[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the December 2020 issue of Oil and Gas Investor magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

Waha natural gas marketers, Williston Basin oil producers, Wall Street stock pickers and everyone in between will soon be glad that 2020 is over—and it’s been one for the record books.

“Considering the situation, I think we’ve come through 2020 pretty well. Our EBITDA is down about 20%, which isn’t too bad when we thought we were looking at the end of the world,” said one executive.

The price of oil has been hovering around $40/bbl for a while now. “At $40 you’re dancing on the head of a pin,” said Bryan Benoit, the national managing partner for energy at Grant Thornton. “It’s not so bad that it causes a lot of problems with redeterminations, but it’s not fantastic either. It’s not great, it’s not desirable, but it’s not going to cause an [industry] shut-down.” Benoit was announced in his new role in September, and he works on restructuring, mergers and acquisitions and technical transformations such as using data analytics.

“We see a recovery in oil and gas markets and prices in second-half 2021. Part of that is in respect to companies managing around the pandemic. There is a lot of noise in the system, but eventually you’d expect the system to move back to some normalcy.”

Benoit said his clients are concerned with cash flow and tax consulting. The best anyone can do is study everything, read voraciously and act based on experience and analysis, he advised.

The pandemic is part of “a marriage of two black swans,” said Bob McNally, president of Rapidan Energy Group, referring to the twin problems of the coronavirus and the oil price war. Speaking on a podcast, he said, “COVID-19 amounts to a black swan for demand ... a lot of demand will come back if we have a vaccine … but there may be some permanent shift [in transportation use, especially for air travel].”

After a wildly disruptive, exhausting year filled with surprising macro and micro shocks, everyone is eager to turn the calendar page to 2021 and get on with it. But what does “it” look like?

McNally said, “We are not out of the woods yet, and there is a risk that oil prices could go down next year. Oil and gas remain vulnerable to risk, and we see the need for more consolidation.”

Still, some encouraging macro signs were beginning to appear as 2020 began to wane. At press time, the uncertainty surrounding the presidential election that spooked the market looked to be over, and more important, Pfizer announced its COVID-19 vaccine appears to be 90% effective.

Fed chair Jay Powell said the housing market and business investment have recovered, but the pace of overall improvement in the U.S. economy was moderating thanks to the pandemic’s continuing spread. He said the path ahead remains uncertain. S&P Global said it doesn’t expect the U.S. economy, as measured by gross domestic product (GDP), to reach the pre-COVID-19 levels of 2019 until late next year. What’s more, this assumes Congress passes another huge stimulus bill.

Goldman Sachs said it thinks GDP will continue to suffer through first-quarter 2021 but will improve by next summer, causing a V-shaped economic recovery, with global GDP rising 6% next year from the lows seen this year.

Everyone agrees that the 2021 outlook hinges on stemming the pandemic with a widely available vaccine, which in turn will hasten the global economic recovery, and finally, improve the balance between oil and gas supply and demand.

But uncertainty still reigns. Deloitte’s consulting arm, for one, recently decided to send clients the firm’s outlook report twice a year now instead of annually because things are changing so quickly, said Duane Dickson, U.S, oil, gas and chemicals sector leader.

One of the leading indicators for demand that Dickson tracks is miles driven and airline miles flown. “We are starting to see signs of demand returning,” he told Investor. “We’ve seen some improvement, but it’s a light at the end of a pretty long tunnel. It could get bumpy in the next six months. I’ve seen a lot of different estimates out there, and most of them say we’ll be back to pre-COVID-19 oil demand levels in two years … and it could take longer.”

His advice? If a company’s survival is now assured, it cannot slip back into complacency but should continue to stay disciplined, think about partnerships or consolidation if that makes sense and not wait for a vaccine announcement.

“If you look around, a lot of companies are doing great and hitting their goals, but it depends on their balance sheet. Are they going to join forces, or tough it out? But a company has to be ready to compete once it’s done with the difficult stuff,” Dickson said.

“You know, people always say they have no time to think, so now is the time to think.”

U.S. Army Gen. George S. Patton, one of the most important Allied leaders during World War II, once said, “If everyone is thinking alike, then somebody isn’t thinking,” so maybe a few contrarian E&Ps out there will spend more in 2021 than they did in 2020.

Peter Drucker, the famed management consultant, said that thinking about possible outcomes is an important skill for every manager in turbulent times. Unfortunately, this kind of anticipation or planning is hard to do. Most people tend to react instead of anticipating. Executives in the cyclical oil and gas industry are used to going into problem-solving mode quickly, rather than operating from the stronger position of anticipating and avoiding problems from the start.

Patton also said, “Success is how high you bounce when you hit bottom.”

By most accounts, the oil and gas industry has seen the bottom. The question now is, how high can it bounce, and when? At press time, the U.S. rig count was recovering slowly. Some 300 oil and gas rigs were drilling, still down significantly from more than 800 a year ago, Baker Hughes Co. said. About 125 completion crews were working, a small improvement from the lows seen this summer.

“A gradual decline in Lower 48 output may set in from September as onshore drilling remains below the level required to maintain production in nearly all U.S. basins,” said Rystad Energy, “despite a robust fracturing exercise where operators bring on their DUC inventory.”

Rystad projects U.S. onshore production will start rising in second-half 2021 to average 10.82 MMbbl/d next year. Most E&P companies expect to proceed with caution and spend less than cash flow, even if oil and gas prices improve. Welcome to the new normal.

It might be a fool’s errand to try to predict anything concrete at this point given all the uncertainties, but we decided to survey various industry observers and consultants for their guesstimates and the reasoning underpinning their thoughts.

Who better to start with than OPEC? During a virtual conference about India sponsored by IHS Markit CERAWeek in October, OPEC Secretary General Mohammad Barkindo said the recovery may take longer than OPEC originally hoped as the pandemic was beginning to spread again. Nevertheless, OPEC “will stay the course” and not allow oil prices to plunge as they did last spring, he said.

The quota reductions it agreed to in April are set to expire in January 2021, which would restore 2 MMbbl/d to supply—unless the members of OPEC+ agree to extend the production cuts, as Russia President Vladimir Putin has hinted they might. In June OPEC production fell to a 30-year low. In the third quarter, it was around 23.8 MMbbl/d.

In October, OPEC released its 2020 version of the annual OPEC World Oil Outlook, cutting its global demand forecast for 2021 by 80,000 bbl/d.

In October, OPEC released its 2020 version of the annual OPEC World Oil Outlook, cutting its global demand forecast for 2021 by 80,000 bbl/d.

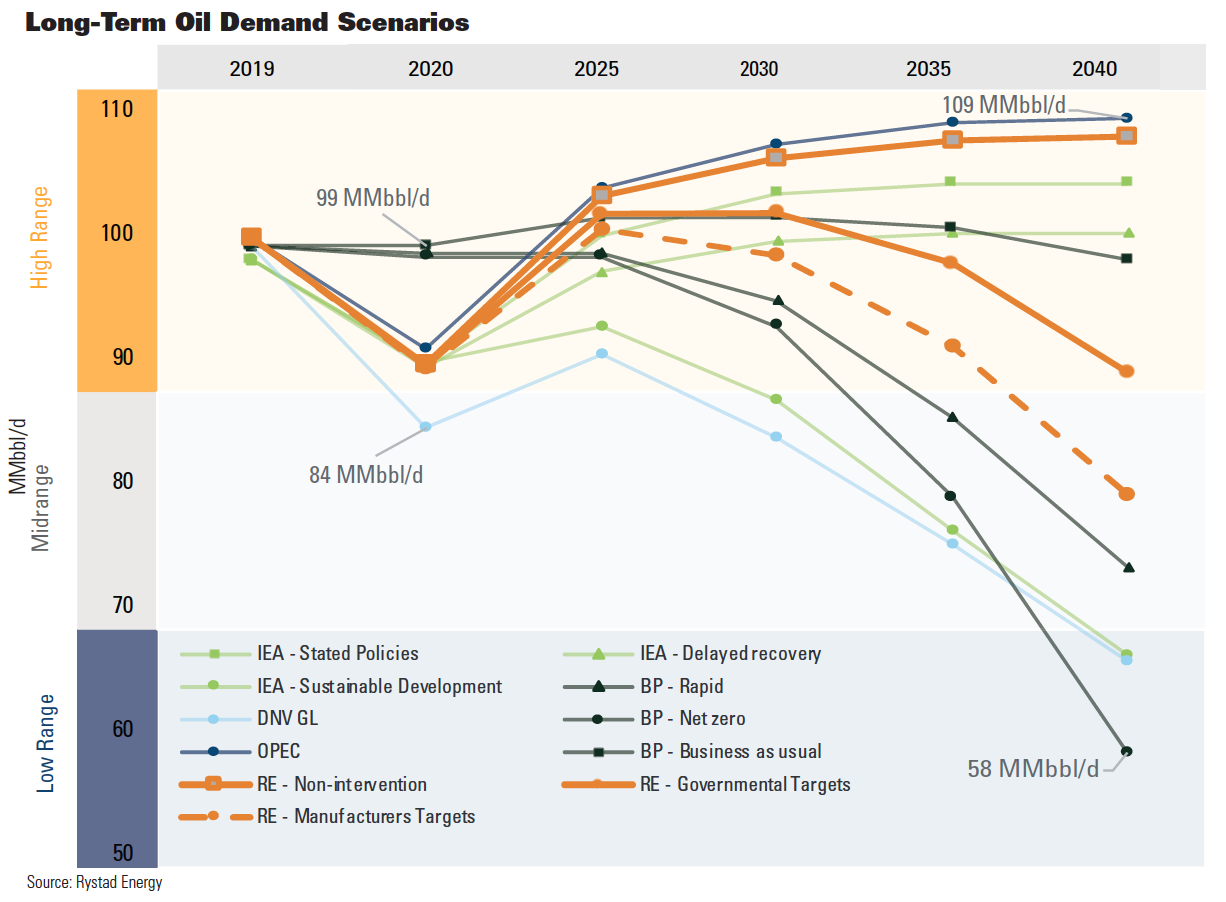

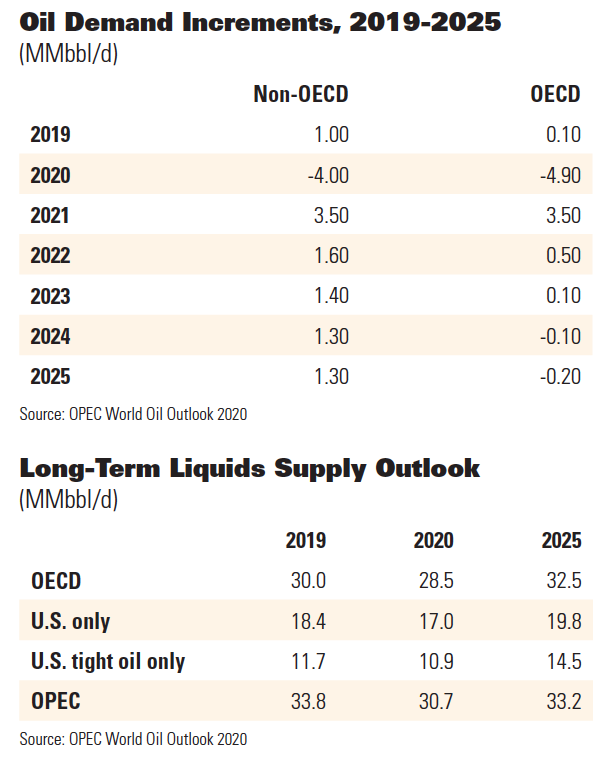

OPEC thinks a gradual global oil demand recovery will occur, with current demand maybe increasing by 6.54 MMbbl/d to reach 96.84 MMbbl/d next year. The narrator of its video presentation at the group’s website said, “Further normalization will take a couple of years. The long-term energy outlook was uncertain even before the pandemic.”

It foresees a faster period of “catch-up” for the hardest hit sectors such as aviation and road transportation, and especially in the regions that were most affected by the pandemic shutdowns. GDP includes more factors than transportation and oil demand, of course. To that end, the group said the average growth rate of GDP has slowed in the OECD countries. It is now forecasting it to be 0.7% per year from 2019 to 2025, instead of the pre-COVID-19 estimate of 2.1%.

In 2019, global oil demand had reached a high of nearly 100 MMbbl/d. In 2020, global demand fell by about 9 MMbbl/d, an unprecedented disaster for the industry. OPEC’s outlook, however, now indicates that in 2021, demand will recover almost 7 MMbbl/d of that total (some 3.5 MMbbl/d in each of the OECD and non-OECD countries).

The pace of demand growth will then slow in 2022 but regain another 2.1 MMbbl/d, the OPEC outlook said.

Longer term, it forecasts demand to climb to 102.5 MMbbl/d in 2024 and then to 103.7 MM-bbl/d in 2025. Combine that need for more oil with the natural production declines occurring, and you have a recipe for more investment in drilling in the next five years. (OPEC said it still believes demand will plateau in the second half of the 2040s.)

Supply concerns

What about supply, the other half of the balance equation? OPEC is clear, as it always has been, that it can and will produce enough oil to fill any supply gaps that might occur. It aggressively cut production by 7.7 MMbbl/d to 5.7MMbbl/d as soon as the implications of the worldwide economic shutdown became apparent in March.

That is slowly changing now.

Mizuho Securities director of energy futures Robert Yawger said in a report, “Between the U.S. and Libya, production is up almost 2 MMbbl/d [during two weeks in October]. OPEC+ is scheduled to add 2 MMbbl/d to the market in January. OPEC+ has promised to monitor the situation and make adjustments accordingly.”

Yawger said he had thought OPEC+ would gradually layer in its additional production during 2021, or even delay it a few months, but if its members see U.S. tight oil production rising again and stealing market share, they might make an about-face and “let the chips fall where they may … most likely with crude oil down considerably.”

In the U.S. and other non-OPEC nations, production is rising. “Following an expected sharp decline of 3.3 MMbbl/d in 2020, its first annual decrease since 2016, non-OPEC liquids supply will grow modestly in 2021 and pick up momentum in the following years, thus increasing from 65 MMbbl/d in 2019 to 70.7 MMbl/d in 2025,” OPEC said.

The medium-term growth in oil output will be led by Brazil, tight oil plays in the U.S. and production increases in Norway, Ghana and Kazakhstan. OPEC said U.S. tight oil supply will grow until around 2030, but not as much as previously expected, with OPEC making up the difference.

On an annual average basis, EIA expects U.S. crude oil production to fall from 12.2 MMbbl/d in 2019 to 11.4 MMbbl/d in 2020 and 11.1 MMbbl/d in 2021.

Libya announced its production would rise to 1.3 MMbbl/d by year-end 2020, after falling to about half that earlier this year. In addition to additional barrels from Libya and the U.S., the industry faces possible additional supply from Iran, depending on what transpires when President-elect Biden renegotiates the Iran nuclear treaty, effectively enabling that country to increase supply.

ABN AMRO Bank NV’s chief economist, Hans van Cleef, said in a report right before the election, “Biden will pursue a different policy toward Iran (renegotiating a nuclear deal that will go hand in hand with lowering sanctions against Iran), and reconsider relations with Russia, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Mexico, among others. As these are all oil-producing countries, this could have an impact on the oil trade, and therefore on oil prices.”

Mobility adds demand

The tone of 2021 hinges on more than the standard factors that industry is used to analyzing such as OPEC decisions and capital flows. A recent Bernstein Research report put it succinctly: “The most obvious near-term catalyst for the sector remains a successful vaccine for COVID-19, which restores mobility and economic growth.”

Mobility does appear to be recovering slowly, an important point for determining global oil demand trends. In late October, for the first time since the pandemic shut down aviation in March, the Transportation Security Administration processed 1 million passengers in a single day at the nation’s airports. That’s progress, but the number is still down significantly from the same time a year ago.

In BP’s recent Energy Outlook 2020 edition, the company presented three scenarios for the industry’s long-term future. Road and air travel increase in all three. But, it also noted that the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have a persistent impact on the global economy and energy system, with global GDP likely slow to recover or be lower, especially in the emerging economies like India, Brazil and Africa, whose oil demand growth the industry has counted on heretofore.

[SIDEBAR]

The Midstream Take

Bill Ward is senior vice president of commercial for Tulsa’s Superior Pipeline Co. LLC. But he has an even wider view of the world because he also chairs the GPA Midstream Association. Ward has been calling his member CEOs for their perspective on that sector and the way forward.

“A lot of them said they’ve pretty much made it through the storm, but it was quite a storm,” he told Investor. “I’m somewhat positive for 2021. I feel 50-50 that we’re on an even keel now, with no more rough seas. But I’m not saying we don’t still have challenges.”

Because the midstream sector relies on active drilling for sustained throughput, it has been hurt as drilling and production declined, and there is an overbuilt situation now in the processing end, he said.

“I think consolidation will be a real factor in 2021. You’re already seeing this in the upstream, and I think the next phase is in midstream. We’ve got too many fractionating plants.”

Ward also said some consolidation ideas that were being pursued earlier this year came to a halt once the downturn began and valuations changed.

Spending’s new normal

Disciplined spending is a mainstay of 2020 that will continue throughout 2021 as part of the new normal. For example, a Cowen & Co. report showed that in aggregate for the 45 E&Ps it follows, spending would be down another 7% from the low levels of 2020, which had plummeted 48% from 2019. Cost reductions are helping E&Ps to manage with oil prices below $45/bbl.

Industry bellwether EOG Resources Inc. said that at $36 WTI, it can fund maintenance capital for holding production flat in 2021 and still pay the dividend as well. Murphy Oil Corp. said its program for 2021 is targeting a flat production profile with capital spending consistent with FY2020 (about $700 million).

Marathon Oil Corp. said it will spend no more than 70% to 80% of cash flow and hold production flat with its fourth-quarter level, if oil remains between $40 and $45/bbl. Its 2020 budget of $1.2 billion may drop to $1 billion in 2021.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) seems to be worried about these levels of spending. It estimated that energy demand might fall by 5% in 2020 when the final tally is in—with oil and coal taking the biggest hits. Offsetting the oil demand loss, however, is the fact that drilling and completions around the world are down, putting a damper on production growth, especially in the U.S. shale plays that decline so rapidly in the first place.

“Investment in energy … falls by 18%, driven by a contraction in investment for oil and gas. If the COVID-19 crisis lasts for several years, this investment cut might fit a more subdued demand environment. If the world takes bolder action on climate change, those cuts might also seem prudent,” said Nikos Tsafos, a senior fellow with the Energy Security and Climate Change Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

“But these investment curtailments could also cause a price spike in the near to medium term, raising concerns about energy security but also changing consumer attitudes about alternative products and services,” Tsafos said. “The IEA numbers on investment are a reminder that no matter what trajectory we are on, we might still encounter bumps along the way. We doubt that OPEC will raise supply to accelerate production of stranded oil assets and instead will strive to keep oil prices in a reasonable range.

“OPEC currently produces about 25 MM-bbl/d with an effective capacity of about 32 MMbbl/d. Over the past decade, OPEC effective capacity has averaged 30- to 35 MMbbl/d. While the return of Iran could raise OPEC effective capacity by another 3 MMbbl/d, we doubt that other OPEC members will try to accelerate production of stranded oil reserves through growing capacity. Large budget deficits and the implosion of prices mean that this would be a painful and high-risk strategy.”

Oil price forecasts

Most observers expect oil prices to rise in 2021 due to a confluence of factors: rising demand, (albeit more slowly than the industry would like), flattish supply and less oil in storage. “At [oil] futures strip pricing, we forecast hefty global inventory draws in both 2021 and 2022. The industry will ultimately need pricing much higher than the current strip,” said investment bank Raymond James in an October report.

“After broadly flattish prices in 4Q20 and 1Q21, reflecting [near-term headwinds such as COVID-19 and the global economic recovery], we maintain our forecast for a 2021 exit rate of $70/bbl WTI, equating to a full-year 2021 average of $55, which is about 30% above the strip.”

The International Monetary Fund said it assumes oil will average $46.70/bbl next year, with demand recovery the main factor.

Natural gas stars

There is potential this winter to see the tightest natural gas market in the past decade, according to Morgan Stanley, which forecast $3.25/MMbtu in 2021. Part of the reason is that gas associated with Permian oil drilling has declined and LNG exports are picking up again.

The Lower 48 natural gas outlook is bright based on tight supply-demand fundamentals, and this was highlighted by the fact that in October the NYMEX strip price rose above $3/MMcf about a month earlier than usual as the winter heating season approached. However, a warm winter is predicted.

One group that must watch all this very closely is the marketing department at Range Resources Inc., since the company is among the top 10 gas producers in the U.S., making 2.2 Bcf/d. It is among the top five NGL producers as well, and it has a multidecade well inventory in the Appalachian Basin.

“We are thrilled with the way the natural gas and NGL markets are setting up as we go into this winter and into 2021,” said Laith Sando, head of investor relations, during a presentation to the Energy Prospectus Group in Houston in October. He was joined by two colleagues who gave all the details on why they are optimistic.

Supply is down over the past year more than demand is down, on a percentage basis, explained Ben Stanton, Range’s director of energy commodities and market analysis. And the natural gas rig count is down about 60% from early 2019. The drilling rig counts in the Appalachian Basin and the Haynesville Shale are now below the amount needed to hold gas production flat in those plays.

“You really need a price of $3 to deliver medium-term supply growth,” he said, noting that growth is not the main goal anymore—most E&P companies have vowed to set their budgets at 70% to 80% of cash flow to limit growth or keep production flat.

“We’ve had double black swan events, with the COVID-19 pandemic and the price war that started between the Russians and Saudis, so there’s been a lot of decline in associated gas from oil wells as oil completions are down.”

Even Continental Resources Inc., best known as a big oil producer and export champion, may be pivoting to focus on natural gas. Looking for stronger gas fundamentals in 2021, it shifted some Oklahoma rigs to gassy areas in second-quarter 2020. Two-thirds of its hedges have an average floor price of $2.67 and a weighted average ceiling price of $3.44.

Lower rig counts and fewer well completions around the country in 2020 caused observers to lower their production forecasts, especially for Permian Basin natural gas flows for the next couple of years. But new infrastructure concerns at Waha in West Texas will tighten the price difference between that and Henry Hub. New pipelines coming on in 2021 may end up “stealing” gas from existing pipes. On tap are Kinder Morgan’s Permian Highway (2.1 Bcf/d capacity, going to Houston) and the Whistler Pipeline (2 Bcf/d to Corpus Christi). RBN Energy’s latest mid-case scenario calls for flat Henry Hub gas prices through 2025 at about $2.50/MMBtu and assuming $45 oil.

How will that affect production? At the end of the third quarter, the Permian Basin’s gas output was averaging 11.5 Bcf/d, with RBN Energy predicting that it would rise slightly to 11.9 Bcf/d next year, but on up to 12.3 Bcf/d in 2022.

“It’s a far cry from the last three years when the Permian averaged about 2 Bcf/d of growth every year,” the firm said in an October update.

Rystad Energy revised upward its dry gas production forecast for 2021 by another 500 MMcf/d, saying the most significant additions will be thanks to “a more resilient base decline in gas basins.” It said that in the Appalachian region, there are “still significant numbers of older wells that produce at restricted rates, and these wells might make a positive contribution of up to 600 to 700 MMcfd to base production in the next three to four quarters.”

Even with this additional supply in 2021 compared to the firm’s previous outlook, “The U.S. domestic gas market is still heading toward a structural supply deficit, with the possibility of stronger domestic gas prices if the global gas market recovers further,” the firm said in September.

[SIDEBAR]

OFS Channel Checks

Polling the oilfield service (OFS) companies reveals good insights into what can be expected as 2021 unfolds, given that they analyze closely their E&P customers’ many needs. And the OFS companies are hoping for an activity rebound to recover from a disastrous year in which the U.S. rig count fell below 300. Analysts remain cautious.

“E&P companies want to spend more; their production is declining,” said James West, OFS analyst at Evercore ISI in New York. “So, we think North American spending will be up and, internationally, in the low double digits. International, both onshore and offshore, picks up the slack. My general view is that while we see an improving environment for OFS, we are at 2006 levels of capex globally now, which is unsustainable.

“We think we’ll see oil at $100 by the end of 2021 and oil markets will tighten on expectations of that. We do not think the North American market will be the same size as pre-pandemic levels in terms of production and service activity. We don’t see a market—not until 2022—where we have 450 to 500 rigs and 150 to 200 frac spreads, and that would be down from the 2019 peak. The U.S. shales will be much less active going forward.”

Jacob Lundberg, oilfield analyst at Credit Suisse in New York, told Investor in November via an email, “We remain cautious on the U.S. oil services complex.”

He expects to see an activity recovery in 1H21 that continues through the year, a hopeful sign that was already under way with the U.S. onshore rig count average in the fourth quarter up 12% vs. the 3Q20 average (through November 6).

“However, we expect pricing for the most part to remain under pressure. Activity is recovering to a ‘new normal,’ but that new normal is about 50% below recent activity levels, in our view,” Lundberg said. “In that environment, we see little opportunity for the U.S. oil services complex to gain pricing power. Recent pressure on oil prices is clearly not helpful and plenty of downside risks remain (e.g., COVID-19 lockdowns).”

In a separate report, he cited data showing that as of early November, the year-to-date number of well permits in the Gulf of Mexico stood at 125, versus 193 last year at the same time, for a 35% decrease.

Onshore drilling began picking up this past summer and through the fall after plummeting in the spring, although it was still at a cautious level. In the next few months, however, activity could rebound substantially just from completing the nearly 7,600 DUCs, as per the latest EIA data. The nation’s hydraulic fracturing fleet is slowly getting back to work, sitting at 127 at press time. Then too, as the new year begins, E&P companies will be working on fresh budgets.

Evercore’s West noted that the service companies have abandoned growth in favor of returns, and they are operating more like an industrial company model.

“If you’re an E&P executive, your belief is that service pricing has probably bottomed, but there may not be much inflation until the back half of 2021, as more assets are retired. And just like in the E&P space, we have some big M&A underway that should start to accelerate.

“A lot of product lines have 30 or 40 participants, and that’s too many.”

The firm sees $45 Brent oil price now and $50 next year, reaching $55 by year-end 2021. But for natural gas, the call is for $2 or $3 per thousand cubic feet for the foreseeable future.

And about those calls with service companies? Evercore also covers biotech. “Demand is tied to having a vaccine so that the economy gets back to normal.” West said the firm feels good about the prospects for an efficacious vaccine, after talking to the biotech analysts. “We are upbeat about that, and that should help drive demand.”

Recommended Reading

EQT Deal to ‘Vertically Integrate’ Equitrans Faces Steep Challenges

2024-03-11 - EQT Corp. plans to acquire Equitrans Midstream with $5.5 billion equity, but will assume debt of $7.6 billion or more in the process, while likely facing intense regulatory scrutiny.

EQT Ups Stake in Appalachia Gas Gathering Assets for $205MM

2024-02-14 - EQT Corp. inked upstream and midstream M&A in the fourth quarter—and the Appalachia gas giant is looking to ink more deals this year.

EQT Strengthens Appalachian Position in Swap with Equinor

2024-04-16 - EQT, the largest natural gas producer in the U.S., is taking greater control of the production chain with its latest move.

EQT, Equitrans to Merge in $5.45B Deal, Continuing Industry Consolidation

2024-03-11 - The deal reunites Equitrans Midstream Corp. with EQT in an all-stock deal that pays a roughly 12% premium for the infrastructure company.

EQT, Equinor Agree to Massive Appalachia Acreage Swap

2024-04-15 - Equinor will part with its operated assets in the Marcellus and Utica Shale and pay $500 million to EQT in exchange for 40% of EQT’s non-operated assets in the Northern Marcellus Shale.