Presented by:

More than seven years after the issue of frac-driven interactions (FDI) were first identified, operators are still trying to determine which well spacing patterns can both optimize production while also mitigating risk factors. Completion designs, well economics and the age of a play are also factors producers are considering when trying to better understand FDIs.

“If there is a risk of interference in the oil production, if you space the wells too tightly, that doesn’t necessarily mean that upspacing is always going to lead to better productivity because it really also depends on the rock and on the completion and on a whole lot of different factors,” said Amanda Richardson, senior research analyst with Wood Mackenzie. “So it’s not as clear cut of a trend as you might expect between productivity and spacing. It’s just a risk that needs to be mitigated basically.”

Wood Mackenzie recently compiled a report studying well spacing and productivity in the Permian and Eagle Ford basins. The study looked at well densities in both plays compared to basin maturity, the effect of co-completions on wells and single-well economics versus full section development economics.

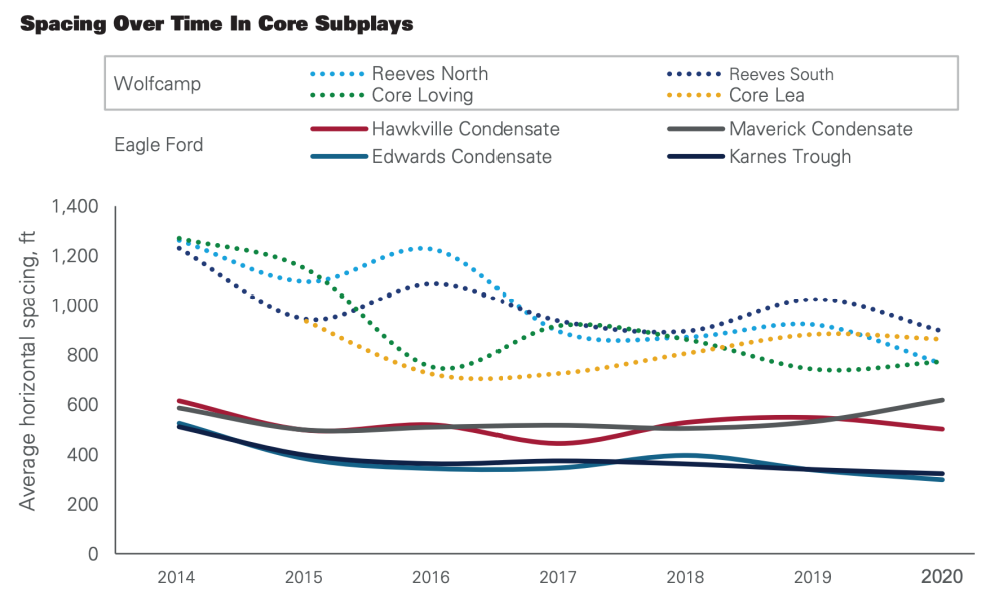

Wood Mackenzie found that multibench developments are more common in the Permian Basin’s Wolfcamp development, which likely contributes to wider spacing on average than in the Eagle Ford.

“In the Eagle Ford, they are using much tighter well spacing, around 330 ft on average versus in the Wolfcamp, it’s 600 ft to 800 ft,” Richardson said. “In the Wolfcamp, you see multibench developments a lot more often. Those are staggered between the two benches, where as in the Eagle Ford you see more of that but also it’s just much more drilled out and there’s not as much room. So operators are getting the most value out of the acreages they have by fitting those wells in.”

According to Wood Mackenzie, the average horizontal spacing in the Wolfcamp in Reeves, Loving and Lea counties was about 1,300 ft in 2014. Since then, that spacing distance has declined to between 800 ft and 1,000 ft. In the Eagle Ford, well spacing distances have only varied slightly, particularly in the Hawkville and Maverick condensate plays where wells have typically been spaced about 600 ft apart. In the Edwards Condensate and Karnes Trough, the two most productive Eagle Ford subplays, average horizontal spacings have declined slightly from about 500 ft in 2014 to about 300 ft in 2020.

“[Well spacing in the Eagle Ford] really hasn’t changed a lot in the past three years,” Richardson said. “Prior to that there was more downspacing, but in recent years when you look at it on an average level at the subplays, it’s been fairly consistent.”

“I think the key question that is asked as operators theoretically continue to upspace [is] do you see performance follow or is it one where they just mitigated some of that risk of performance rolling over like we’ve seen in the Eagle Ford and portions of the Delaware Basin?” —Ryan Duman, Wood Mackenzie

Production increases?

Despite the plateauing of well spacing, particularly in the Eagle Ford, Wood Mackenzie found those efforts haven’t necessarily led to production increases.

“The performance hasn’t shown a corresponding uptick though, and that’s where it’s hard to parse out the multivariate aspect of all of this and how impact spacing alone has,” said Ryan Duman, principal analyst, Lower 48 upstream with Wood Mackenzie.

He provided an example of the Midland Wolfcamp, where production related to well spacing has remained “about flat.”

Duman added, “I think the key question that is asked as operators theoretically continue to upspace [is] do you see performance follow or is it one where they just mitigated some of that risk of performance rolling over like we’ve seen in the Eagle Ford and portions of the Delaware Basin?”

Wood Mackenzie analyzed the impact co-completions along with upspacing might have on well performance and determined that while tightly spaced wells performed better if they were co-completed, they still underperformed more widely spaced wells on average. According to Wood Mackenzie, co-completed wells in the Midland Wolfcamp with wide spacing (defined as 660 ft or more) produced about 35 boe/ft after 36 months on production, similar to wide-spaced wells that were not co-completed. However, tightly spaced wells that were not co-completed saw production fall to less than 30 boe/ft. Co-completed tightly spaced wells performed only slightly better, just over 30 boe/ft.

Over the years, there have been a variety of efforts and technologies emerge to help alleviate FDIs, some with more success than others. Proppant tracing and real-time pressure monitoring have each proven beneficial to varying degrees, but well spacing remains an inexact science.

“We’re years down the line, and there’s no simple solution or agreed upon solution that folks can employ,” Duman said. “Generally, spacing is going to mitigate that risk or tailor completion design or other things to impact performance. It’s dependent on individual operators and what rock they’re actually trying to exploit, which can make it challenging to try and do more of the basin-wide or very wide macro analysis.

In an analysis of Karnes Trough P50 type curves, Wood Mackenzie found that wells spaced 330 ft to 660 ft apart would be expected to recover about 10% more barrels per foot than wells spaced less than 165 ft apart. Widely spaced wells recovered about 44 boe/ft in the Karnes Trough, while tightly spaced wells recovered about 39 boe/ft.

“If you look at sections, levels, NPV [net present value], payback or whatever metric of choice as you start to move wider, say six wells per section, you start sacrificing the amount of resource you’re going to develop and the overall value starts to decline again,” Duman said. “So it’s trying to balance that sweet spot of how much resource overall you can develop while accepting that individual well performance isn’t necessarily going to be the best that it possibly can be.”

Recommended Reading

BP Restructures, Reduces Executive Team to 10

2024-04-18 - BP said the organizational changes will reduce duplication and reporting line complexity.

Matador Resources Announces Quarterly Cash Dividend

2024-04-18 - Matador Resources’ dividend is payable on June 7 to shareholders of record by May 17.

EQT Declares Quarterly Dividend

2024-04-18 - EQT Corp.’s dividend is payable June 1 to shareholders of record by May 8.

Daniel Berenbaum Joins Bloom Energy as CFO

2024-04-17 - Berenbaum succeeds CFO Greg Cameron, who is staying with Bloom until mid-May to facilitate the transition.

Equinor Releases Overview of Share Buyback Program

2024-04-17 - Equinor said the maximum shares to be repurchased is 16.8 million, of which up to 7.4 million shares can be acquired until May 15 and up to 9.4 million shares until Jan. 15, 2025 — the program’s end date.