Private-equity players secured multibillion-dollar acquisitions in less-volatile infrastructure plays last year,a trend that has continued this year. Photo Courtesy of Tallgrass Energy LP.

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the April 2020 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

Dealmakers in the midstream sector had a busy 2019, and there are indications that the trend could continue this year. Like the E&P sector, midstream companies have increasingly faced headwinds from the investment community due to perceived lop-sidedness in the risk/reward equation. This squeeze, paired with other financial factors such as limited interest from the debt markets, has resulted in depleted coffers that have partially hamstrung growth prospects. As a result, private money has moved into the sector and may fuel additional deals going forward.

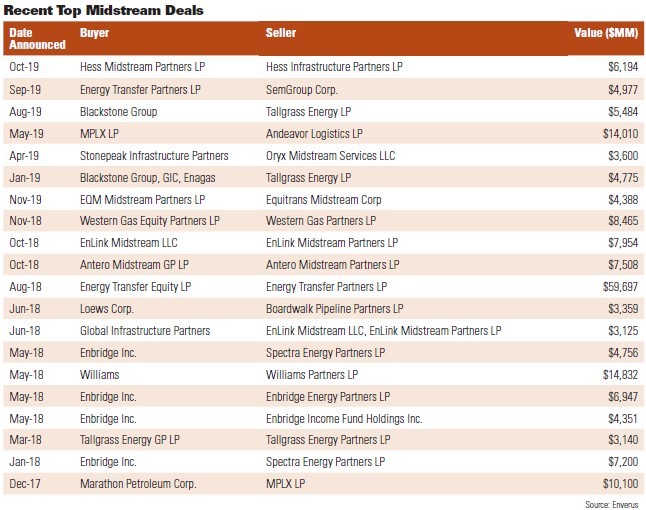

According to S&P Global, midstream acquisition deal values almost doubled to $27.8 billion in the first five months of 2019 compared to the same period the previous year. The movers in the space were mostly private-equity concerns looking to secure positions in the less-volatile infrastructure plays required to move record amounts of production out of places like the Permian and Eagle Ford basins in Texas.

Blackstone Infrastructure Partners LP’s multibillion-dollar pursuit of Tallgrass Energy LP netted the company’s private portfolio a growth-oriented midstream energy company specializing in moving oil and gas from the Rocky Mountains and the upper Midwestern and Appalachian regions into major demand markets. Stonepeak Infrastructure Partners, an infrastructure-focused, private-equity firm with over $15 billion of assets under management, snapped up Oryx Midstream Services LLC for $3.6 billion. The deal covered a robust pipeline network in the Permian.

“I think midstream M&A has to be viewed in the context of the infrastructure build cycle,” said David Amoss, midstream research analyst with Heikkinen Energy Advisors LLC. “We’re sort of on the down slope of that cycle now. If you went back a couple of years, you had significant capital spending ahead of the industry to unlock the Permian growth, to change the routes from other regions to new delivery points, specifically to move to a more export-driven delivery. That money has now largely been spent.

“We were pretty tight—there was a high utilization of midstream assets even in ’18 and ’19. A lot of those ‘tight’ situations are being unlocked now. Long-haul crude pipe, long-haul NGL pipe, fractionation, processing—all of those asset classes are moving into a situation with less average utilization and more excess capacity,” Amoss said. “I think that really changes the dynamic of how M&A will occur in the future, but I do think this year and next year will be robust M&A years in the midstream sector.”

Eight weeks into 2020, there had already been a quintet of deals in the midstream sector valued at over $1.3 billion, including Kinder Morgan Inc.’s decision to sell its entire stake in Pembina Pipeline and Phillips 66 Partners’ buy-in of Liberty Pipeline—a $1.6 billion project to transport Rockies and Bakken crude oil production to Oklahoma’s Cushing hub.

“From our conversations, midstream is the overwhelming preference for investors as opposed to upstream,” said Brendan Matthews, director with PJ Solomon. “Financial sponsors are hearing the same refrain from LPs that public companies are hearing from investors as they look to fundraise—capital is no longer there, or limited, until we receive something from our previous investments in return.

“Private-equity midstream activity has been constrained in large part due to its close association with its upstream counterparts. Upstream activity has been nonexistent, and some sponsors have been forced to bring their midstream assets to market in order to return capital to investors and help with current fundraising efforts,” he continued.

seeing intra-fund

private equity

consolidation,

but would expect

to see a bit more

collaboration

and cooperation

inter-fund

going forward,”

said Brendan

Matthews,

director with

PJ Solomon.

“Many of these midstream assets are a bit premature and would historically be billion-dollar enterprises. Where these midstream assets currently stand is a fraction of that because they don’t have the growth once associated with them—the funds will not commit to a drilling program on the upstream side in order to maximize value for the midstream asset. I think it’s interesting that you’re seeing the same pressure applied to the private side is on the public side.”

Strategic drivers

For 2020, midstream M&A is positioned to be more strategic in nature. Going back to the middle of the last decade, companies raised a lot of private-equity capital in the energy space. This capital formation was then put to work in what became a very competitive environment.

In areas like the Permian, which saw a large amount of investment, contractual support for the assets that were created was weaker than it had been historically. That has made it difficult for private-equity companies to find their exit, as a lot of those assets and funds cannot currently achieve the returns their investors and sponsors once thought possible.

“Private-equity capital that was deployed during that period now has two options,” said Amoss. “One is you wait out the cycle; you wait for a period of time where you’re not selling into an underutilized asset market. And in many cases the private-equity assets are more underutilized than the public assets are. You wait out that cycle or, secondly, you just take a lower return than you used to originally underwrite your fund. I don’t think either of those are particularly great options, but I do think there’s enough assets that are in that category that some of them will be forced to move here.”

A traditional driver of midstream M&A has been upstream companies selling off midstream assets to raise capital; however, many of those deals have already been done and not a lot of strategic offerings exist beyond those controlled by the larger, integrated companies that don’t react to shorter-term cycles the same way that smaller operators do. Exxon Mobil Corp., Chevron Corp. and the like would not fall into the class of ‘forced’ sellers. They typically do not sell off assets just to fund other projects.

“Your forced sellers of assets who need to raise capital, and currently do not have other options, are going to get less than they would prefer or have grown to expect,” Amoss continued. “Historical M&A values won’t hold up for these assets. Those upstream companies are going to continue to market their remaining midstream assets, and they’ll just get bids that are lower than they expected. Then it’s up to their discretion or their specific situation whether or not they execute. I think a lot of higher-dollar transactions will be driven by buyers that are larger, diversified midstream companies that have existing systems that can bolt on in a strategic fashion.

“We saw a deal recently from Plains All American, which has a great oil transportation system, and they bought a gathering system in the Permian to feed that system. The economics of that system on its own probably doesn’t support a deal like that, but Plains can move those volumes through their long-haul pipelines and into their downstream network. They can make a higher return because of the system they already have. That’s the type of M&A I’d expect to see really heat up here. That will be driven by large diversified companies like Kinder [Morgan], Enterprise, Plains [and] Magellan.”

Any lack of midstream deal activity may have as much to do with the current health of the upstream sector. In years past, deals in areas such as the Permian were done when a buyer saw a climbing rig count, capital dollars being spent, type curves were being exceeded on a consistent, repeatable basis and returns were achieved. That is not the world we live in today.

“Across the board, capital budgets are falling, rig counts are dropping and companies are now required to do more with less,” said Matthews. “This shift in operator focus will have a dramatic impact on many of those in the market as they look for potential solutions, particularly those on the private-equity side.

“We are already seeing intra-fund private-equity consolidation (Jamco/Smashco), but would expect to see a bit more collaboration and cooperation inter-fund going forward.

are we’re

probably going to

start seeing some

transactions on

the water side

of things,” said

David Smith,

senior vice

president of

Mercer Capital.

“This has historically been a social impossibility, but the stance that we’ve seen some take is, ‘Hey, I probably can’t make it alone. Long term, you probably can’t make it alone. Perhaps if we get together, we have a better shot of getting us out of where we are today.’”

The bid/ask spread on many current deals is wide, but expected to narrow over time. The gap is expected to close because the ask comes down, not because the bid goes up. A litany of factors is aligning to impact the oil and gas industry in 2020—closed bank markets, the rise of environmental, social and governance requirements, global economic health (China and coronavirus) and the upcoming presidential election to name a few.

Water transactions

One area expected to emerge as a robust M&A target for 2020 is the water sector. In West Texas, for example, the growing water industry is highly fragmented consisting of several mid- to small players. Consolidation in that market is expected over the coming months.

“We have effectively witnessed a modern day land-grab arms race on the water side of the midstream sector,” said Matthews. “What was once a niche part of the business and market has become a major influencer in how operators do business. We are able to highlight our abilities relating to recycling, treatment, etc., in order to attract a new pool of investors to the space.”

“All indications are we’re probably going to start seeing some transactions on the water side of things, whether it’s supplying water to the site or the disposal business,” added David Smith, senior vice president at valuations firm Mercer Capital. “That’s the one area that has had rumblings of transactions due to a natural economics-driven consolidation, because it’s been so fragmented up to this point. It’s a newer area. It’s scattered. It’s due for consolidation and in West Texas with both a lack of water and all the fracking going on that uses a heck of a lot of water, it is ripe for that type of consolidation."

Recommended Reading

PHX Minerals’ Borrowing Base Reaffirmed

2024-04-19 - PHX Minerals said the company’s credit facility was extended through Sept. 1, 2028.

SLB’s ChampionX Acquisition Key to Production Recovery Market

2024-04-19 - During a quarterly earnings call, SLB CEO Olivier Le Peuch highlighted the production recovery market as a key part of the company’s growth strategy.

BP Restructures, Reduces Executive Team to 10

2024-04-18 - BP said the organizational changes will reduce duplication and reporting line complexity.

Matador Resources Announces Quarterly Cash Dividend

2024-04-18 - Matador Resources’ dividend is payable on June 7 to shareholders of record by May 17.

EQT Declares Quarterly Dividend

2024-04-18 - EQT Corp.’s dividend is payable June 1 to shareholders of record by May 8.