[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the September 2020 issue of Oil and Gas Investor magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

When Thunder Valley 2-1H was completed in Scurry County, Texas, on the Permian Basin’s Eastern Shelf in September of 2016, there were five rigs drilling in the county, according to Enverus data.

That was up from one just a few months earlier and down from 28 in the summer of 2014.

With an intriguing new conventional, horizontal play demonstrated by Thunder’s operator, Three Span Oil & Gas Inc., the count grew—totaling 10 this past winter. The count fell again to just one in July, but producers with leasehold for this hot spot of prolific Strawn section are planning to get back to work.

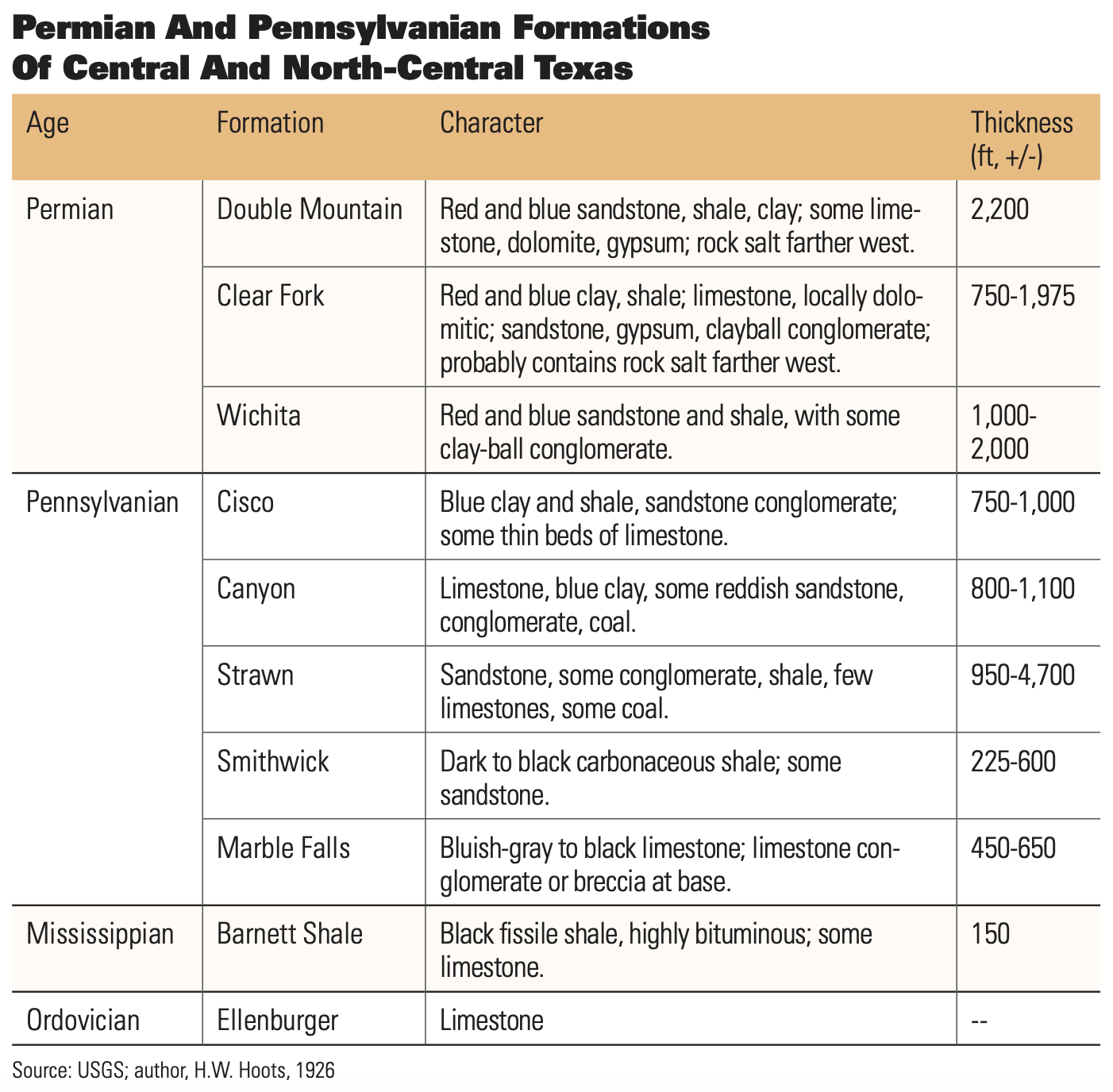

Conventional, vertical production in Scurry County began in the late 1930s from shallow wells, contributing 303,000 bbl of oil in 1944 to the war effort, according to the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA).

The deeper Canyon Reef, sitting on top of Strawn, was tapped in 1948, and county production grew to 94 MMbbl in 1974. By 1991, Scurry had made a cumulative 1.8 Bbbl of oil, according to the TSHA.

Recent E&P acquisitions on the Eastern Shelf indicate new interest in the area. Apache Corp. sold its Scurry and neighboring holding in the area earlier this year to a privately held firm. Additional details were not disclosed.

In early 2019, Mid-Con Energy Partners LP sold most of its Eastern Shelf property for $60 million to Scout Energy Group IV LP in counties north, east and south of Scurry.

There are about as many operators in Scurry today as the county’s population per square mile.

To the maps

Among them, Midland-based Moriah Energy Investments LLC is part of the family office of father and son wildcatters Dale and Cary Brown. The latter left Legacy Reserves Inc. in 2015, and the family office got back into oil and gas.

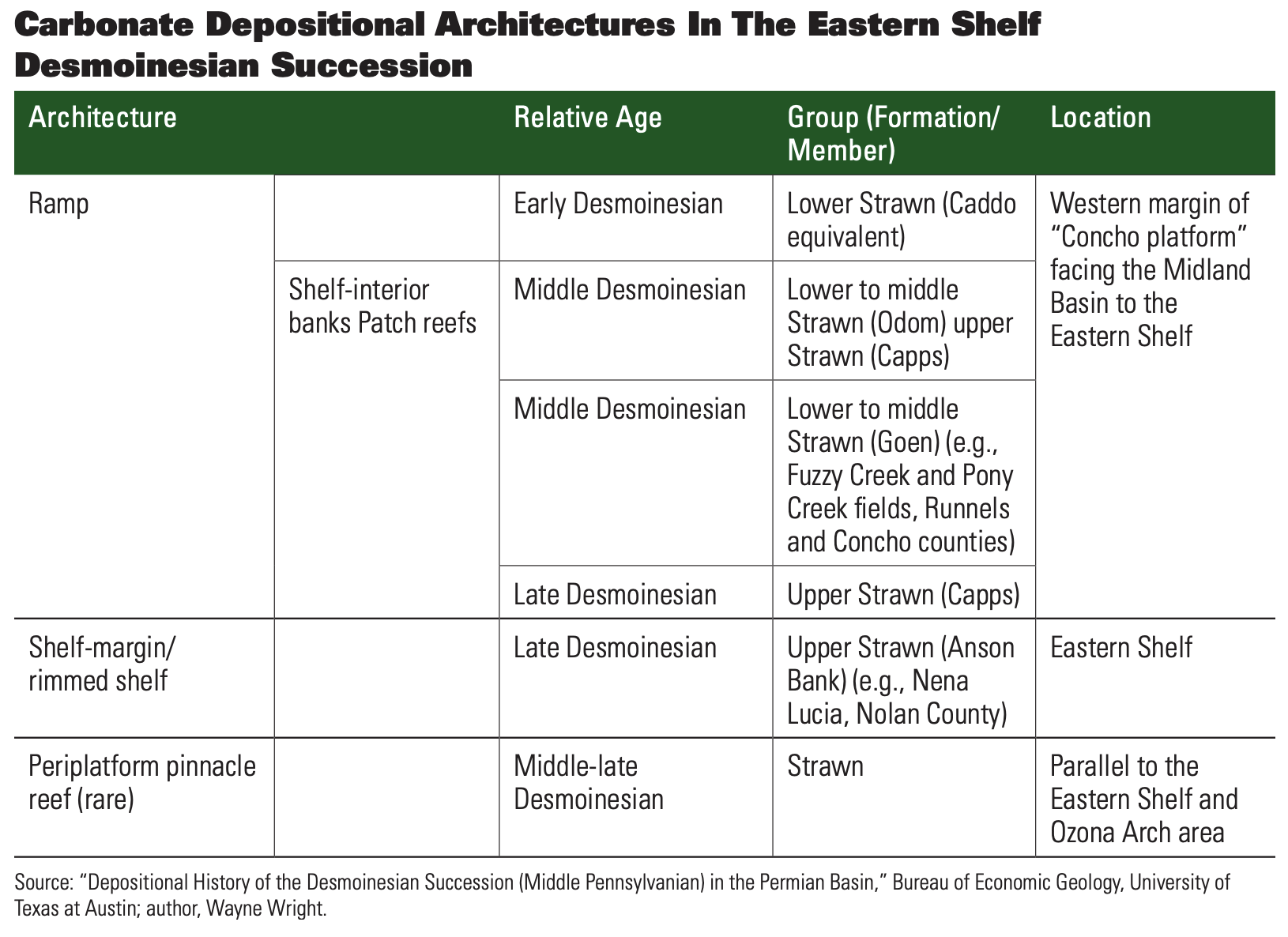

On the Eastern Shelf these days, Moriah is drilling a single bench, the Strawn, born in the Desmoinesian stage of the Pennsylvanian period and sitting at between 6,000 and 7,500 ft.

“Geologically, it gets a little bit more complicated than that, but it is Strawn-aged, more specifically [Middle Desmoinesian] Odom Sand,” said Tyler Harris, Moriah CFO.

“It’s a fairly small play that’s largely held by family offices. But it’s fairly well delineated at this point, so we’re now mostly focused on retaining leasehold and drilling it out.”

Vertical Strawn production elsewhere was from conventional-porosity, coarser-grain sands in the second half of the past century. In Moriah’s area, the sand is finer, thus the reservoir is tighter.

“People had tried to develop it conventionally, unsuccessfully,” Harris said. “But, with the advent of horizontal drilling and frac technology, we made those tighter parts of the reservoir accessible and economic.”

Moriah and other operators have landed 30 wells so far in the play; among them, Moriah has three, all of them 1-mile laterals. It had one DUC in mid-summer that it planned to complete this month.

“We haven’t gotten to the stage where we are in a continuous development program,” Harris said. The company is evaluating each well and learning more before it resumes drilling.

Moriah’s portfolio on the Shelf includes some legacy horizontals and verticals. But “We took brand new leases for much of this,” Harris said.

In 2015, another operator, privately held, Dallas-based King Operating Corp., tried horizontal technology in Strawn in a vertical well in Scurry County and found it to be prolific.

King followed that initial test with a second well. In 18 months, beginning in the summer of 2015, it closed three Scurry County Drilling Fund LPs, raising a total of $37 million to test Strawn as well as black Penn Shale.

“We leased what we thought was geologically similar to those [King] wells,” Harris said.

Moriah’s leasehold is 6,000 net acres with all but about 120 of them Moriah-operated, “and we’re still adding a little bit here and there,” Harris said, “increasing what’s within our existing blocks.

“This is a stratigraphic play instead of having a blanket of several 100,000 acres out there. Depending on who you talk to, there are 30,000 to 50,000 acres that are going to be prospective in this area.

“So nobody’s amassed a massive acreage block. That’s lent itself to the family offices that are the developers out here. Everyone’s kind of working from their own balance sheets as they’re drilling these wells.”

Moriah’s 6,000 net acres—in Scurry and Fisher counties—aren’t HBP yet except for the three wells it’s drilled and completed so far. Two of the horizontals were completed in what’s known as the Camp Springs Field with a $10 million loan last year from Production Lending LLC.

From well results Moriah has seen to date, “We think, on a one-mile lateral, you’re going to get somewhere between 400,000 and 500,000 bbl of oil,” Harris said.

Drilling and completion costs (D&C) were $5.5 million a well; Moriah estimates the cost today would be between $4.5 million and $5 million.

The first one, Tigger 1H, is public data now; its cumulative production is more than 150,000 bbl of oil.

“Your 24-hour max rate on these gets to be about 650 to 700 [bbl/d]. We’ve certainly seen rates north of that recently. But we think 650 to 700 is a somewhat predictable rate.”

The 30-day average is about 600 bbl/d on Moriah’s three wells to date.

From the results of the two play-opening wells by King, “We knew that there was something here that was going to work,” Harris said.

Otherwise, it seemed unlikely. “When we were looking at it over and over, our geologist just kept saying, ‘If you didn’t have those two wells’ results, I’d never drill this. There’s nothing about this on a log that looks to me like it ought to be productive.’”

Among reasons: “The water cut would be too high. The pressure doesn’t seem to be there.”

The reservoir is normally pressured, and the operators in the play report a water cut of a third to more than 80%.

There were many reasons one wouldn’t go after it, Harris said, “but here we are.”

Enter and watch

Moriah picked up its entry leasehold in 2017 and waited, watching others drill 15 wells and trucks hauling oil from tanks on a consistent basis, suggesting the volume as well as that the wells weren’t depleting.

“We sat on those acres for about as long as we thought we could,” Harris said.

Moriah picked up a rig in late 2018. “By the time we put the drillbit in the ground, we didn’t need to have a tremendous amount of faith that this was going to be productive.

“Maybe it wasn’t ‘proven,’ but it was certainly in that ‘probable’ range.”

Getting a frac spread and some other special services out to the Shelf had been challenging when the greatest demand for services was in the Delaware and Midland basins.

But getting a rig to the Shelf wasn’t too difficult, he said. “We’ve really always been able to find somebody wanting to do it,” Harris said.

This is due, in part, because the rig specs that are needed aren’t as demanding as those needed for multipad development.

“The rigs [we use] really weren’t designed to walk and be super-efficient in a way that a Pioneer [Natural Resources Co.] would need them to be,” Harris said. “We really were a home for some of the rigs that couldn’t compete for that work.”

Completions are no different than in the Delaware and Midland basins, though. So “You were trying to find somebody who is moving a completion crew from one job to the next and happened to have a 20-day window.”

With the Shelf play’s target being at a shallower depth, Moriah’s wells are economic at $40 oil with D&C at $4.5 million.

Adding oil

Also privately held, Verado Energy Inc. has been working on its horizontal program for the sandy Strawn beginning in 2015.

Allen, Texas-based Verado’s history dates to 1968 in East Texas, and it currently operates about 150 wells there in 15,000 net acres and has an interest as well in 500 nonoperated wells.

“We’ve gotten pretty good at identifying areas that have potential for increased production and improved performance through horizontal development,” said Christopher Graham, Verado president and CEO.

Graham joined the E&P in 2013, and it began looking to add property outside East Texas and at adding more oil to its 97%-natgas portfolio.

In Scurry County in the vertical Hermleigh East Field, it looked at logs on old wells. No horizontals had been drilled there yet.

“We thought the acreage had some promise for horizontals in the sandy, limey section of the Strawn,” Graham said.

Verado drilled its first well, Dessie 91-1H, in 2015 and with a half-length horizontal test. “It came out spectacular. So we started to feel really good about it.”

It landed two more wells—both of them full-mile laterals. “And they came in really great.”

So it added leasehold. It operates about 4,000 net acres, mostly HBP, on the Shelf now and has 12 horizontals in its bag. It’s looking at landing some laterals of more than a mile.

Water cut is about 70%. “Some people might say that’s a pretty high water cut. But it’s quite a bit of oil that we’re getting out of it—about 500 [barrels per day],” Graham said.

“So I don’t mind. I don’t mind it at all.” The 1-mile laterals, D&C’ed, cost about $4.5 million now. As Verado typically drills a few wells at a time, it’s been able to schedule back-to-back completions.

Except for one time when it had to wait, “We haven’t had too much trouble getting them out to work with us,” Graham said. It has no DUCs. In 2019, it had paused drilling while watching earlier well results just to see, long-term, how the production would hold up and compare it to different areas.

The pause was fortunate as it was getting pre-March 2020 prices for its production and not paying pre-March 2020 service prices. “When we were ready to pick it up again in late 2019 and early 2020, [oil] prices had started to come down.

“So we intentionally held off [further] at that point. We were fortunate enough to have our pause while prices were still relatively high and all of our wells completed and online.” It shut in production for about two months this spring and had the wells turned back on by June 1.

Fracture length

Because Verado is inducing fractures in a conventional reservoir, it’s especially mindful of well placement, as fracture lengths extend farther in less-tight rock than in tight rock.

“So how close do you want to space? I don’t think the jury is completely out on that yet,” Graham said.

“It takes some time to pull all the production together and see what the impact is on offset wells. But it’s one of the things we’re definitely studying.”

For one-section laterals, Verado’s proppant loading is about 1,200 lb/ft; pressure is with 30 bbl of water per foot.

“You don’t need to frac these like a shale,” Graham said. “The permeability is greater in the Strawn. It just doesn’t need as many pounds per foot to stimulate it and get the kind of rates you’d like to get.”

Remaining in debate, though, is whether to put a shale-size stimulation on one well and have the one well drain more area for less total D&C cost than that of multiple wells.

“Or do you put a relatively smaller frac on more wells in the field? It becomes a balance to try to optimize capital employed and what you think you’ll get back,” Graham said.

Overall, the horizontal Strawn has made a nice addition to the Verado portfolio. “We’re excited about the Shelf. The horizontal wells are not as expensive to drill or operate as in other areas.

“So we get good reserves and better all-in economics. It’s still economic—even at today’s commodity price—to go after it.”

In this downturn and as it has in-house capital access, Verado is looking at property to add to its inventory, Graham said, while, recently, “We may not have been as competitive, certainly not against the private-equity model.”

And it is looking to pick up partners that “share the same long-term mentality.” Among its past 125 drilled and operated wells—all but 12 of them in East Texas—only one was unable to reach TD. And only one was a dry hole, he said.

It’s looking there and in the Shelf for portfolio additions, as “Our preference is to start with what we’re the most familiar with.

“But we’re definitely open to opportunities outside of that.”

Word from Scurry

John Carr heard early on about a potential horizontal play in the Eastern Shelf. With an entry of 5,500 acres, its leasehold has grown to some 8,700 gross, 6,900 net, all in Scurry County, said Carr, president of Tyler, Texas-based Carr Resources Inc.

The company is targeting the Strawn A reef, but the sands in the Strawn B and C are also prospective, Carr said.

The overall reef play is up to 125 ft thick, about 10 miles north/south and about six miles wide. “It looks like a watermelon in shape. It’s just a big patch reef, but it covers 60 square miles.”

The targeted Strawn zones had oil shows when drilling through it with verticals in the past, he said, “but nobody ever completed in it. The first horizontal well that was [brought online] changed the game.”

Carr’s one well to date, the 7,000-foot-lateral Wolters 239-1H, was a 3,500-foot offset to Three Span’s Thunder Valley 240 1H.

Carr’s Wolters came in with 1,513 bbl/d in December and cumulative was more than 200,000 bbl, averaging 977 bbl/d, in roughly its first six months.

It plans to pick up a rig again this fall. D&C for a 1.5-mile lateral has declined from $5.8 million to about $4 million, he said. “So the economics are just about the same as they were last year [at a higher oil price] because of the fall in service prices.”

Carr Resources had a string of exploration successes in the past decade in East Texas in what became the Woodbine Sand horizontal play, the Lower Woodbine Shale play (aka Eagle Ford) and, most recently, the deep, horizontal Austin Chalk gas play.

Carr was looking more recently for overlooked tight oil in conventional rock that could be developed with laterals. “The Strawn A reef fit with our plans not only for the reservoir but the depth and excellent economics.”

It’s a Phylloidal reef. To describe it: “You think of a bowl full of cornflakes,” he said. “The reef has all these irregular plates with void spaces between them. But they have a lot of structural strength.

“So, when they were buried, they held up, and the voids are preserved as porosity.”

At 7,200 ft in depth and with a 7,500-ft lateral, well costs “are low for what will make in the range of 800,000 bbl of oil per well,” he said. “We like the area and are currently doing regional mapping for other bypassed pays in all three of the Strawn intervals.”

‘So I bought it’

Two landmen had leased around Three Span’s gusher “in kind of a horseshoe” shape. “I looked at the 5,500 acres they put together and said, ‘There’s nothing wrong with this.’ So I bought it from them,” Carr said.

Looking at old verticals that had been fracked in the Strawn, “They were little fracs and made 25 bbl/d.” Fracking that section over 7,000 ft of lateral, every 200 ft, would be hundreds of barrels a day.

“And that’s what we did. We’ve averaged almost 1,000 bbl/d since that well came on. It’s still flowing,” he said.

“That’s what we were looking for: conventional reservoirs that hadn’t been exploited because they were regarded as too tight, but could be completed with moderate-length laterals and multiple fracs.”

Water cut is about a third—about 500 bbl/d with 1,000 bbl/d of oil. For now, Carr is sending it to a disposal well.

In its one well, the company used 8.5 million lb of sand and 188,000 bbl of water over the 7,065 ft of completion interval. “It’s a lot like a shale frac,” he said.

He’s continuing to add to leasehold.

Recommended Reading

EIA: Permian, Bakken Associated Gas Growth Pressures NatGas Producers

2024-04-18 - Near-record associated gas volumes from U.S. oil basins continue to put pressure on dry gas producers, which are curtailing output and cutting rigs.

Exclusive: Mitsubishi Power Plans Hydrogen for the Long Haul

2024-04-17 - Mitsubishi Power is looking at a "realistic timeline" as the company scales projects centered around the "versatile molecule," Kai Guo, the vice president of hydrogen infrastructure development for Mitsubishi Power, told Hart Energy's Jordan Blum at CERAWeek by S&P Global.

Benchmark Closes Anadarko Deal, Hunts for More M&A

2024-04-17 - Benchmark Energy II closed a $145 million acquisition of western Anadarko Basin assets—and the company is hunting for more low-decline, mature assets to acquire.

US Orders Most Companies to Wind Down Operations in Venezuela by May

2024-04-17 - The U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control issued a new license related to Venezuela that gives companies until the end of May to wind down operations following a lack of progress on national elections.

Google Exec: More Collaboration Needed for Clean Power

2024-04-17 - Tech giant Google has partnered with its peers and several renewable energy companies, including startups, to ramp up the presence of renewables on the grid.