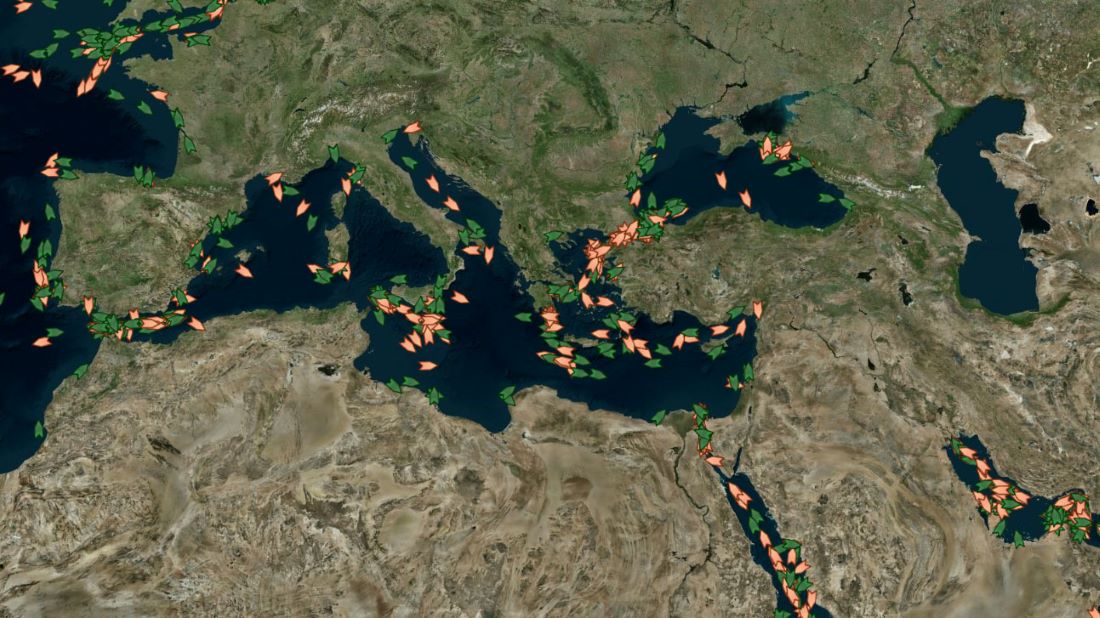

As many as 600 ghost tankers ferry Russian crude oil and oil products to markets at high risk and reduced prices. (Source: Shutterstock.com)

Russia’s huge fleet of “ghost crude tankers” succeeds in generating revenue and evading western sanctions, but at great cost and considerable risk, a global energy expert told Hart Energy.

“They’re adding friction, they’re adding cost to the system, some of which is being born by Russia in the form of discounting crude oil to find new homes for it,” said Mark Finley, fellow in energy and global oil at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. “There are real costs in the system, for sure. We’ll have to see what it means for refined products because those are different tankers, they tend to be smaller.”

Ghost tankers are vessels that disguise their ownership and movements to move cargoes under sanction. They have been used to transport Venezuelan and Iranian crude for years.

“The oil market’s a big place with a lot of dark corners,” Finley said. “That’s not new. What’s new is the scale of what’s happening.”

Russia’s ghost fleet has expanded to about 400 crude carriers and about 200 oil product carriers, a Trafigura executive told Bloomberg Television. That constitutes about 20% of the world’s crude vessel fleet and about 7% of all oil product tankers.

Dodging sanctions

The higher cost of shipping Russian crude stems from several factors. Most crude oil in the world is transported on Very Large Crude Carriers with capacities of up to 320,000 dead weight tons (DWT), or 2.2 MMbbl. Aframax-class tankers, one of the types employed in the ghost fleet, are only able to haul about 160,000 DWT.

Reuters reported that a recent invoice showed the shipment of 700,000 bbl of Russian crude on an Aframax tanker from a Baltic port to an Indian refinery. The charge was about $10.5 million, compared to a cost in the range of $500,000-$1 million a year ago.

One trader in Russian crude told Reuters the business was “crazy good.”

But the older, smaller tankers pressed into service were likely on the verge of being scrapped, Finley said. They are more at risk for mechanical breakdowns, accidents or spills. The vessels may well be self-insured because sanctions have prevented western insurance companies from doing business involving Russian seaborne crude.

“The market’s full of characters who are happy to find creative ways of doing business, shall we say, if there’s money to be made,” Finley said. “In that sense, it’s not surprising to me that these embargoes have come into place without major disruptions to the marketplace.”

And it can be argued, he said, that new centers for shipping and insurance, and transactions that don’t use U.S. dollars, can develop in the global marketplace.

“The risk is that people find workarounds that, in the future, could undercut the leverage the U.S. and its allies have over our adversaries because we’ve hastened the development of these alternative systems,” Finley said.

He noted that Iranian entities have tutored their Russian counterparts on how to evade sanctions since the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. That doesn’t mean the world of international trade has gone over to the dark side. Not yet.

“The reason why the successful exchanges are in the west, and the successful insurance entities are in the west, and why the successful shipping companies are in the west, is because these are the places with competitive advantages in terms of rule of law and transparency,” he said. “While there is potential for these alternative channels to develop, they are likely to be more expensive, and therefore be a durable source of competitive disadvantage.”

Budget troubles

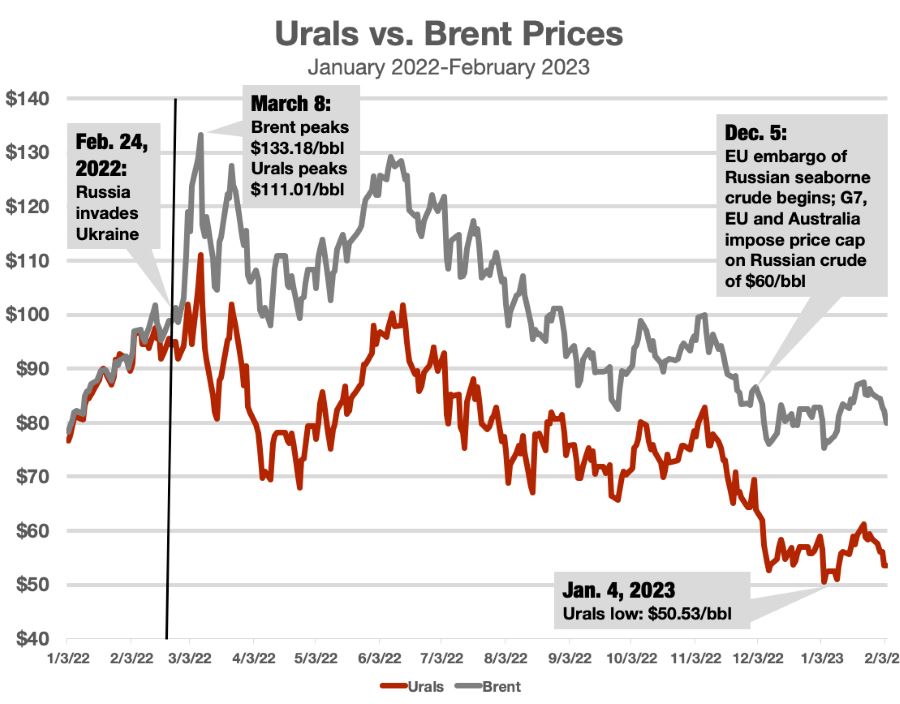

The EU’s ban on seaborne imports of Russian crude oil took effect on Dec. 5. A similar ban is now in place for diesel and other fuels. The group of leading industrial nations known as G7 imposed a price cap of $60/bbl on seaborne Russian crude in December.

Prior to the invasion, Russia’s Urals blend tracked Brent fairly closely. Since then, the spread has widened significantly. Urals closed at $55.12/bbl on the spot market on Feb. 7, well below international benchmark Brent’s mid-$80s.

Urals is a medium sour crude with sulfur content of 1.7% and API gravity of 31.7, which is broadly equivalent to Arab Light produced in Saudi Arabia. By comparison, WTI Midland, a light sweet crude, has a sulfur content of 0.2% and API gravity of 42.

Russia’s budget is based on a Urals price of $70.10/bbl. With Urals sold at a significant discount to just a few countries—India, Turkey and China, among them—the Russian federal budget registered a deficit of $25 billion in January. The month’s oil and gas revenues were down 46.4% compared to January 2022.

Urals is a sanctioned seaborne crude. However, Russian crude that travels east on the 2,600-mile Eastern Siberia Pacific Ocean oil pipeline traded closer to market price at $68.56/bbl on Feb. 8. That oil is shipped to Japan, China and South Korea.

The intent of the sanctions, Finley emphasized, was not to disrupt exports of Russian oil, but to reduce revenues and thereby hinder its war effort in Ukraine.

By contrast, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) sanctions against Iran were designed to stop Iranian oil from flowing altogether. The sanctions prevented transactions involving Iranian oil from moving through the western financial system and worked, in large part, because U.S. shale production was ramping up dramatically at the time.

Russia was the world’s second-largest exporter of both crude oil and oil products before the Ukraine war, putting the U.S. and allies in a tight spot. Allowing Russian oil to flow helps to keep prices low for U.S. consumers at the pump.

“This is a completely different approach than was used against Iran during the JCPOA,” Finley said, “and harder to make it stick because of that.”

Recommended Reading

US Drillers Cut Oil, Gas Rigs for Fourth Week in a Row-Baker Hughes

2024-04-12 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, fell by three to 617 in the week to April 12, the lowest since November.

US Drillers Cut Oil, Gas Rigs for Third Week in a Row

2024-04-05 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, fell by one to 620 in the week to April 5, the lowest since early February.

US Gas Rig Count Falls to Lowest Since January 2022

2024-03-22 - The combined oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, fell by five to 624 in the week to March 22.

US Oil, Gas Rig Count Rises to Highest Since September: Baker Hughes

2024-03-01 - The U.S. oil and natural gas rig count is at its highest since September 2023.

US Drillers Add Oil, Gas Rigs for Second Week in a Row

2024-01-26 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, rose by one to 621 in the week to Jan. 26.