The total number of SPAC IPOs jumped to a record of 45 in 2018—the highest number since 2007—with several of these SPACs focused on the energy industry. (Source: Hart Energy/Shutterstock.com)

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the August 2019 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

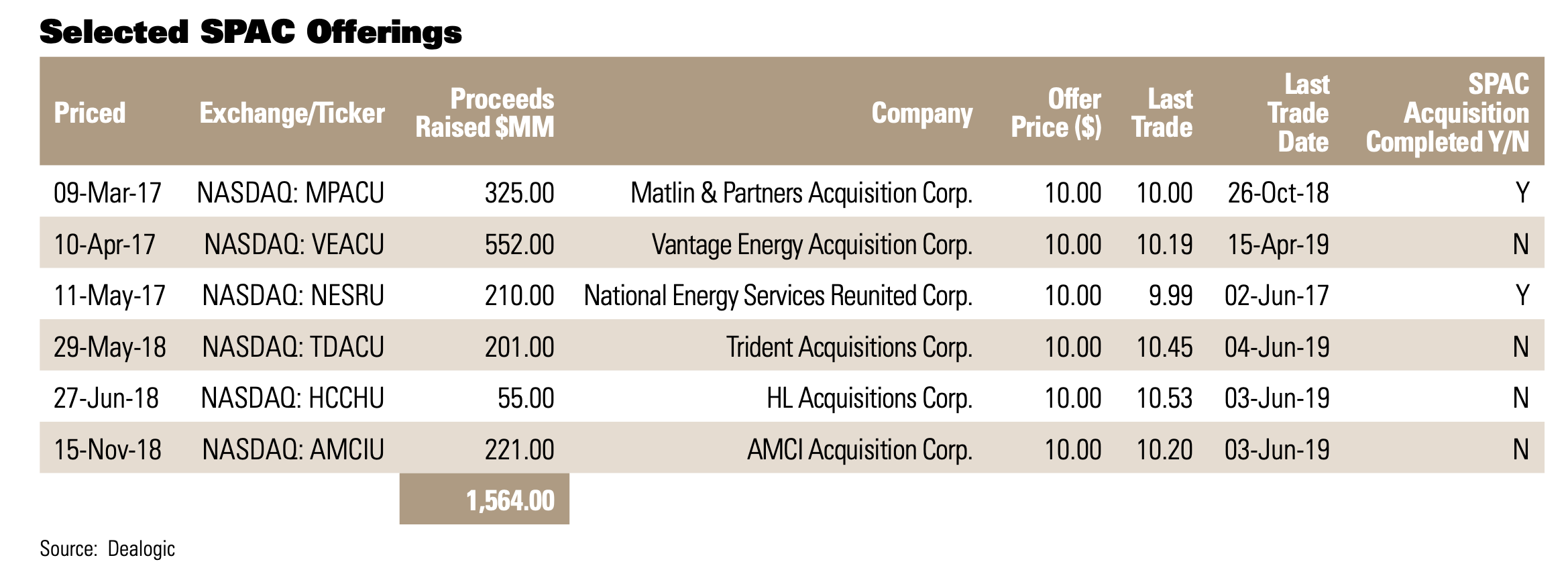

In the past three years, special purpose acquisition companies, or SPACs, have enjoyed a surge in popularity, with a noticeably large proportion targeting the exploration and production, midstream and oilfield service sectors. Though several of these energy-focused SPACs have announced or closed transactions, at the time of this writing, we count 10 energy-focused SPACs with around $2.6 billion in available capital that are still seeking a transaction.

The SPAC structure is popular, but it presents challenges to sellers when they transact with a SPAC. There are several reasons why SPACs have had an increasingly difficult time finding a transaction in the last six months.

What Is A SPAC?

SPACs are formed and supported by a sponsor, typically consisting of a private-equity firm or other institutional investor who usually recruits a management team composed of well-known executives with experience managing large companies in the SPAC’s area of focus. For example, private-equity firms Riverstone Holdings, NGP Energy Capital, Kayne Anderson Capital Advisors LP, TPG Global LLC and Apollo Global Management LLC have each sponsored SPACs. A SPAC completes its IPO on the strength of its sponsor and management team. It then seeks a business opportunity using its IPO proceeds and its publicly traded stock as transaction consideration.

In its IPO, a SPAC typically will issue units to the public for $10 each, which units consist of one share of common stock and one-third or one-half of a warrant to purchase one share of common stock at $11.50 per whole warrant. Shortly after the IPO, the warrants can be traded independently from the common stock. Along with the units issued to the public in the IPO, SPACs usually also issue “founder shares” to the sponsor and to certain members of the SPAC’s management team. The founder shares are a separate class of stock from the class issued to the public in the IPO and usually convert automatically into a significant percentage of the publicly held class of outstanding common stock of the SPAC when the SPAC closes its first acquisition.

Because the investment is purely speculative at the time of the IPO, SPAC stockholders have a number of protections that help to hedge their investment risk. A SPAC generally has only two years following its IPO to close its first acquisition before the SPAC expires. During that time, the IPO proceeds are held in trust. The IPO proceeds are only released from trust in connection with the closing of the SPAC’s first acquisition, provided that the closing occurs prior to the SPAC’s expiration or, absent such an acquisition, in connection with the SPAC’s redemption of its public stockholders for cash at the SPAC’s expiration.

In connection with the SPAC’s first acquisition, SPAC stockholders have the right to compel the SPAC to redeem their common stock for their proportion of the IPO proceeds held in trust. Additionally, stockholders generally have the right to approve or reject the acquisition.

SPAC stockholders are not required to vote against the acquisition to redeem their common stock, and they are entitled to keep the SPAC warrants they received in the IPO regardless of their vote and regardless of whether they compel the SPAC to redeem their common stock. Accordingly, SPAC stockholders are able to shed almost all of the potential downside of the post-acquisition business while still retaining a portion of the potential upside. These stockholder protections make transactions with a SPAC uniquely challenging from a seller’s perspective, as discussed in greater detail below.

Recent Surge in SPACs

In 2017, there were a total of 32 SPAC IPOs, with that number jumping to a record of 45 in 2018, the highest number since 2007. Several of these SPACs are focused on the energy industry.

The rise in the number of energy-focused SPAC IPOs coincides with a sharp decline since 2014 in the number and dollar size of traditional IPOs of energy companies. In 2014, 29 energy-focused IPOs closed, raising an aggregate of $11.6 billion. Since the oil price downturn in 2014, capital markets have generally been less receptive to energy companies, particularly those attempting an IPO. As a result, there have been only 35 energy company IPOs, raising an aggregate of $11.7 billion, in the four full years since 2014. With public capital markets generally unavailable to private energy companies, these companies, many of which are backed by significant private-equity investment, must find other avenues to monetize their investments. SPACs have stepped into this void in significant numbers.

SPACs present an attractive counterparty for a private energy company because they have both available cash and a public-equity currency. Additionally, the SPAC’s sponsor is incentivized to consummate an acquisition in order to create value in its “founder shares.” This creates ability and motive for the SPAC to transact at higher valuations that are difficult to match for other prospective buyers. For many potential sellers, these high valuations have outweighed the challenges associated with a SPAC transaction.

SPAC Transactions

SPAC stockholder protections present challenges when transacting with a SPAC that differ from those of a typical merger or acquisition.

As mentioned, SPAC stockholders are entitled to redeem their common stock in connection with the SPAC’s first acquisition. To facilitate this, the SPAC is required to prepare and file a lengthy public disclosure document that complies with Securities and Exchange Commission disclosure requirements and the terms of the SPAC’s organizational documents. These filings are labor-intensive, time-consuming and expensive to prepare.

Although a reduced price

is not desirable for the seller, the

seller will have spent significant time

negotiating the terms of the transaction

with the SPAC and may feel compelled

to continue with the SPAC.

If SPAC stockholders redeem their common stock, the amount of cash available for distribution to the seller will be reduced. SPAC stockholders are not required to make their redemption election until very near closing of the SPAC transaction.

The potential for redemptions and the uncertainty about the amount of redemptions puts the SPAC as the buyer and the seller in a position where they end up negotiating deal terms with incomplete information. Excessive redemptions can result in the transaction failing to close, or the seller agreeing to replace a portion of its cash consideration with SPAC equity consideration to achieve a closing. The specter of excessive redemptions also presents the SPAC with an opportunity to renegotiate the transaction price with the seller even after the SPAC and the seller have signed a definitive agreement.

Because the SPAC IPO proceeds are held in trust, break-up fees are not available to compensate the seller for transaction risk and the cost of the seller’s lost opportunities. A seller can negotiate for the sponsor to make up some of the cash shortfall created by redemptions, but a sponsor backstop is often an incomplete solution in the face of overwhelming redemptions.

Depending on the size of the transaction relative to the amount of the SPAC’s IPO proceeds held in trust, the SPAC may engage in offerings known as private investments in public equity, or PIPEs, to raise additional cash prior to signing a definitive agreement with the seller. The PIPE transactions would close and fund immediately prior to the SPAC closing.

Typically, the SPAC will not pursue PIPE transactions until the definitive agreement with the seller has been fully negotiated, but not yet signed. If the PIPE transactions do not attract enough investment, the SPAC and the seller may need to renegotiate the transaction price. Essentially, like the SPAC stockholder redemptions, PIPE transactions act as a “market check” on the SPAC’s transaction price.

Although a reduced price is not desirable for the seller, the seller will have spent significant time negotiating the terms of the transaction with the SPAC and may feel compelled to continue with the SPAC rather than invest the time and money necessary to seek out an entirely different buyer. Even if the PIPE transactions attract enough investment, the seller is now exposed to third-party performance risk (i.e., the risk that the PIPE investors do not fund at closing).

Even if the SPAC has enough IPO proceeds held in trust and funds from PIPE investments, if applicable, to close the transaction with the seller on the terms originally negotiated, excessive redemptions can leave the post-closing business with less liquidity than anticipated, which, among other things, may adversely impact the SPAC’s stock performance following closing.

The Aftermath of a SPAC Transaction

Once a SPAC transaction closes, the seller will have investment risk if it received SPAC equity in the transaction. The SPAC equity that the seller receives in the transaction may be subject to a contractual lock-up, or the seller’s position may be too significant to liquidate quickly. This means the seller may have to bear the risk of its investment in the SPAC for an extended period.

Most SPAC transactions experience a year or more of high trading volatility and depressed stock prices following closing. In fact, more than 60% of the energy companies acquired by SPACs since 2016 are trading at prices below the SPAC’s stock price at the time the transaction closed. This suboptimal post-closing trading can be caused by a number of factors, including sell-offs by short-term institutional investors and the trading overhang created by “founder shares” and warrants.

In an environment where traditional capital markets are insufficient to provide liquidity events for private energy companies, SPACs serve an important function. Currently, around $2.6 billion in available capital resides in energy-focused SPAC trust accounts. However, the challenges described here and the historically weak trading price for energy-focused SPACs following closing should give any seller pause.

In addition to transaction price, sellers should consider how they can structure their transaction with a SPAC to address these challenges and insulate themselves, to the extent possible, from investment risk in the SPAC’s equity.

Troy Harder is a partner at Bracewell LLP and advises clients in corporate and securities law, with an emphasis on corporate finance transactions. Jason Jean is a partner and has experience in advising public and private businesses, including private-equity investors, in the financial service sector, upstream and midstream energy sector, and other sectors. Jared Berg is an associate and works with privately and publicly held companies, as well as their private-equity investors, in mergers, acquisitions and general corporate matters.

Recommended Reading

CERAWeek: Large Language Models Fuel Industry-wide Productivity

2024-03-21 - AI experts promote the generative advantage of using AI to handle busywork while people focus on innovations.

TGS, SLB to Conduct Engagement Phase 5 in GoM

2024-02-05 - TGS and SLB’s seventh program within the joint venture involves the acquisition of 157 Outer Continental Shelf blocks.

2023-2025 Subsea Tieback Round-Up

2024-02-06 - Here's a look at subsea tieback projects across the globe. The first in a two-part series, this report highlights some of the subsea tiebacks scheduled to be online by 2025.

StimStixx, Hunting Titan Partner on Well Perforation, Acidizing

2024-02-07 - The strategic partnership between StimStixx Technologies and Hunting Titan will increase well treatments and reduce costs, the companies said.

Tech Trends: QYSEA’s Artificially Intelligent Underwater Additions

2024-02-13 - Using their AI underwater image filtering algorithm, the QYSEA AI Diver Tracking allows the FIFISH ROV to identify a diver's movements and conducts real-time automatic analysis.