Developing the Permian Basin is a challenge unlike any yet encountered in the global oil industry, says Bob Peterson, a Houston-based partner in energy and utilities at Arthur D. Little Inc. (Source: G.B. Hart/Shutterstock.com)

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the February 2019 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

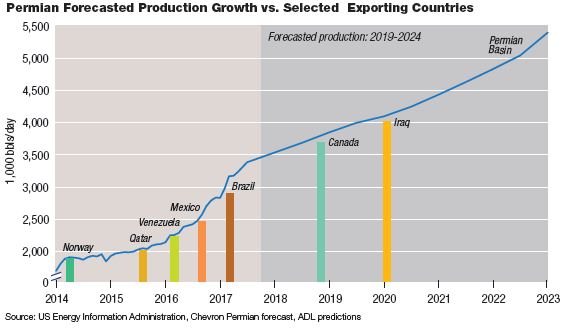

The miraculous development of U.S. shale production can be credited to innovation, well-developed infrastructure and (pre-2018) readily accessible capital markets. As a result, by 2014, U.S. tight-oil output was about 4 million barrels per day (bbl/d). And, by 2022, it’s poised to grow to 8 million bbl/d, largely from the prolific Permian Basin.

At that point, production from the Permian alone will be equivalent to that of Iraq (4.65 million bbl/d as of October 2018), the second-largest OPEC-member producer, trailing only Russia and Saudi Arabia.

Because of this dramatic increase, the U.S. has become an oil exporter, moving 2.2 million bbl/d in July, according to EIA data. Most of the new Permian oil is expected to be exported, but at what price?

U.S. independents have been largely responsible for the domestic boom to this point. To maintain their leadership position, these shale developers must consider and manage a number of complex issues.

Partnerships. Independents are just that: “independent,” specifically in terms of not operating refining and marketing assets. As a result, virtually all of these E&Ps sell their oil at the wellhead and move to the next drilling campaign. It’s a simple world but a risky one, as the U.S. becomes a major exporter and competition rises in global markets.

In this environment, the “drill, sell at the wellhead, repeat” pattern will need to change if independents want to maximize steady cash flow. They will need to exploit global markets, just as Canadian heavy-oil producers have done, with excess production.

For example, Canadian integrated Husky Energy Inc. and U.S.-based independent Devon Energy Corp. (NYSE: DVN) have a long-term deal to supply crude to Reliance Industries Ltd. in India in exchange for a slight premium to the heavy-oil price index.

For independent producers of U.S. unconventional oil, plenty of opportunities exist for supply arrangements. Mexican, Latin American and Chinese refineries are the most likely destinations.

Canadian integrated Suncor Energy Inc. (NYSE: SU), a major heavy-oil producer, offers a model to consider. It systematically builds demand-pull for its production by establishing trading and marketing offices in markets it considers attractive, such as Houston, China and Mexico.

Commanding and maintaining a price premium. Under the traditional model of selling oil at the wellhead, independents have become accustomed to success without factoring in fluctuations in regional and global markets. Those days are gone, as regional pricing spreads relative to WTI and global price spreads relative to Brent will certainly affect producers’ ability to stay predictably profitable.

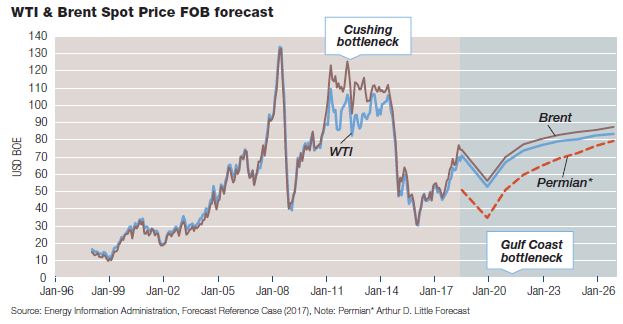

Consider the widening gap between the two primary oil-price benchmarks: WTI and Brent. Since the advent of shale, WTI has traded at a discount to Brent as steep as $10 per barrel (2011–2014), largely reflecting insufficient takeaway infrastructure for the former as North American production has ramped up.

As Permian production, in particular, now exceeds takeaway capacity once again, a separate, Permian-specific discount has arisen. This discount—as much as $25 per barrel in mid-2018 and declining to under $10 per barrel in November, as per CME Group—may persist well into 2019, dramatically affecting Permian profitability.

Independents can stay ahead of the pricing fray by identifying and establishing strategies to reduce that discount and, in some cases, realize a premium for their oil. These players will need to develop new export capacity at ports such as at Brownsville, Texas, to alleviate the growing bottlenecks at Houston and Corpus Christi, Texas.

Additionally, new, dedicated pipelines for ultra-light Delaware Basin production can allow this oil to command premium pricing, avoiding blending with lower-quality crude. Finally, independent operators with sophisticated trading capabilities can take advantage of short-term WTI pricing variations by timing puts and calls with on-demand well completions, similar to the strategy that integrated operator Shell Oil Co. is currently following.

These actions will help reduce the differential and, in some cases, result in a premium of more than $5 per barrel to Brent.

Operator collaboration. According to a recent Arthur D. Little Inc. (ADL) study, “Permian Production Constraints, 2018–2022,” more than 41,000 wells at a total capital cost of about $300 billion are planned to be drilled and completed during the next five years. The demands on infrastructure will be tremendous.

Trucks, roads, water, power and sand as well as community provisions, such as housing, schools and hospitals, are all necessary to sustain rapid development. By ADL’s calculation, about 1 million barrels of growth in daily production is at risk of in-basin infrastructure being unable to support operations.

In expensive basins, such as offshore West Africa and in the Gulf of Mexico, operators pool non-competitive services—lodging, supply boats, safety management, helicopter transportation, for example—to lower costs and improve the quality of service. Unfortunately, the “independent” nature of shale operators is a strong cultural barrier to this type of collaboration.

However, longtime independent Permian operator Pioneer Natural Resources Co. (NYSE: PXD) has initiated an effort to potentially pool power generation for the benefit of operators as well as towns and ranches. This is a good start to addressing the demand for common services, but much more will be needed.

Feeding the capital machine. While the Permian build-out requires collaboration, it also calls for a massive influx of capital. This is perhaps the greatest challenge in the basin.

To provide potential solutions, operators should think more creatively about funding structured projects. Pioneer’s power-gen scheme offers a strong example in this case, as it seeks to pool demand and provide a 20-year annuity-like return to investors, such as insurance companies, retirement funds and high-net-worth family offices.

Similar projects have already become commonplace in the pipeline space, but these practices need to expand to water management, community infrastructure, roads and transportation, for example, to enable sustainable development.

Developing the Permian is a challenge unlike any yet encountered in the global oil industry: to grow production to exceed that of any oil-exporting country other than Saudi Arabia and Russia in fewer than five years.

It is uncertain whether this challenge can be met. It demands that U.S. independents go against their nature by collaborating in key areas. It requires establishing markets, building new partnerships to a level not yet seen in the sector and giving up control of traditionally competitive capabilities to attract the necessary investment capital.

Forward-thinking players can change the way they do business, giving rise to a new ecosystem that will be able to capitalize on current opportunities and create new avenues for growth.

Bob Peterson is a Houston-based partner in energy and utilities at Arthur D. Little Inc., an international management-consulting firm with headquarters in Belgium.

Recommended Reading

Range Resources Holds Production Steady in 1Q 2024

2024-04-24 - NGLs are providing a boost for Range Resources as the company waits for natural gas demand to rebound.

Hess Midstream Increases Class A Distribution

2024-04-24 - Hess Midstream has increased its quarterly distribution per Class A share by approximately 45% since the first quarter of 2021.

Baker Hughes Awarded Saudi Pipeline Technology Contract

2024-04-23 - Baker Hughes will supply centrifugal compressors for Saudi Arabia’s new pipeline system, which aims to increase gas distribution across the kingdom and reduce carbon emissions

PrairieSky Adds $6.4MM in Mannville Royalty Interests, Reduces Debt

2024-04-23 - PrairieSky Royalty said the acquisition was funded with excess earnings from the CA$83 million (US$60.75 million) generated from operations.

Equitrans Midstream Announces Quarterly Dividends

2024-04-23 - Equitrans' dividends will be paid on May 15 to all applicable ETRN shareholders of record at the close of business on May 7.