Casper, Wyo.—1,094 miles from Seattle, 4,766 miles from Paris and 1,867 miles from the reigning hipster capital of Hoboken, N.J.—is the trendy place to be, at least in the realm of hauling crude oil by rail.

This designation isn’t based on the city’s selection of microbreweries (just one) or venues for foreign films (none, apparently). Casper’s trendiness involves parking a rail terminal near a major pipeline, in this case Spectra Energy Partners LP’s Express Pipeline that pumps Canadian crude from Hardisty, Alberta.

Casper Crude to Rail LLC offered an initial capacity of 72,000 barrels per day (bbl/d) when it went into service in September 2014. The project, a joint development of Cogent Energy Services, Granite Peak Development and Stone Peak Infrastructure, quickly ramped up to 100,000 bbl/d and boasts a maximum build-out capacity of 288,000 bbl/d. It includes a six-mile, 24-inch pipeline that connects to the Express.

The original cost of the plant was around $60 million, although the expense of subsequent upgrades is not known. What is known is that in October, just 13 months after in-service, Houston-based USD Partners LP bought the property for a total of $225 million in cash and limited partner units.

Who cares if Casper didn’t make the cut for U2’s latest concert tour? This city’s hipness is confirmed by its own rail terminal-fostered real estate bubble.

All about optionality

“Canadian crude crosses the border in an existing pipeline, gets all the way to Wyoming and can be loaded onto unit rail trains,” Greg Haas, Houston-based director for Stratas Advisors, told Midstream Business. “Or, it can connect into other pipelines. More Canadian crude can thereby go further into the U.S. Midwest, East Coast, West Coast for heavy-capable California refineries, or certainly to the Gulf Coast, where so many refineries are geared for heavy Canadian crudes.”

The breadth of options offered at a strategically located facility provides relief to an industry grappling with a dicey price environment. Rail’s optionality keeps it viable despite expectations that pipelines would be well on their way to leaving it behind.

“By integrating pipeline and crude-by-rail (CBR) logistics, you meet halfway in the middle of the nation and then you have optionality instead of requiring a pipeline to go straight from Alberta to the Gulf Coast,” Haas said. “The optionality of crude by rail, once you get across the border by pipe, is a very nice feature for current conditions.”

And the economics are improving, as well. Early in the fourth quarter, Reuters reported that the principal Canadian crude-by-rail movers, Canadian National Railway and Canadian Pacific Railway, were offering discounts of as much as 25% to hold onto market share in the face of diminished crude production and shipping.

Commodity news tracker Genscape reported in November monthly tank car lease rates had fallen to $475 per month from $2,000 per month in early 2014 as demand has softened.

Energy economics

The Canadian railways are not alone in reinforcing the idea of optionality in customers’ minds to keep their edge.

“The crude market can be very unpredictable, but moving shipments via BNSF’s crude oil train network enables our customers to respond to those changes by moving their products where they will get the best price at any given time in the market place,” Teresa Perkins, BNSF Railway’s assistant vice president, petroleum, industrial products, told Midstream Business. “This provides customers utilizing trains to move their crude an advantage over traditional means of crude transportation.”

For the railways, it’s a matter of adapting to a changing energy environment. Their solid business of delivering coal is slipping as natural gas takes its place in power generation. But it’s not just energy. General economic stagnation means that goods used in construction—like timber, gypsum, steel and copper—also are moving less often.

Those products will return to the rails when the economy improves, but coal is on its way out and its replacement in power generation, gas, will not replace it on the trains.

“We keep continuing to hear that drumbeat. Economically, gas is very, very cheap today,” Haas said. “Operating a gas-fired power plant and building a gas-fired power plant costs far less than building or operating a coal plant, especially if you consider that these are long-lived assets and, as such, the scenario planning for investment certainly has to incorporate some consideration for carbon emissions. With politics and regulatory requirements, the lower-carbon fuels like natural gas will tend to become a greater, more economic or less-taxed source of energy for our continent.”

Changing minds

But if rail companies are bedeviled by this tectonic shift away from coal, and current low prices mean less crude to carry, they also benefit from the industry’s newfound realization that rail is indispensable simply because it can do things that pipelines cannot.

“Rail has its place,” said Richard Kinder, executive chairman of Kinder Morgan Inc., at the CERAWeek conference in Houston earlier in 2015. “I used to not think that as a pipeliner. I thought, well, rail is an interim step and as soon as you can pipe something up, rail goes away.”

Kinder, whose company operates more than 80,000 miles of pipe, hasn’t exactly turned his back on that mode, and insisted that pipelines are the safest and cheapest way to move hydrocarbons. But rail’s optionality, its ability to quickly move product to a different market depending on arbitrage, makes customers happy. To keep them happy, Kinder Morgan opened its 250,000 bbl/d-capacity Edmonton Rail Terminal in Alberta, a 50:50 joint venture with Imperial Oil Co., earlier this year.

In the third quarter, the company also commissioned its new $34 million CBR destination terminal at its Deer Park Rail Terminal on the Houston Ship Channel. The unit train facility is capable of unloading one train per day of a wide range of heavy and light crude oil grades.

“I think you’re going to see, both on the supply side and the demand side, a preference for having part of the supply move out by rail,” he said. “With rail, you don’t have to make as long a commitment and you have more optionality to take into account the volatility of pricing. If one day you want to move it to Baton Rouge and the next day to L.A. [to capture arbitrage], you can do that.”

The big ‘if’

The evolution of the shale boom can be seen very clearly in the Bakken. First, there was no infrastructure, so associated gas had to be flared and crude trucked and moved by rail. Then pipelines were built, lessening the need for trucks and trains.

Well, actually, pipelines were planned and pipeline companies forced to engage in complicated and increasingly prolonged efforts to secure permits, so the need for CBR is not reduced as much as presumed.

“Right now, there’s 500,000 bbl/d of Bakken crude moving by rail,” said Nicole Leonard, project manager for Bentek Energy, at a recent Platts conference in Houston. “That’s expensive. And that’s why you see such steep differentials in the Bakken. You have ETP [Energy Transfer Partners LP] in the Bakken, hopefully relieving some of the constraints, hopefully relieving the differentials. Then you also have Sandpiper and Upland [pipeline projects]. If those two projects come online, there will be plenty of infrastructure to facilitate this growth in production.”

“If” is a pretty big word in that sentence. Enbridge’s Sandpiper Pipeline would tie into its system that is already struggling with bottlenecks. Minnesota’s Public Utilities Commission recently suspended a key permit for Sandpiper after a court ruled that the commission needed to conduct an environmental impact statement. TransCanada’s Upland project would connect to that company’s Energy East pipeline, which has been stymied by environmentalist pushback.

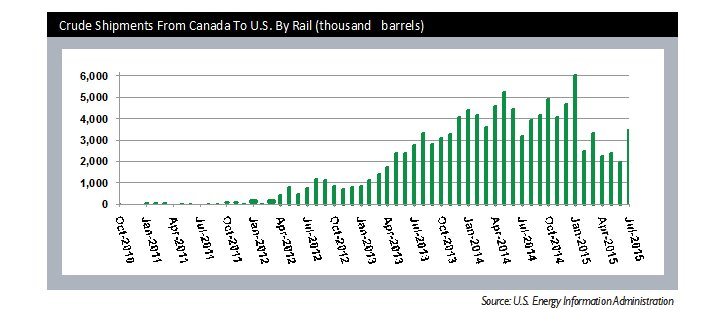

The outlook for northern pipelines teeters between extremes. Push through the four major projects—Enbridge’s Northern Gateway, TransCanada’s Energy East and Keystone XL and Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain—and Western Canada is overbuilt, with far more capacity than it is able to use. Given the resistance from environmental organizations and the recent Keystone XL permit denial, Leonard expects the status quo to remain in effect, which means rail will have a larger role in moving crude out of Canada.

“This decade, there’s a good chance we won’t see any of them,” she said.

Haas is skeptical as well.

“If some high-volume capacity pipelines were to be installed out of Alberta incrementally—Energy East, Northern Gateway or TransCanada’s [Keystone] XL or anything else that might come along, I would think that would tend to depress crude by rail loadings in Canada,” he said. “But those are some big ‘ifs’, hotly opposed in many parts of Canada and the U.S. as well.”

Assuming the midstream doesn’t see those pipelines, then it will see unit trains. Long ones. BNSF is keeping up with that rapid growth by investing $3.5 billion in its Northern Corridor route since 2013 to maintain and improve line capacity, Perkins said. That is part of the more than $50 billion that the railroad has poured into its total network since 2000.

“BNSF expects to continue playing an important role in helping the U.S. and North America replace imported crude oil with that being produced from the continent’s vast oil reserves,” she added. “Modern day U.S. oil production has resulted in the market seeking transportation alternatives to move oil to destination markets. BNSF will continue to fill the gap in crude oil transport capacity, providing an innovative and reliable solution through unit trains well into the future.”

Adding sand

Haas has tracked the maturation of CBR for several years, beginning with manifest loading where a few cars loaded with crude would be attached to a general merchandise train that just happened to be going in the right direction (he likens it to hitchhiking.) It worked pretty well when the price differential between the Bakken Shale play in North Dakota and the Gulf Coast refining complex was between $20 and $30 per barrel. Now that divide is in the $4 to $5 range.

“If you’re looking to invest in crude by rail, you have to make it unit train, and you better think about doing something other than just crude,” he said. “If you can handle oil service goods—frac sand especially—as well as crude by rail at your terminal, you might still have a good shot at making strong economic returns, even today with crude oil prices very low.”

The employment of long unit trains and cross-commodity hauling are two of the significant trends in the sector, trends that Sugar Land, Texas-based Rangeland Energy has embraced whole-heartedly. The company’s president and CEO, Christopher W. Keene, described completion rigs—not every area is going to be strong, but what is strong is for the areas that are still completing and fracking wells, the wells are typically getting longer which means you want to have more sand per well.”

The completion stage is a complementary one: bringing more sand in means pumping more crude oil out. Those kinds of volumes could lend themselves to opportunity, he said.

“If a sand terminal and an oil terminal can coexist, it could be an interesting new way to make the economics work, even in a $3 and $4 differential world.”

Recommended Reading

NOD Approves Start-up for Aker BP’s Hanz Project

2024-02-27 - Aker BP expects production on the North Sea subsea tieback to begin production during the first quarter.

E&P Highlights: March 15, 2024

2024-03-15 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including a new discovery and offshore contract awards.

E&P Highlights: March 4, 2024

2024-03-04 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including a reserves update and new contract awards.

OKEA Fast-tracking North Sea’s Brasse Tieback to Brage

2024-04-08 - OKEA expects first production in 2027 and has signed contracts with Aker Solutions, Subsea7 and OneSubsea.

E&P Highlights: April 8, 2024

2024-04-08 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including new contract awards and a product launch.