Burning excess natural gas is a common practice among some operators when prices deem it uneconomic to transport gas to market. (Source: Shutterstock.com)

Neither size, geographical footprint nor classification as an independent or integrated matter when it comes to reducing the amount of natural gas flared. It comes down to governance and leadership from the board room to the field, commitment and best-in-class practices, according to a recent study by Gaffney, Cline & Associates.

The research on how leading Permian Basin operators are keeping flaring levels in check, prepared on behalf of the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), puts the practices of Chevron Corp., EOG Resources Inc., Occidental Petroleum Corp., Parsley Energy Inc. and Pioneer Natural Resources Co. in the spotlight. The companies have natural gas flaring rates ranging from less than 1% to 2.6% in the Permian Basin, which is below the basin’s average of 3.7%.

“The silver bullet is to sell your gas. If your gas is going to sales, the dilemma on how to manage flaring goes away,” said Jennifer Stewart, carbon management strategy and policy lead for Gaffney Cline. “That’s not a one and done situation. That’s not an easy strategic leadership decision to make. It takes a lot of work and a lot of commitment. But these five companies have done it.”

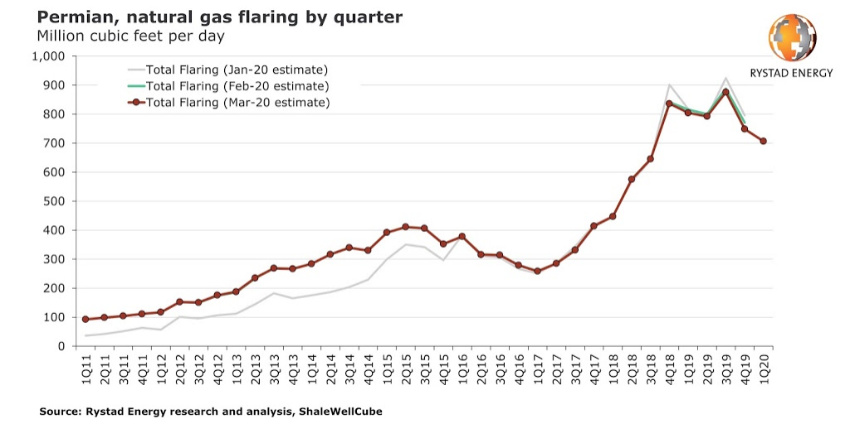

The words, spoken during a recent webinar hosted by Rice University’s Baker Institute, came as natural gas flaring from the biggest oil field in the U.S. dips as operators slow activity amid weak prices. In recent years, the Permian has become notorious for its high flaring rates, which increased as producers—seeking oil—drove production to highs.

Reducing flaring requires commitment by companies to hook up gas wells only when infrastructure takeaway is in place; however, there must also be a willingness to shut in wells when infrastructure is not available, Stewart said.

Best Practices

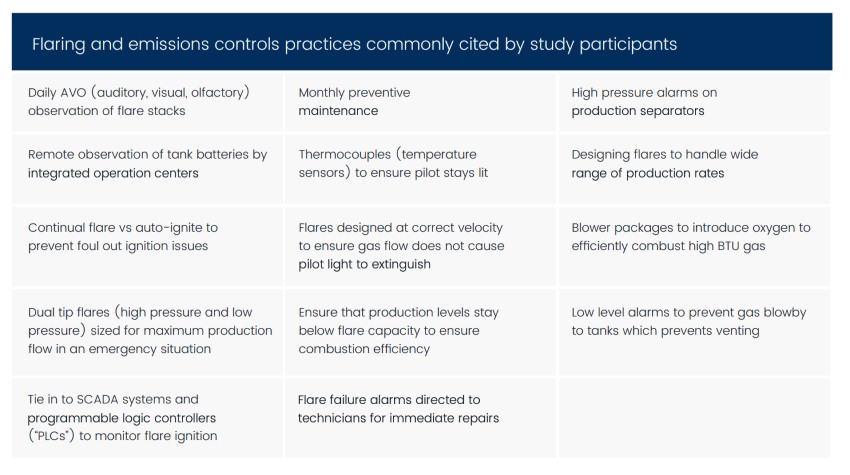

Among the best operating practices shared by participating companies is using vapor recovery units on pad sites aiming to maximize emissions capture, frequently checking flares to ensure they are functioning properly, incorporating emissions monitors on facilities design and taking a strategic approach to manage operational upsets.

Non-routine flaring is needed only when there are operational upsets, high gas line pressures or other safety reasons.

“There’s no easy fix to this issue. It’ll take a lot of work, but it is a fixable, manageable issue,” said Jeff Gustavson, vice president of Chevron North America E&P’s Midcontinent Business Unit. “Sharing best practices with all the operators is a great [and] easy step to take.”

Chevron, which has a more than 2 million-acre position in the Permian Basin, planned to produce about 600,000 boe/d this year and up to 1 MMbb/d by 2024, though Gustavson said those plans are being worked out in light of the current environment.

Industrywide curtailments are helping bring down amounts of flared gas, and the downturn is giving infrastructure time to catch up to production levels, Gustavson said. He pointed out positive economic signals from improved differential between Waha and Gulf Coast prices.

Energy research firm Rystad Energy said in April total gas flaring in the Permian dropped to an estimated 700 MMcf/d in first-quarter 2020.

Chevron aims to reduce its global flaring intensity by 25% to 30% from 2016 levels by 2023.

The environmental and economic impacts are real, Gustavson said, before focusing on the latter.

“You’re burning product which has value,” although prices went temporarily negative a few times last year, he said. Plus, he noted the market is watching, and there is heightened scrutiny on not just individual operators but the entire industry.

“Capital flows are changing because of this. That has a real economic impact,” he said.

Creating Value

When JP Morgan Asset Management analyzes energy stocks, sustainability factors are among the areas evaluated, according to David Maccarrone, a managing director with JP Morgan. The firm, he said, supports policymakers developing regulation to deliver on non-routine flaring objectives in the Permian.

“The reality is climate change needs to be high among companies’ priorities because the world is changing,” Maccarrone said. “These changes will drive company operations and stock valuations and for us. … It impacts our ability to create value for our clients.”

EDF has been tracking flaring in the Permian Basin since the start of the shale boom. Its latest research revealed that some flares have major performance problems, contributing to methane emissions in the basin.

There is an incentive problem when it comes to flaring, said Colin Leyden, director of regulatory and legislative affairs for EDF.

“You’ve got low gas prices, rush to bring production online, a lack of meaningful regulatory limits,” he said. “That’s all a recipe for excessive waste and pollution, and that’s generally what we’ve seen in the Permian. Operators are primarily there for the liquids, and the dry gas can often end up essentially being a waste product.”

He called flaring a “huge unforced error” and a “question mark hanging over the oil and gas industry’s ability to compete in a low carbon economy.”

Hopes are for companies who routinely flare to be inspired by companies that don’t, and for regulators to enact rules to make that happen.

The topic is on the June 16 agenda of the Texas Railroad Commission. Chairman Wayne Christian formed a task force to look into potential ways the RRC can reduce flaring and whether the commission should adopt a new policy on flaring.

RELATED: Coalition Gives Texas Oil Regulators Blueprint to Reducing Flaring

Texas law prohibits flaring of associated gas from initial completion beyond 10 producing days. Companies, however, may request exemptions.

Besides companies highlighted in the Gaffney Cline report, others of various sizes have taken steps to reduce flaring without stricter regulations. The problem is not every company is doing so.

“There’s an expression, ‘If you aim for nothing, you’ll hit it every time,” Maccarrone said. “The voluntary operator actions we’ve seen have not delivered on the industrywide change we need to see in time, particularly in the Permian, given its size.”

It also helps to have goals, which Stewart pointed out creates transparency to stakeholders and accountability within and outside the organization. Some companies, including Chevron, have tied compensation to flaring goals.

“It starts with that strong governance and strong leadership from the top,” she said.

Recommended Reading

Humble Midstream II, Quantum Capital Form Partnership for Infrastructure Projects

2024-01-30 - Humble Midstream II Partners and Quantum Capital Group’s partnership will promote a focus on energy transition infrastructure.

First Solar’s 14 GW of Operational Capacity to Support 30,000 Jobs by 2026

2024-02-26 - First Solar commissioned a study to analyze the economic impact of its vertically integrated solar manufacturing value chain.

SunPower Begins Search for New CEO

2024-02-27 - Former CEO Peter Faricy departed SunPower Corp. on Feb. 26, according to the company.

Green Swan Seeks US Financing for Global Decarbonization Projects

2024-02-21 - Green Swan, an investment platform seeking to provide capital to countries signed on to the Paris Agreement, is courting U.S. investors to fund decarbonization projects in countries including Iran and Venezuela, its executives told Hart Energy.

M4E Lithium Closes Funding for Brazilian Lithium Exploration

2024-03-15 - M4E’s financing package includes an equity investment, a royalty purchase and an option for a strategic offtake agreement.