that $900 billion check: the external reaction kicked in.

The complex boom

“There is an infrastructure boom,” Click said. “There is an American renaissance, but it’s a little bit more of a complex story than I think folks originally thought even earlier on this year.”

KPMG’s energy team has been monitoring the production gambit launched by OPEC and led by Saudi Arabia. The rapidly falling price of crude oil has definitely influenced forward progress in the North American shale plays, but perhaps not in the way expected.

“It’s one thing to pursue a market-share war when the market is extremely consolidated and there are just a few key competitors,” Click said. “Signaling works and you can expect rapid responses on the part of your competitors. It’s not always the best idea to pursue a market share-war against a sector like the U.S. E&P sector that is so fragmented. There are actually a very large number of decision makers who are making day-to-day investment decisions. They don’t pick up on your signals or necessarily have the same motivation to respond to your signals that more consolidated markets do.”

The result is a round of greater efficiencies and, earlier in the year, increased production despite a sharp reduction in the U.S. rig count. Hence, the V-shaped recovery than many expected didn’t happen, Click said, and the markets have been gripped by a price volatility that doesn’t appear to be willing to loosen any time soon.

“It’s such a fragmented set of players [in North America] and their decisions are so different,” added Regina Mayor, KPMG’s national sector leader for its energy and natural resources practice. “Some are hedged and they can keep going until 2016. For others, it’s still marginal production, shut-in wells that have started and they’re not going to turn anything off. Others are making a play for a rebound. There are completely different mindsets, and I think it’s befuddled the OPEC leadership.”

OPEC’s mindset revolves around the concept of a national oil company that follows the policies of a national government. The U.S. energy sector is a capitalistic scrum constantly striving to get products to customers as efficiently as possible. Not only do these opposing forces not see eye-to-eye, they may not see each other at all.

“How quickly the U.S. made itself more competitive, how rapidly the producers went and grabbed cost savings from the supplier base, how quickly they were able to idle rigs and shut down contractor temporary work forces is to me, capitalism at its best,” observed Angie Gildea, KPMG principal. “I think sometimes the rest of the world gets surprised by that.”

What drives producers

Click sees a number of economic and behavioral factors that drive U.S. producers. Among them is the fact that many already have hedges in place and won’t change their strategy because today’s oil price is down. Companies also know that there is plenty of capital, including that provided by private equity players, ready to go to work in the sector. And so far, banks are in no rush to put on the brakes, especially when portfolios are still relatively healthy.

Then there is the mentality of some in the E&P crowd, determined to deliver quarter-on-quarter production growth to propel the stock price.

“There is a belief that we have to grow production or find ourselves trapped in the E&P death spiral,” Click said. “Cut capex, production goes down, which means you have less cash flow, which means you have to cut capex, which means production goes down, which means your bank is eventually going to reset your borrowing base.”

That’s changing, Mayor said, but slowly.

“The biggest mindset in upstream—and even though they’ve been talking about changing this for three to five years, I’ve only now seen them start to try changing it—has always been about time to first oil and optimizing drilling,” she said. “‘I care about how quickly I can drill but my rig might be costing me $1 million a day and that’s the only cost I’m going to manage. That’s the only thing I look at: time to first oil.’ Now they’re actually sitting back and saying, ‘Why is that supply boat going back empty? Why am I agreeing to let XYZ oil-field services company charge me cost plus X%?’”

Selling to OPEC?

Like a giant magnet, the refining/petrochemical complex of southeast Texas draws a rush of hydrocarbons to America’s third coast. Where will it go? Would you believe to a member of OPEC?

Earlier this year, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) put out a tender to purchase 70,000 barrels per day (bbl/d) of stabilized condensate, the ultralight oil. Venezuela, like Canada, Mexico, Ecuador and Russia, produces heavy crude oil. Typically, producers of heavy crude use naphtha as a diluent, but stabilized condensate is cheaper at the moment, particularly with Iran preparing to release 60 million bbl onto the market.

“I wouldn’t doubt if some of the U.S. condensates that have been stabilized for export ultimately get consumed and used in Venezuelan crude,” said Haas.

The U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) determined last year that using a stabilizer to split field condensate into NGL, dry gas and stabilized condensate creates what qualifies as a refined product, making it eligible for export.

“These kinds of new processing equipment are coming to Texas in greater count,” he said. “That’s more than likely going to expand. Once it gets stabilized in the field, you need separated condensate pipelines to keep this segmented from the unstabilized condensate. If you build those pipelines, then you have to get it to the coast, then you’ve got to have condensate storage that’s fit for stabilized condensate and segmented from other liquids. If you have that, then you can put it on a tanker and ship it to points all over the globe.”

Asian markets are a possibility, Haas said, but geographical proximity makes the Americas a better bet.

“The shipping cost will be far lower to say, Venezuela, then it would be through the Panama Canal or around South America and up to Asia from Texas,” he said. “My sense is, the Americas will be the market par excellence for Texas-based condensates.”

Haas believes that Texas naphtha exports are more likely to stay in the hemisphere and be purchased for use in South American petrochemical manufacturing. There are some buyers for U.S. naphtha in Asia, but they can likely find cheaper sources in the Middle East.

Still growing

Even in a land of sunny optimism like Texas, spirits have fallen with oil prices. But midstream projects, in spite of the gloomy forecast, continue to move forward, positioning the state for the rebound to come.

The Seaway Twin Pipeline, a joint venture of Enterprise Products Partners LP and Enbridge Inc. that moves Canadian crude to the Gulf Coast, is primed for an increase in capacity from 450 Mbbl/d to 650 Mbbl/d. Plains All American Pipeline LP is building the 80-mile, 12-inch Caddo Pipeline to pump up to 80 Mbbl/d from Longview, Texas, to refineries in Shreveport, La., that should be complete by mid-2016.

Depressed commodity prices convinced Phillips 66 to delay construction of its Sweeny, Texas, condensate splitter to late 2016, but Phillips has a new lead shareholder in Berkshire Hathaway Inc., the multinational holding company run by Warren Buffett. The $4.5 billion investment in Houston-based Phillips, giving Berkshire a 10% stake in the company, signals renewed confidence that energy is an industry in which to make money.

And in the storage arena, Trans Canada announced plans for a 700,000-barrel terminal that will be an addition to its Gulf Coast Project. Fairway Energy Partners LLC announced plans to build the Pierce Junction Crude Oil Storage facility at a salt dome in south Houston. The project will have a capacity of about 10 million barrels, with expansion of up to 20 million barrels. It will include construction of two bidirectional, 24-inch pipelines to connect the facility to the area’s crude oil grid.

“PADD 3 [Gulf Coast] has about 325 million bbl of crude oil storage capacity,” said Haas. “If you’re adding 20 million in the city of Houston alone, that’s a significant increase.”

Future bound

David Crockett may have lost his last bid for reelection to the U.S. House of Representatives, but Washington was no longer his land of opportunity. Texas was.

For the energy industry, it still is. The geologic blessings of the Permian, Panhandle, Eagle Ford, Barnett, Haynesville and other formations would be little more than subterranean potential were it not for the will of the people of this state to convert it to energy. That will has fostered construction of 432,000 miles of pipeline—so far—to monetize those molecules. Even in an industry downturn, output from Texas overwhelms that of most countries during a boom.

Haas sees several opportunities carrying the state into the future:

• Continued strong production of oil and gas;

• Continued strong investment in pipelines getting this production to the Gulf Coast;

• Some growth in consumption in Texas and on the Gulf Coast, especially in the chemical plant sector; and

• Ultimately, exports either to Canada and Mexico, or to points far offshore.

“The great bounty of Texas hydrocarbon production has certainly reached the Gulf Coast,” he said. “It’s causing new investment in pipes, storage and processing facilities and chemical plants on the U.S. mainland, but it’s also instilling opportunities to export that around the world.”

Crockett would be proud.

Like A Good Neighbor, Texas Is There For Mexico’s Natural Gas Needs

To start, the Mexican energy market “has some quirks,” veteran energy journalist Housley Carr wrote in a recent piece for RBN Energy. These stem from the prereform regulatory environment of a market in transition.

In January 2016, the Mexican national energy company, Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) begins to lose its exclusive role as the only legal importer of LPG. By January 2017, the Mexican government will no longer have a role in setting retail prices for LPG. That means market-based pricing that reflects supply, demand and the variable cost of distribution depending on location, Carr wrote.

That means opportunity for U.S. exporters. San Antonio-based NuStar Energy LP has joined with Pemex affiliate PMI in a joint venture (JV) to develop a pipeline system to move LPG and refined products from Mont Belvieu and Corpus Christi, Texas, to Nuevo Laredo and Burgos-Reynosa in northern Mexico. The two had already partnered to ship propane to Mexico. The projects are expected to be in service by second-half 2016.

“Mexico typically needs propane for all manner of uses—cooking, heating, maybe even power generation and some chem plants,” Greg Haas, Houston-based director for Stratas Advisors, a Hart Energy company, told Midstream Business. “NuStar wants to move LPG from Corpus Christi across the Mexican border via pipeline, so no tankers required. That’s sort of an interesting new wrinkle, but it’s all about getting purity NGL from the fractionators in Texas to viable and vibrant markets including Mexico.”

It’s the prospect of natural gas exports to Mexico that feeds optimism among midstream players.

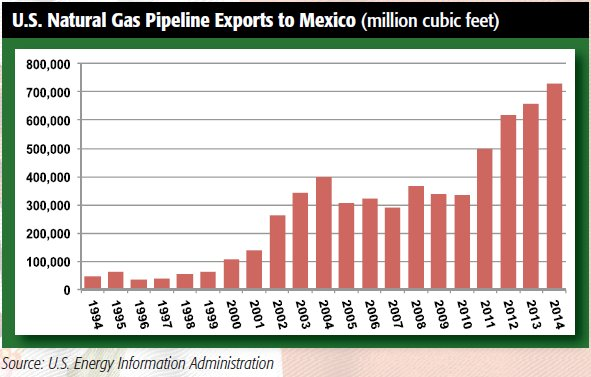

U.S. exports to Mexico doubled between 2009 and 2013, and America’s Natural Gas Alliance (ANGA) sees the border as a breeding ground for pipeline construction, including projects by Energy Transfer Partners, Sempra Energy, Kinder Morgan and Howard Midstream Energy Partners LLC’s Nueva Era pipeline, which the San Antonio-based company is building with JV partner Grupo CLISA. The 200-mile, 30-inch pipe will have a capacity of 504 million cubic feet per day (MMcf/d) and connect Howard’s Webb County hub in South Texas to Escobedo, Nuevo León, and to Mexico’s national pipeline system in Monterrey. Howard already has approval from the U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to expand Nueva Era’s capacity to 1.2 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d).

“It’s a great opportunity for Texas,” Erica Bowman, ANGA’s vice president of research and policy analysis, as well as chief economist, told Midstream Business. “Not only is there economic growth opportunity at the border where pipelines are being built, but the U.S. is also producing the gas that’s being delivered to Mexico.

For every 1 Bcf/d that is produced incrementally, 15,000 upstream jobs are created. Texas being the supplier to Mexico is really a great opportunity for the natural gas industry in Texas.”

There are plenty of sources for natural gas in the state to feed the Mexican market. Eagle Ford in South Texas is best-positioned geographically, but gas can also be expected to flow from the Haynesville Shale, associated gas from the Permian Basin, and shale plays in surrounding states like Oklahoma and New Mexico. The Mexico dynamic influences the flow picture across the U.S.

“Now, you also see natural gas produced in the northeast heading in the opposite direction,” Bowman said. “You’ve seen a lot of bi-directional pipelines moving production from the Marcellus and Utica down to the southeast, often moving production from the northeast over to the west. But some of that ability for the northeast-produced gas to move in that direction is created by the fact that gas being produced in Texas and in the southeast is moving to Mexico.”

Not that Mexico does not possess plenty of its own gas reserves. The Central Inteligence Agency’s World Factbook estimates reserves of 483.5 trillion cubic feet and annual production in 2013 of 46.43 Bcf. Demand, however, outpaces what the country can produce, at least in the short run. Mexico’s Ministry of Energy estimates a total demand increase for natural gas of 38.3% between 2006 and 2016, with power generation demand rising by 61.2%, or an average of 5.1% per year.

“In Mexico’s current situation, they’ve experienced an incredible amount of growth domestically with respect to their manufacturing sector, and they’re really looking to natural gas as their fuel of choice,” Bowman said. “Mexico’s own natural gas and oil production has been on the decline.”

Mexico’s own quest for increased domestic production will take at least a decade, Gürcan Gülen, senior energy economist at the Bureau of Economic Geology’s Center for Energy Economics at the University of Texas at Austin, told Midstream Business. “It’s going to take time for them to have successful bidding rounds and attract new investment and drill enough wells and put the infrastructure in place to gather the gas from the producing fields,” he said. “In the meantime, they’re going to need gas from the U.S., which looks like it’s going to be cheaper than the LNG that they have been importing.”

And why not rely on a good neighbor?

“Our advantages in the U.S. are so strong,” Haas said. “We have great oil service, we have great resources such that it may be decades before they expand their service industry enough—even if they had the resources, which I’m not sure they do in certain areas—it may be decades to catch up with what we already have in the Eagle Ford and the Permian.”

What If The Ban Were Banned?

The premise seems simple: U.S. shale plays have been wildly successful, producing more light oil than the country needs. A law dating to 1975 restricts exports of U.S.-produced crude except in certain circumstances.

So, change the law to reinforce the concept of free markets, reactivate those idle rigs and return production to previous glory, then watch the tankers sail away and the price of West Texas Intermediate rise simultaneously.

Texas, with its hard-charging Eagle Ford and Permian Basin shale plays, and the Houston Ship Channel that first engaged in the oil trade in 1914, would appear to be particularly well-positioned to benefit from a lifting of the ban.

Assuming, of course, that the oil has somewhere to go. U.S. producers would need to find a market where the light, tight oil from North American shale plays is needed, and global trade flows have experienced a shift as a result of the very same boom in North American oil production.

“If you look what has happened on the crude oil market since the U.S. tight oil boom started, you would see a reduction of African [Nigerian, Algerian] crude imports to the U.S.,” Dr. Petr Steiner, Brussels-based director and expert on global refining for Stratas Advisors, a Hart Energy company, told Midstream Business. “That crude needs to find a home.”

Some of it found a home in Asia, mainly India, Steiner said, with other output finding its way to Indonesia. However, very little African light oil entered the Chinese market. China continues to rely on producers in the Middle East and Russia/Kazakhstan for its crude.

What Steiner found notable was that African crude, replaced in the U.S. market by domestic production, ended up filling the gap in Europe created by declining North Sea light oil production.

“If I were to project where U.S. crude could find a market, I would think northwest Europe,” Steiner said. “I know Europe would like that—avoid heavy crudes [for example, imports from Canada or Venezuela] to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The question is: what would it mean for U.S. and global markets?”

Many U.S. refineries were reconfigured prior to the shale boom to handle imported heavy crudes from Venezuela and Mexico. A recent decision by the U.S. Department of Commerce allowed crude oil swaps with Mexico—exports of U.S. light in exchange for imports of Mexican heavier grades.

Though that decision lifted the spirits of many who desire a lifting of the total ban, it was more likely a move to avoid any challenge under the North American Free Trade Agreement, John Kneiss, Washington-based director for Stratas, told Midstream Business.

“I do not view this decision by the Obama administration as movement toward a ‘lifting’ of the export ban—rather a pragmatic move as a ‘safety valve’ release of pressure,” he said. “Lifting the ban entirely would take an act of Congress.”

So what happens if the ban is lifted and light oil is exported? Presumably, heavier crudes would need to be imported to meet demand. Steiner speculated that Venezuelan heavy crude exported to Asia would be diverted to the closer U.S. market. Presumably, Middle Eastern suppliers would fill the gap in Asia.

Geopolitics sways markets as well, Steiner noted.

“If the U.S. waits too long, Iran will return to the market in early 2016, and there will scarcely be a place to put extra crude exported from the U.S.,” he said.

But is it even necessary to lift the ban on U.S. crude oil exports? From a philosophical point of view, many agree that it is. Whether it is needed in a practical sense is a different matter.

“As an economist I have to say that there is no need to have a ban, and that we should let the markets work,” Gürcan Gülen, senior energy economist at the Bureau of Economic Geology’s Center for Energy Economics at the University of Texas at Austin, told Midstream Business. “Having said that, in this particular situation, I think so far the industry has been able to export a lot of the products that they wanted to export.”

The U.S. has evolved into a significant net exporter of LPG over the past five years, he said. Now, processed condensate, allowed to be exported through a Department of Commerce decision last year, has averaged shipments of 84,000 barrels per day through the first five months of 2015, the U.S. Energy Information Administration reports.

“I think [lifting the export ban] would prop up crude prices some, but is it necessary? I don’t think it is necessary,” Greg Haas, Houston-based director for Stratas, told Midstream Business. “Some producers with high costs or producers in remote locations like the Bakken or Niobrara would certainly like to see prices go up and the way to do that would be to allow crude exports to happen, but I’m not so sure it needs to happen.”

Texas, Haas said, is fine without.

“I think Texas especially is blessed with proximity to the coast and proximity to major refining markets and processing and fractionation, and we share a border with Mexico,” he said. “I’m not sure we need to have crude oil exports.”

Recommended Reading

US Drillers Add Oil, Gas Rigs for First Time in Five Weeks

2024-04-19 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, rose by two to 619 in the week to April 19.

Strike Energy Updates 3D Seismic Acquisition in Perth Basin

2024-04-19 - Strike Energy completed its 3D seismic acquisition of Ocean Hill on schedule and under budget, the company said.

Santos’ Pikka Phase 1 in Alaska to Deliver First Oil by 2026

2024-04-18 - Australia's Santos expects first oil to flow from the 80,000 bbl/d Pikka Phase 1 project in Alaska by 2026, diversifying Santos' portfolio and reducing geographic concentration risk.

Iraq to Seek Bids for Oil, Gas Contracts April 27

2024-04-18 - Iraq will auction 30 new oil and gas projects in two licensing rounds distributed across the country.

Vår Energi Hits Oil with Ringhorne North

2024-04-17 - Vår Energi’s North Sea discovery de-risks drilling prospects in the area and could be tied back to Balder area infrastructure.