[Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the March 2020 edition of E&P. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

When you think of the Shale Gale, you generally think of the tremendous economic advantages created by the astronomical production figures created by unconventional drilling. The most important part of unconventional production is, of course, hydraulic fracturing. However, while most people realize how important water is to this technique, they may not realize the staggering amount of water being produced and the tremendous need for water infrastructure in shale plays.

While oil, gas and liquids pipeline capacity is catching up to production, there is a huge demand for another set of pipelines related to the E&P sector—water pipelines. This need wasn’t even fully realized by midstream operators initially. Darrell Bull, chief commercial officer at H2O Midstream, told E&P that it was not until he heard the forecast from a large E&P company in the Permian Basin that he fully grasped how much water was being generated.

“This forecast was for about 200 million cubic feet of dry gas, which I thought was great because it was enough to fill a nice-sized gas plant. Then they said they’d be producing about 100,000 barrels per day of crude oil at their peak. I figured that would justify a 50-mile pipeline to a market hub. Then they added they’d peak at about 600,000 barrels per day of water. It took me about five seconds to decide that I needed to be in the water business because there was no one serving this segment at that scale,” Bull said.

Welcome to the evolution

Indeed, much of the history of the midstream industry saw one company handle oil, gas and water pipelines, aka “the three pipes in a ditch” method. But when you’re talking about volumes that high with a liquid that’s different than hydrocarbons, it has become more obvious that water specialists are needed in the space.

“The water industry has evolved from what used to be a downstream truck service to full midstream gathering and processing business,” Chris Cooper, CEO of Oilfield Water Logistics (OWL), told E&P.

He noted that while OWL has been operating in the water midstream space for more than a decade, the changes in the sector over the last five years have been significant, including moves to longer-term contracts and permanent water infrastructure.

“Six years ago, there weren’t really any long-term water contracts in the Permian. We established some of the first contracts in the space during the downturn in 2016, reflecting our commitment to build out reliable water infrastructure to support our customers’ operations. We focus on building and managing water infrastructure; they focus on oil and gas drilling. It’s a strong value proposition that solves a growing challenge in the sector,” Cooper said.

Nonconsumable product

The changes in the water midstream space may sound very familiar to those in the hydrocarbon midstream, but there are key differences between water and oil and gas. Unlike hydrocarbons, water isn’t consumed—it’s used and reused. That reality requires infrastructure designed to resupply facilities with these volumes again and again.

While unique to most products moved along a pipeline, it is not unusual for water as a whole. Dan Lippe, principal at Petral Consulting Co., noted that only 3% of all water on Earth is freshwater, and most of this is tied up in glaciers and polar ice caps, which require the consistent reuse of water.

“If freshwater on our planet was not recycled and reclaimed, Earth would have become a barren wasteland long ago. My primary point is this: We do not consume water. We just move it from one place to another,” Lippe told E&P.

This movement obviously requires pipelines, and this need is very similar to where midstream was about a decade ago. However, the water sector for oil and gas production shares more similarities with the midstream sector of the ’80s and ’90s.

“We’re still early innings for water pipelines, especially in the Permian,” Bull said. “I remember my days back in the ’90s seeing gas pipeline maps, and we would joke that Louisiana would fall off into the Gulf if it weren’t for all the pipelines holding it on. We’re starting to see the same thing now in West Texas with water pipelines. It’s estimated that $100 billion of water infrastructure will be needed over the next decade.”

Back then in the ’80s and ’90s, E&P companies were divesting their pipeline and processing assets to third-party companies that created the modern midstream industry. Bull, along with several other members of the H2O Midstream management team, was part of this changeover at both super majors and midstream companies.

“We see the same thing happening now with water. This is a pretty skinny business for a major E&P to participate in,” Bull said. “We monitor costs and work to give producers the cheapest destination all the time. We tease our E&P customers that they’re chasing the dollars per barrel while we’re chasing the pennies per barrel. We have to; their commodities are worth $60 per barrel. Ours, we might be getting 50 cents to less than a dollar per barrel. It’s the classic midstream outlook where you look at everything through a magnifying glass because of the smaller margin opportunity.”

A well-worn template

Monetizing these assets allows producers to get returns on underutilized assets while these midstream water companies are tying in these pipelines with other systems to ensure maximum reliability for the producer. In return, these operators are earning fees for transporting these volumes while still working closely with producers to make sure their needs are being met. It’s an easy win-win for all involved.

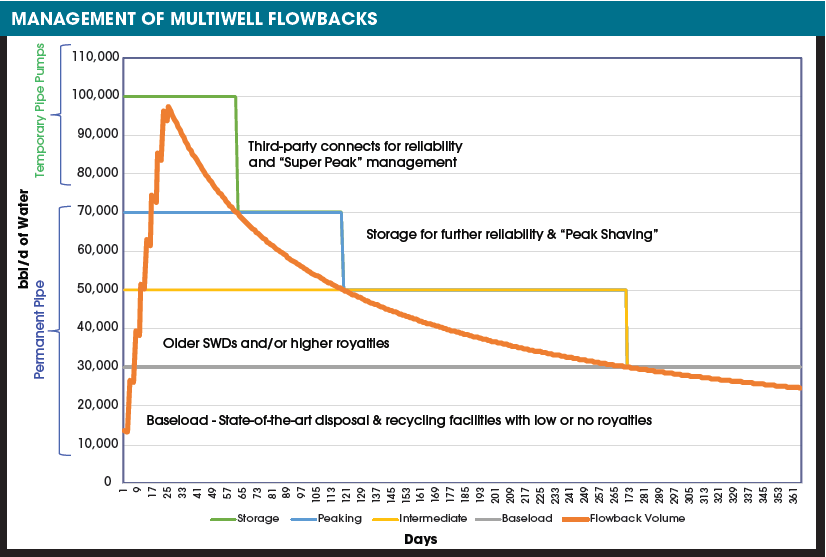

“Most of these systems were built for peak volumes originally and they were being underutilized based on the decline curve,” Cooper said. “It’s another reason I believe the E&P companies see these as great assets to move to a third party so they can be used more efficiently.”

This monetization of water assets is also helping make water services more reliable and flexible, according to both Cooper and Bull.

“Producers need operators that will ensure a reliable and sustainable option for their water,” Cooper said. “Our customers have a 20- to 30-year outlook and want permanent water infrastructure because the volumes are pretty staggering if you look at projected production. We’re seeing at least four barrels of water for every barrel of oil in the Permian Basin, if not more. If production is projected to double over the next five years, that’s eight times the amount of water.”

There are two destinations for fracked and produced water: disposal or recycling facilities. No matter how or where the water is being sent, it requires a large pipeline network to get there. According to Bull, producers need to be tied to a system that is doing at least 80,000 bbl/d, and more realistically about 120,000 to 200,000 bbl/d to meet their fracking demands.

“Being able to tie into a large, fully integrated pipeline system is a big selling point for producers, he said. “They know that if they sell to us and tie into our system, they will have the reliability of our assets, including 18 saltwater disposal (SWD) wells and our million-barrel pond.”

Shared access

Like oil and gas pipeline operators, water pipeline companies also seek to provide their customers with high levels of flexibility and reliability. This can be in the form of tying their systems into systems owned by other companies.

Bull said some other water pipeline operators questioned why they would want H2O Midstream to tie into their system, but they used the old midstream format to convince them it was a sound business practice.

“We said this is what we did in natural gas to improve optionality and flexibility. We asked for a small discount on using their lines in exchange for guaranteeing them business. We have a few contracts where the more we send to a third party we get discounts. The whole midstream philosophy of connecting to your peers is taking hold in this space,” Bull said.

Flexibility is also important in terms of various services being offered. Cooper said that OWL not only gathers water but has multiple reuse and disposal options along the way.

“If we have one customer disposing of produced water and another one needing it for a reuse project or a fracking project, we can take it in at one part of the system and then let the water out at another part and help them both out given our recently expanded 500-mile gathering system,” he said.

There are other similarities between water and hydrocarbon pipelines, such as similar contracts. Bull noted that producers typically prefer long-term acreage dedications when working with both gas gathering and water pipeline operators. One added benefit for producers with water is that midstream operators have the capital obligation to lay pipes to the well pad.

Another difference is that sometimes producers pay operators a disposal/recycle fee. On the operator side, pipeline maintenance is a bit less expensive for water pipes since there aren’t corrosion issues associated with carbon steel.

Hub strategy

Similar to midstream operators, water operators have related nonpipeline assets. In the case of H2O Midstream, this includes aboveground storage via several ponds with total capacity of 1 MMbbl.

These ponds were the first in Texas not required to post a bond by the Railroad Commission. “A high bond is typical for these assets because if the owner were to go out of business, the Commission will have to pay to have that water hauled out decades later. However, since our ponds are connected to different customers and saltwater disposal wells via pipeline, the costs and operation are significantly lower,” Bull said.

H2O Midstream calls this “the Newton Hub,” and while it’s not there yet, company officials dream of it one day becoming the Henry Hub of water in the Midland Basin.

“Every producer has acreage surrounding our footprint,” he said. “We have conversations with producers that are committed to running their own water pipelines and ask them to put a meter on their system to our system. These interruptible, or overflow, agreements are good for that one month a year that they overflow; they can just send those volumes to us. A few of these arrangements have led to producers moving all of their water to us after they see our high reliability.”

Cooper said that OWL has facilities spread across the region that will store water, including tank batteries, frac ponds and surge ponds. It will then recycle or reuse water out of these facilities.

Challenges and opportunities

While recycling is improving, it still has several challenges to overcome. “The biggest hurdle for recycling water is actually the logistics of getting the water from where it’s being produced to where it’s needed in sufficient quantities at the right time. That’s the only problem. It’s not treating. Roughly 10% of the water produced today finds its way to being used in a subsequent frac, but where you have good infrastructure, it could go beyond 50%,” Bull said.

The issue of how water is used in producing oil and gas is one of the general public’s biggest misconceptions. Cooper noted that though the volumes used in hydraulic fracturing are large, they are nowhere near the volumes used in the agricultural industry.

“There’s also a tremendous amount of reuse in the market, and most of our customers are highly concerned about the environment. They’re concerned about water resources, water scarcity and there’s certainly a conscious effort to be responsible and have a sustainable approach to managing water,” Cooper said.

When OWL first entered the Permian, producers only used freshwater in fracturing. This has changed dramatically, with some producers now only fracking with produced water. As reusing water has become more widespread, the cost to treat it has decreased significantly.

It is important to note that not every shale play requires extensive water pipelines. As plays develop, the need for water pipelines increases. Some plays in their early days, such as the Powder River Basin, remain largely dependent on trucks to transport water.

“The Powder River is a great basin, but still a little young, so this pipeline infrastructure will come over the next few years. It’s where the Delaware was three to five years ago,” Cooper said.

Since the Permian Basin is the focal point of the oil and gas industry, not surprisingly, it is also the focal point for water pipeline operators. Cooper noted that water activity in the northern Delaware Basin is growing rapidly with lots of gathering infrastructure, disposal and reuse assets.

OWL recently announced a major acquisition in the New Mexico part of the Permian that doubled the company’s infrastructure footprint in the northern Delaware Basin and enabled the company to extend a long-term contract with one of its customers. As an added benefit, OWL can make the system available for its other customers and new customers in the area.

“The biggest challenge is that volumes are more than the current infrastructure can handle. The amount of water that is produced with an oil well in the Greater Delaware is exponential. As you make oil and gas projections, you have to take at least a four factor, if not a seven, to come up with your projected water volumes. This sector requires billions of dollars in investment over the next five years. It’s definitely a capital-intensive business,” Cooper said.

While midstream water companies have been doing much of the acquiring of assets from producers, the field is becoming so attractive that major water companies are subjects of acquisitions to bring in more capital for expansion.

In October 2019, InstarAGF Assessment Management acquired OWL from NGP Energy Capital Management and NGP Energy Technology Partners for an undisclosed sum. Sarah Borg-Olivier, senior vice president at InstarAGF, told E&P that the company identified this sector as an attractive space that was emerging as an infrastructure-like asset.

“When the opportunity became available, we saw it as a great entry point into a market where we believe there is a lot of growth potential. We are proud to partner with a proven team and first mover in the space that is helping the E&P sector to solve water challenges in a way that is more environmentally

sustainable,” she said.

Read E&P magazine's March 2020 "Water Management Techbook" articles:

OVERVIEW:

Bringing Balance to Water Demands

KEY PLAYERS:

Meeting Water Management Demands

TECHNOLOGY:

Innovations in Water Management Technology

MIDSTREAM:

The Rise of Water in the Midstream (story above)

Recommended Reading

US Threatens to Not Renew Venezuelan Energy Sector License

2024-01-31 - The U.S. Department of State alerted Venezuela that it could decide not to renew General License No. 44 amid what Washington has labeled “anti-democratic actions.”

US Decision on Venezuelan License to Dictate Production Flow

2024-04-05 - The outlook for Venezuela’s oil industry appears uncertain, Rystad Energy said April 4 in a research report, as a license issued by the U.S. Office of Assets Control (OFAC) is set to expire on April 18.

US Orders Most Companies to Wind Down Operations in Venezuela by May

2024-04-17 - The U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control issued a new license related to Venezuela that gives companies until the end of May to wind down operations following a lack of progress on national elections.

Repsol Eyes Increasing Core US Upstream Business

2024-02-29 - Madrid-based Repsol SA will invest €$2.2 billion (US$2.38 billion) between 2024-2027 on its unconventional assets in the Marcellus and Eagle Ford as it focuses on increasing its core U.S. upstream business platform.