Presented by:

Nabila Lazreg is outstanding in her field. She is an educated, experienced and highly skilled engineer. How does she advance in her career?

The simple answer is to network, but not all situations are that simple. Lazreg is a woman of color in an oil and gas industry dominated by white males. She is an immigrant from North Africa and non-native English speaker living in North America. And she is an engineer stationed in the oilfield, far from corporate headquarters.

“Women of color do have unique challenges in the field,” Katie Mehnert, founder and CEO of Ally Energy, told Hart Energy. “You don’t see as many, if not many at all.”

Mehnert also offered two salient points for those working in the field:

You’ve got to be there: “If women are going to get to the top of the house, they do need operations experience, absolutely, because it helps broaden a person’s resume and background, and gives them a greater chance of being competitive for the executive roles.”

You’ve got to leave: “There’s only so far you can get in the field on the ladder to the top. If you’re not in the corporate office, you may not have that ability to move up the ladder because of the access to the people, access to the information.”

‘Strong personality’

Lazreg grew up in Algeria during that country’s 1991-2002 civil war between the government and Islamist extremist rebel groups. Had they succeeded, the Islamists’ theocratic approach to governance would have harshly restricted the rights of women.

“Islamists were against women in the street and studying, but I did not quit,” she said in an email to Hart Energy. Lazreg was the only woman in her class at the École Nationale Polytechnique in Algiers to study mechanical engineering. When she graduated in 1996, she was one of only two women to complete a rigorous recruiting process and be hired by Schlumberger.

Lazreg was sent to Italy for training before returning to Algeria, a member of OPEC, to work in the field. It wasn’t an easy assignment. Women working alongside men runs counter to custom in that region and she was routinely cursed by co-workers. Even today, women only account for 20% of the Algerian workforce.

After five years, her performance earned her a relocation overseas where she landed in the Permian Basin. Eventually, her knowledge of hydraulic fracturing and shale reservoirs established her as one of Schlumberger’s subject matter experts in those areas. She has since moved on to work for an upstream producer and is based in Canada, specializing in asset development and completion operation.

The attitudes of her male colleagues in Texas and Canada do not compare to how she was treated in Algeria, but they do pose challenges. Few women choose careers that put them so close to the wellhead, nor are there many women like her in senior technical roles giving orders to men who are her subordinates.

“You had to build a strong personality to earn respect and have authority on site,” she said. “These projects are high-dollar value, very sensitive to safety and reputation. One mistake and we can kill people or lose a multi-million dollar asset, or hurt the company’s reputation. I had to be strong and assertive and firm to ensure people follow directions.”

Only one in the room

There are few women in the industry in fracking roles and Lazreg has never worked with another in her 23-year career. That may be because, of those she has encountered, most do not work at the sites and supervise shale completion operations, as she does.

And that work status often places her in the position of the only woman in the room. It hasn’t kept her from expressing her thoughts in meetings, she said, because she draws on her experience in the field and is accustomed to asserting herself with men.

But still, she is the only woman in the room. That, in itself, speaks to the workforce composition of the oil and gas industry.

“It is a big issue in in the energy sector,” Trent Aulbaugh, partner who leads the North American Industrial Practice Group at energy executive search firm Egon Zehnder, told Hart Energy. “For whatever reason, for whatever historical reason, the E&P space, particularly on the technical side, is underrepresented with minorities and it’s underrepresented with women.”

It’s not a new issue, he added, and while progress has been made, “the pace isn’t nearly as fast as I think most organizations would prefer it to be.”

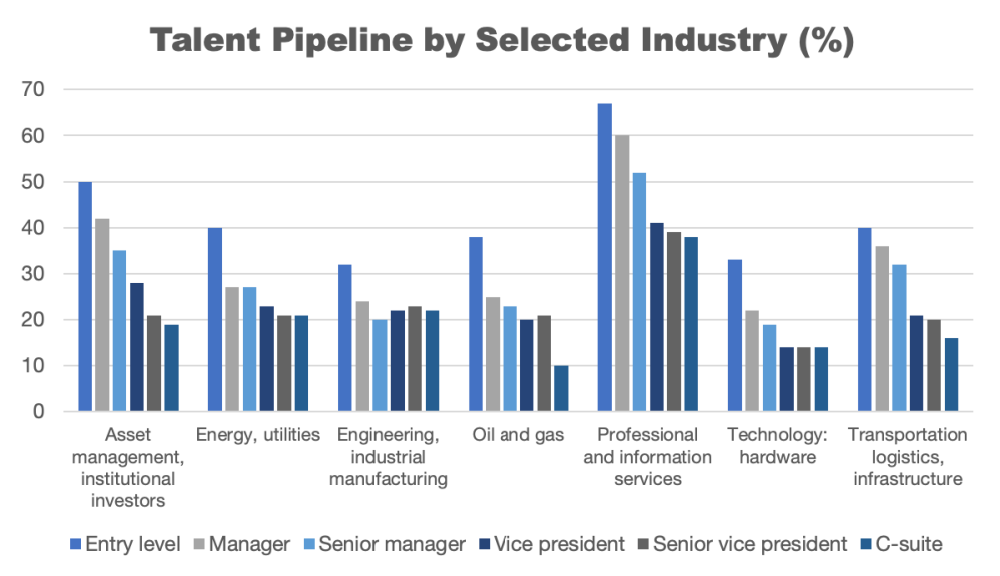

Of the 20 industries evaluated in the 2019 Women in the Workplace report by McKinsey & Co. and LeanIn.org, the talent pipeline in oil and gas was the weakest. Women constituted 38% of entry-level recruits in oil and gas. Only “technology: hardware,” “IT services and telecom,” and “industrial engineering and manufacturing” had lower percentages.

The data reflecting the ability of women to move up the corporate ladder also put the industry in a poor light:

- Second-worst at the manager level;

- Third-worst at the senior manager level;

- Dead last at the vice president level;

- In a three-way tie for fourth from the bottom at the senior vice president level; and

- Dead last in the C-suite.

(Full disclosure: Hart Energy, which annually honors the 25 Influential Women in Energy and, in 2021, published a Diversity in Energy special report, has no women and only one person of color among the 11 members of its senior leadership team.)

More opportunities

“I know that feeling of being the only,” Mehnert said. “Thank God, it’s changing since I was in the field, but there are a lot of resources out there, particularly with larger companies.”

Thanks to advances in technology and, to some extent, the arrival of COVID-19, the opportunities for career advancement are easier than ever, she said.

“If I look back at five, 10 years ago, content was limited, connectivity was limited,” Mehnert said. “Sure, we had social media and the Internet, things like that, but we were not hyperconnected like we are now. We have COVID to thank for that. We became a Zoom community overnight because we were forced to go online.”

Women took a significant hit during the pandemic, she said, because they often had to choose their families over their jobs. That’s part of the reason that people are slow to return to pre-COVID work habits. They are accustomed to the flexibility and the way of life they created during that time.

To Mehnert, that’s an opportunity for the industry to attract talent if companies are realistic about which jobs absolutely need to be filled by someone in the office five days a week. Even if warnings about a coming recession are correct, hybrid working is here to stay, she said, because it’s made people happier and more productive to have that flexibility.

Of course, that applies to office positions, not field work.

“Unfortunately, in field assignments, there’s not going to be that flexibility because of the demands of the job,” Mehnert said. During COVID, many field workers went to work. They were in plants and in harm’s way when it came to COVID because they had to be present physically at an asset.

“It makes it difficult if you’re in a field role to have the time to network because your job is operations,” Mehnert said. “When I had an operations job, I couldn’t go to a lunch meeting about women in energy. Actually, I’d get laughed at—‘you’re going to what?’”

Times have changed and companies are expected to commit to issues like diversity and inclusion, and to giving their employees the time they need to build their networks and advance their careers, she said. They are also investing in creating affinity groups to bring women and people of color together in energy.

Some of those changes have been ordered from the top, Aulbaugh said, when pressure has come from the board or executive level to tackle gender or ethnic diversity issues. While it’s important to address things at the highest levels, the mandate needs to extend throughout the company.

“Where do companies recruit? How much emphasis do they place on giving diverse candidates opportunities?” he asked. “The reality is, organizations have to think a little differently about how they hire, how they develop and how they foster an environment that is receptive to women and people of color. That’s just the reality of what’s going on, and it’s particularly pronounced in the energy sector.”

Aulbaugh cited Women in Energy and other networking organizations working to foster gender diverse executive teams and promote positive role modeling.

“There is a lot of good stuff going on,” he said. “It’s just not enough and not fast enough.”

Talent drain

But it needs to speed up, particularly when it comes to the industry’s pool of engineers. Other industries—particularly tech and financial services—have been poaching talent from oil and gas for years, luring people with competitive compensation and an attractive culture. Once they leave for Apple, Google or Meta, Mehnert said, they don’t come back. The cyclical nature of oil and gas, in which waves of employees are let go during price slumps, doesn’t help. The renewable and power sectors are also pursuing oil and gas technical employees.

Of course, this struggle to attract and retain young talent comes as older employees continue to depart, taking their experience and institutional knowledge with them.

Meanwhile, Lazreg continues her work in the Canadian oilfields. She’s good at what she does and this is where she wants to be. It’s limiting, though, which speaks to Mehnert’s point about the need to leave the field and serve in the corporate office to get ahead.

She has tried the conventional networking path but attending meetings is difficult in her current location. She has also found that most of the women attaining lofty positions in the industry tend to occupy non-technical roles in human resources, finance and law.

“From my experience, many women leaders in the USA and Canada have mastered great soft skills,” Lazreg said. “Not many women take the technical path and grow into leadership.”

Of course, that has long been the culture of the oil and gas industry for both men and women. Operations people have always left the field for the corporate office to move up in their careers. Domestic people have always sought international roles to move up in their careers.

And then there is Nabila Lazreg. Outstanding in her field. Alone. Hoping to connect.

Deon Daugherty contributed to this article.

Recommended Reading

How Diversified Already Surpassed its 2030 Emissions Goals

2024-04-12 - Through Diversified Energy’s “aggressive” voluntary leak detection and repair program, the company has already hit its 2030 emission goal and is en route to 2040 targets, the company says.

BKV CEO Chris Kalnin says ‘Forgotten’ Barnett Ripe for Refracs

2024-04-02 - The Barnett Shale is “ripe for fracs” and offers opportunities to boost natural gas production to historic levels, BKV Corp. CEO and Founder Chris Kalnin said at the DUG GAS+ Conference and Expo.