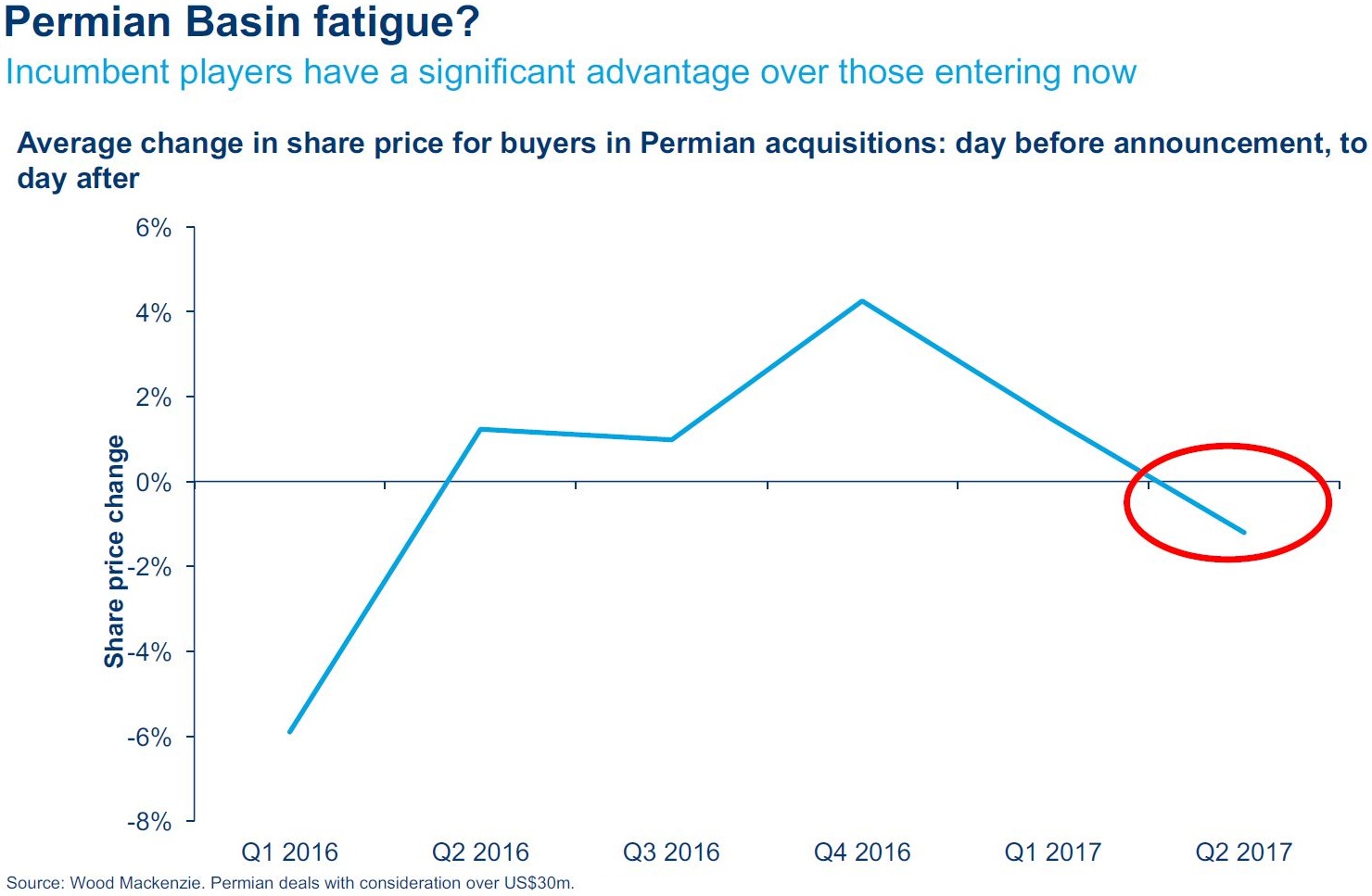

While Permian deals provided uplift to many stocks last year, 2017 has seen that trend upended with share prices falling the day after a deal is announced—sometimes dramatically. (Source: Hart Energy)

Buying a ticket to Permian Basin production—already an expensive proposition last year—now carries an additional surcharge in 2017—investors’ ire.

Producers spent nearly $27 billion in the Permian from April 2016 through July 2017, according to Moody’s Investors Service. E&Ps have primarily targeted the Midland Basin’s Martin, Glasscock, Howard and Reagan counties and the Delaware Basin’s Reeves, Pecos and Ward counties in West Texas.

In 2016, a Delaware deal could seemingly do no wrong, Robert Clarke, Wood Mackenzie’s research director for Lower 48 upstream, said at Hart Energy’s recent DUG Midcontinent Conference & Exhibition. E&P stocks generally saw a lift as high as 4% the day after a deal announcement.

“There seems to be a mood change now,” Clarke said. “Transactions no longer lift stocks. Now that’s dropped to a negative.”

Increasingly, initial market reaction to some deals sends investors skittering. Investors appear to want tighter-run E&P ships with less deficit spending and lower leverage. Companies fitting that profile see their share price rewarded, Subash Chandra, an analyst at Guggenheim Securities LLC, said at DUG Midcontinent.

“We see it [in] the stock performance, we see it in the variance in stocks. We see it in the lack of correlation with commodity prices,” he said. “The peril is clear and present.”

That peril may extend even to Permian deals, which in 2016 bolstered companies enough to be used as launch pads for public equity offerings.

Wall Street financed billions of dollars in transactions because oil prices made sense, Chandra said. The hiccup was that oil production didn’t decrease as much as expected.

In a period of excess production—rather than expected scarcity—exports have become a safety valve and “all of a sudden free cash flow is important,” Chandra said.

And Permian deals, whether due to stagnant prices, funding mechanisms or acreage costs can leave a company sucking wind.

‘Permian Fatigue?’

Clarke said the market may be suffering a case of “Permian fatigue.”

Last year, Wall Street financed billions of dollars in transactions because oil prices were “constructive,” Chandra said. E&Ps were restocking after two years without any exploration.

“Really, the main criteria was inventorial renewal and those transactions were premised on location counts based on horizontal and vertical spacing.” Then, oil prices “triple dipped … and that’s what changed everything,” he said.

Clarke noted that large-scale transactions by EOG Resources Inc. (NYSE: EOG) and ExxonMobil Corp. (NYSE: XOM) have altered the development outlook of the Permian.

But in 2017, that fairy-tale market ending has turned into a cautionary tale.

On Aug. 2, Concho Resources Inc. (NYSE: CXO) announced a $600 million Midland acquisition. That day, Concho stock traded at $128.66. On Aug. 3, the company’s stock price tumbled 8.7% to $117.46. The stock recovered in late September, more than 50 days later.

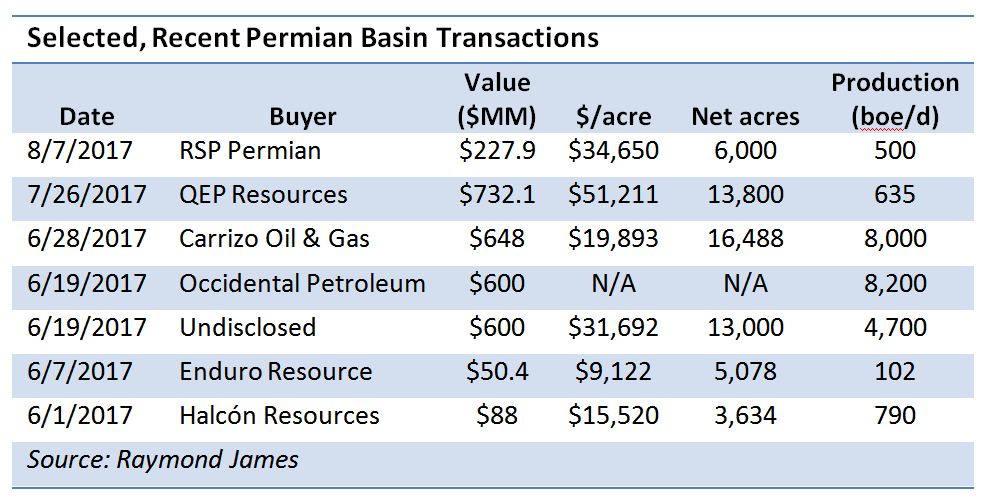

In QEP Resources Inc.’s (NYSE: QEP) case, the company spent $732 million for Midland acreage on July 26. The day after its Midland deal announcement, QEP’s share prices fell to $7.93, a drop of 14% from its previous close of $9.27.

That was despite a July 24 deal announced by QEP to divest its Pinedale assets for $740 million. The transaction was structured as a like-kind exchange for the Midland assets—allowing the company to defer income taxes on the Pinedale sale.

Moody’s Investors Service noted that the possibilities for propping up capex to the company, which had been credit positive, were reversed with the Midland deal. Instead, the company would use debt to fund operations, wrote Arvinder Saluja, a senior analyst at Moody’s.

“The company’s expected negative free cash flow will be funded through revolver borrowings and cash from operations, which was expected prior to the Pinedale divestiture,” Saluja wrote in a July 31 report.

Further, QEP was left reliant on revolver borrowings to fund its drilling and completion budget through 2018, Saluja said. “Negative free cash flow will be further strained, as we expect the company to increase its 2018 capital spending budget to develop the acquired acreage.”

The Profound Change

The E&P sector has seen profound changes since 2016 when U.S. producers were in full inventory renewal mode and transactions were welcomed by the market, Chandra said.

Even the IPO market was primed because “we were short on opportunity. Two years of no exploration yet two years of vast depletion and that’s because oil production didn’t go down very much.”

The result is two-fold. First, rare companies with free cash flow are performing best in the market, followed by companies with the least overspend. Companies with serious overspending and debt are punished.

Chandra expected the trend to reverse at some point during the year, yet through August “that relationship actually deepened,” he said.

“Those that were outspending the least were absolutely outperforming everybody else,” he said.

Goldman Sachs analysts said they recently met with E&P management teams in Houston and Dallas, according to a Sept. 28 report by Brian E. Kinsella and others.

“The theme of E&P discipline resonated, but healthy skepticism remains,” Kinsella said. “E&P management teams spanning varying sizes and basins all seemed to sing the same tune of a renewed focus on cost structure, a more measured approach to growth (some within or closer to cash flow) and shareholder returns.”

That’s been the loudest theme in the downturn, but also in prior ones.

“Many are still hesitant to believe that there has been a sea change in behavior,” the report said.

For E&Ps in the Stack and Delaware—and all other plays—the least common denominator for success appears to be a $50 per barrel price.

“$50 oil matters a lot for the next years,” Clarke said.

By 2021, non-OPEC decline rates will be a driving force in total supply volumes. For now, short-term factors have frozen supply reductions at 5%, he said.

Declines are fixed, in part, because of the industry’s talent for implementing “self-help measures” to boost cash flow—particularly maximizing output by fine-tuning production. The result is Lower 48 volumes that have held steady.

To complicate the production picture, companies, including majors, are reducing capex and directing more money to short-cycle projects with the highest returns.

“We have gas stocks trading below NAV,” Chandra said. “Which means the value of future resources is not being credited by the Street.”

The irony, Chandra said, is “we haven’t heard anything that the future of oil isn’t the future of gas.”

Wood Mackenzie’s forecast for oil prices offers little cheer. The firm expects the price per barrel to appreciate by just $1 during each of the next three years.

Darren Barbee can be reached at dbarbee@hartenergy.com.

Recommended Reading

US Drillers Add Oil, Gas Rigs for First Time in Five Weeks

2024-04-19 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, rose by two to 619 in the week to April 19.

Strike Energy Updates 3D Seismic Acquisition in Perth Basin

2024-04-19 - Strike Energy completed its 3D seismic acquisition of Ocean Hill on schedule and under budget, the company said.

Santos’ Pikka Phase 1 in Alaska to Deliver First Oil by 2026

2024-04-18 - Australia's Santos expects first oil to flow from the 80,000 bbl/d Pikka Phase 1 project in Alaska by 2026, diversifying Santos' portfolio and reducing geographic concentration risk.

Iraq to Seek Bids for Oil, Gas Contracts April 27

2024-04-18 - Iraq will auction 30 new oil and gas projects in two licensing rounds distributed across the country.

Vår Energi Hits Oil with Ringhorne North

2024-04-17 - Vår Energi’s North Sea discovery de-risks drilling prospects in the area and could be tied back to Balder area infrastructure.