A Marcellus shale drilling site in northern Pennsylvania, pipeline construction and an LNG tanker are shown. (Source: George Sheldon/Reinhard Tiburzy/Wojciech Wrzesien/Shutterstock.com)

North America’s prolific natural gas fields likely won’t have difficulty producing enough gas to meet domestic demand and the world’s burgeoning LNG needs, according to analysts, but uncertainties—including those surrounding infrastructure—still exist.

“If it were a country on its own, it would actually be the world’s third-largest gas producer,” Alastair Nojek, analyst for McKinsey & Co., said of the Appalachia Basin during a recent North American gas perspectives webinar. “However, new pipelines will be needed in the long term or production will again become constrained.

“Given the difficulty seen during the last wave of pipeline buildout, Appalachia infrastructure remains a key uncertainty for the North American gas market,” he added.

Gas production in Appalachia, home of the Marcellus and Utica shale formations, is projected to hit 32.6 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d) in September, up 367 million cubic feet per day (MMcf/d) in August, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s latest Drilling Productivity Report. The top-producing U.S. gas basin is followed by the top oil-producing one, Permian Basin, where gas production could near 14.9 Bcf/d next month.

Increased LNG flows from the U.S. are expected to come as global demand grows in other parts of the world, particularly Asia and Europe, and the world turns toward cleaner sources of fuel such as natural gas.

Together, Appalachia and Permian are expected to supply about 53% of the North American gas market by 2030 and represent about 83% of the growth, according to McKinsey.

Associated gas from the Permian Basin, which has also faced infrastructure challenges, could see its production grow by about 7.2 Bcf/d to 2030.

RELATED: Report: Permian Basin Still Needs Additional Pipeline Investment

While Appalachia and Permian are seen as the drivers of North America gas growth, others are also expected to play notable roles. These include Oklahoma’s Scoop/Stack and the Haynesville, given their proximity to Gulf Coast export facilities.

But don’t count out the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin (WCSB), where the firm said Montney gas production is growing with Western Canadian LNG providing possible upside.

Changing Flows

However, as Appalachia has debottlenecked, gas flows have changed across North America, McKinsey & Co.’s Jamie Brick pointed out. He explained how Midwest-destined volumes from Appalachia have displaced some supply from WCSB and the Rockies, “which must now compete for a shrinking market along the West Coast and have resulted in lower gas prices.”

Appalachian gas is also flowing to the Gulf Coast, as LNG exports drive demand for associated gas. But its flow to the south has also been limited primarily due to the better-positioned Permian and Scoop/Stack, which happens to also be ceding some of its traditional upper Midwest market to Appalachia, Brick said.

“In short, Appalachia will supply an increasingly large part of the continent, limiting the WCSB and Rockies, while associated gas from the Permian and Scoop/Stack are supplying nearby growing demand in the Gulf Coast,” he said.

McKinsey & Co. forecast gas demand in the U.S. Gulf Coast will grow by about 17 Bcf/d by 2030 on global LNG exports, including to Mexico. The growth means new pipelines to the coast will be needed not only in Appalachia but also in West Texas.

If that doesn’t happen, WCSB would be the “primary beneficiary,” given its plentiful resources and existing pipeline capacity, Brick said, adding “WCSB could increase production by over 6 Bcf/d and conserve its traditional markets in the upper Midwest.”

Plus, higher production could also be in store if LNG Canada decides to expand trains 3 and 4, he added later. LNG Canada joint venture partners Royal Dutch Shell Plc, Petronas Gas Bhd, Mitsubishi Corp. and Korea Gas Corp. took a final investment decision in 2018 to build the export facility in Kitimat, British Columbia.

The Rockies, which could see its production grow by 1.6 Bcf/d, would also benefit, Brick said, noting a “modest resurgence” of the Fayetteville as well.

Gulf Coast, Beyond

Though increasing demand is seen coming from Mexico and the power and industrial sectors, LNG leads the anticipated percentage of overall growth demand through 2030 at 58%, according to Dumitru Dediu, the McKinsey partner who leads the global gas and LNG team.

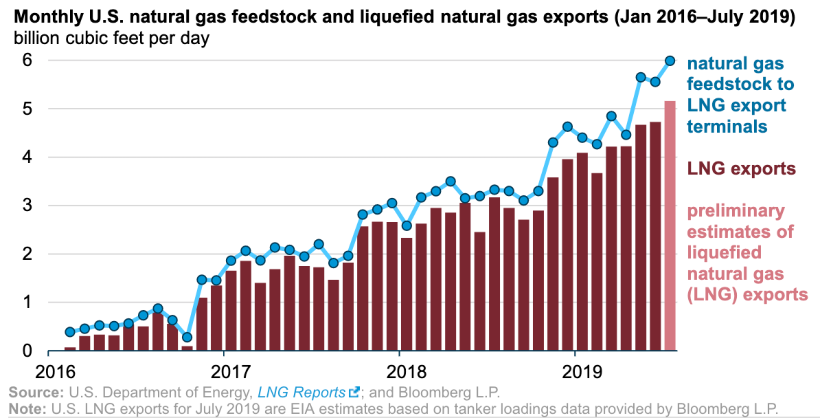

Citing data from OPIS PointLogic Energy, the EIA on Aug. 19 said natural gas deliveries to U.S. facilities producing LNG for export reached an average 6 Bcf/d, a monthly record, in July. The amount equated to 7% of the total U.S. dry natural gas production.

“We expect demand in North America to increase by roughly 30 Bcf/d from 95 Bcf/d today to 125 by 2030,” said Dediu. “Of that, roughly two-thirds will be driven by gas exports, especially LNG.”

LNG export capacity could surpass 10 Bcf/d by 2020-2021 and reach more than 20 Bcf/d by 2026-2027, he said, adding most the additional capacity required is already under construction.

But the U.S. is still considered a high-cost supplier of LNG, despite its ample resources with gas below $3. Dediu explained that unlike conventional integrated LNG projects, U.S. LNG projects have a high cash cost for feed gas and liquefaction charge. In addition, shipping costs due to its distant proximity to destination markets such as Asia is a contributor.

“With North America becoming one of the largest LNG exporters in the next five years, Henry Hub will become an important price marker for marginal LNG supply,” according to Dediu’s presentation.

In July, the International Energy Agency’s senior gas analyst said the U.S. would pass Australia and Qatar to become the world’s biggest LNG exporter with exports of more than 100 billion cubic meters in 2024, Reuters reported. The biggest importer is expected to be China.

Recommended Reading

Benchmark Closes Anadarko Deal, Hunts for More M&A

2024-04-17 - Benchmark Energy II closed a $145 million acquisition of western Anadarko Basin assets—and the company is hunting for more low-decline, mature assets to acquire.

‘Monster’ Gas: Aethon’s 16,000-foot Dive in Haynesville West

2024-04-09 - Aethon Energy’s COO described challenges in the far western Haynesville stepout, while other operators opened their books on the latest in the legacy Haynesville at Hart Energy’s DUG GAS+ Conference and Expo in Shreveport, Louisiana.

Mighty Midland Still Beckons Dealmakers

2024-04-05 - The Midland Basin is the center of U.S. oil drilling activity. But only those with the biggest balance sheets can afford to buy in the basin's core, following a historic consolidation trend.

Mesa III Reloads in Haynesville with Mineral, Royalty Acquisition

2024-04-03 - After Mesa II sold its Haynesville Shale portfolio to Franco-Nevada for $125 million late last year, Mesa Royalties III is jumping back into Louisiana and East Texas, as well as the Permian Basin.