Crude oil prices will fly higher than is commonly expected, Marshall Adkins of Raymond James said at NAPE. (Source: Hart Energy; Maeer, Vector, prasit2512/Shutterstock.com)

HOUSTON—If you’re experiencing déjà vu over the current state of the energy industry, then you really need to pay closer attention—never has an outlook been this good, bad and weird.

“It is different today. There are many things in our business that no one in this room has ever seen in their career,” Marshall Adkins, managing director and head of energy at Raymond James, said during the NAPE Business Conference.

So, what does one do in an unprecedented business environment? Check the fundamentals. Then, check them again to understand why Adkins is so bullish.

“You need to know when to lean into the business activity or back away,” Adkins said. “I’m going to make the case that now is the time to lean in even though we’re at $90 crude. The backdrop, the fundamentals, I think, are massively underappreciated by the market.”

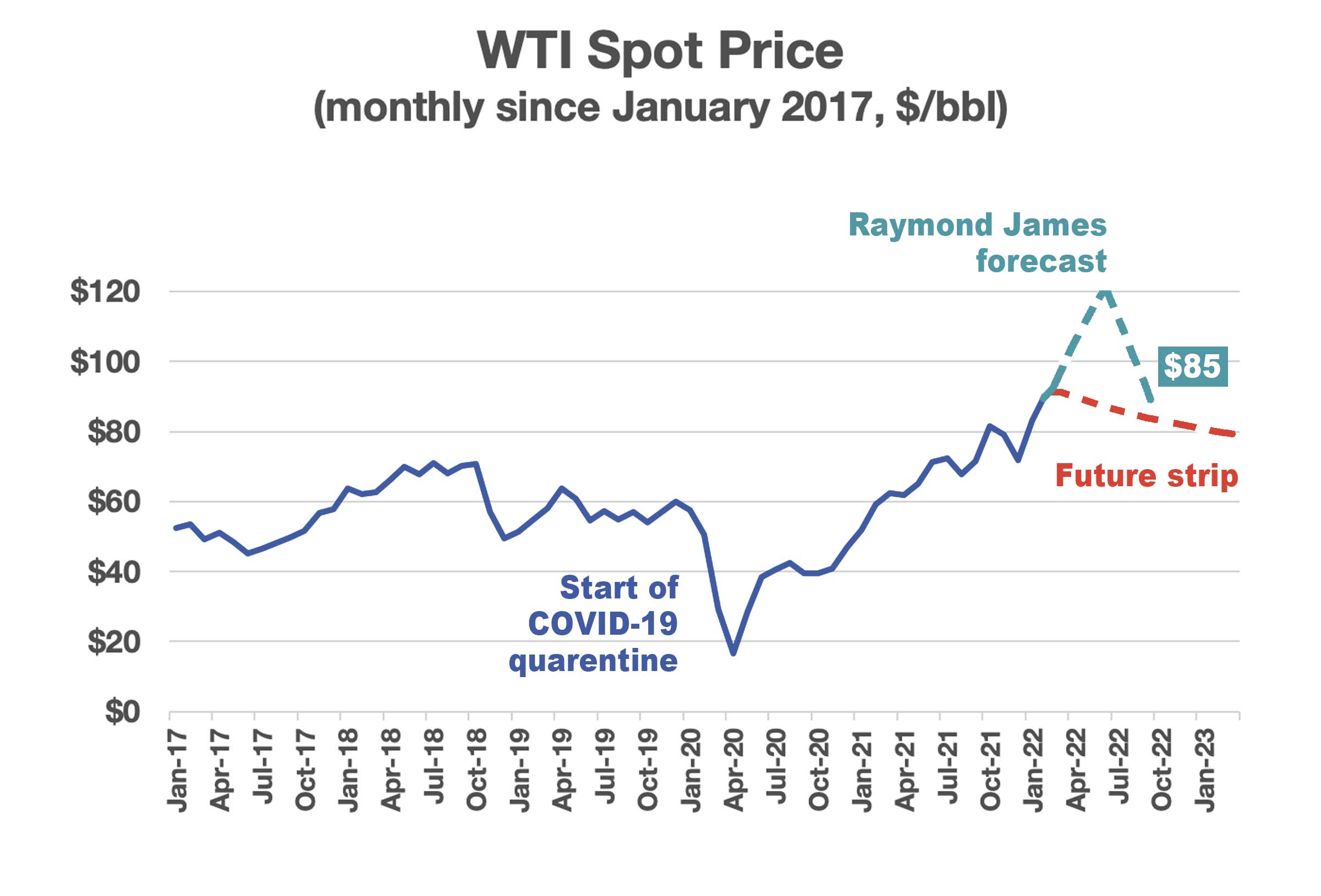

Traders, for example, don’t think the price will hold. The futures strip has WTI fading to less than $80/bbl over the next 12 months.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen next week or the week after next, but I’m pretty sure over the next couple of years, the price of oil is going to be meaningfully higher than what the futures strip is currently suggesting,” he said. “And meaningfully higher than what most of you guys are probably running in your deck for your acquisitions or projects that you’re looking at.”

Adkins pointed to these trouble areas.

Unpopularity on steroids

“We’ve never seen the level of demonization of oil and really all hydrocarbons, which has led to massive capital starvation,” he said.

It goes well beyond lawsuits and regulatory limitations that slow development and construction, Adkins said. Pressure on oil companies, particularly majors and particularly in Europe, are denying the industry necessary capital to grow production and meet demand.

“The anti-hydrocarbon stuff in Europe has literally replaced Catholicism as their religion and I think that’s forced the slowing the oil and gas of many of those majors,” he said. “And so, you’re stymying supply, pretty simple. We’ve never seen that in our careers. We haven’t seen these things come to bear.”

Hey, where did the oil go?

Supply is not responding to prices as it did in the past, he said.

“I don’t recall a period where we’ve been out of all of this stuff at the same time,” Adkins said. “Not enough coal in China, not enough coal in India, not enough natural gas in Europe and not enough oil. I mean, it’s the whole complex.”

Until this point in his career, E&Ps would spend about 125% of their cash flow, or 25% more money than they were bringing in. So, they would turn to the market, which was a terrific environment for investment bankers, who kept on raising money. Not so terrific from a return perspective, however.

“If you’re never generating enough cash to pay for that, that’s a horrible business,” he said. That’s changed. Companies now are paying back that cash flow at today’s prices. The U.S. E&P business is generating massive amounts of cash and companies are being responsible with returns.”

Also, labor issues are starting to emerge, especially in the service sector. Adkins expects those problems to continue to worsen.

That’s all they have?

“Anyone remember the last time OPEC maxed out?” he asked the audience. No one responded because OPEC never has.

“Even in the ’70s OPEC had plenty of excess capacity,” Adkins said. “They just kept it off the market. My model is showing, sometime this year, we are likely out of all excess capacity within OPEC. We’ve never been in that situation.”

The Saudis insist their capacity is 12.5 million bbl/d, but he just doesn’t see it: “They’ve never produced more than 10.8 [million bbl/d] for two months in a row.”

Russia? Flatlining production. Iraq? Nobody knows. Iran is a wild card but, even if a nuclear deal was signed tomorrow, would likely max out by 2023 if not sooner, and may not even reach 3 million bbl/d.

‘Peak’ into the future

The discussion has shifted in the last 20 years from “peak supply” to “peak demand.”

“The market is pricing oil and gas as if we are out of business in five years,” he said. “Do a discounted cash flow analysis, and go to zero in year five. That’s why you trade in two, three, four times EBITDA, because you better get your money back from the next three years, or else.”

And the price is…

Even if an agreement gets Iran pumping crude again, online excess capacity reaches zero sometime around midyear. In this scenario, Adkins envisions oil prices continuing to climb throughout 2022, assuming no meaningful interruption and inventories remaining weak, at least through the first half of the year.

“It’s a long-term price of $85,” he said, “in which I think there’s enough cash flow generated by our industry to grow production, sufficient to fuel demand growth over the next decade.”

Recommended Reading

Wayangankar: Golden Era for US Natural Gas Storage – Version 2.0

2024-04-19 - While the current resurgence in gas storage is reminiscent of the 2000s —an era that saw ~400 Bcf of storage capacity additions — the market drivers providing the tailwinds today are drastically different from that cycle.

Ozark Gas Transmission’s Pipeline Supply Access Project in Service

2024-04-18 - Black Bear Transmission’s subsidiary Ozark Gas Transmission placed its supply access project in service on April 8, providing increased gas supply reliability for Ozark shippers.

Kinder Morgan Sees Need for Another Permian NatGas Pipeline

2024-04-18 - Negative prices, tight capacity and upcoming demand are driving natural gas leaders at Kinder Morgan to think about more takeaway capacity.

Scathing Court Ruling Hits Energy Transfer’s Louisiana Legal Disputes

2024-04-17 - A recent Energy Transfer filing with FERC may signal a change in strategy, an analyst says.

Balticconnector Gas Pipeline Will be in Commercial Use Again April 22, Gasgrid Says

2024-04-17 - The Balticconnector subsea gas link between Estonia and Finland was damaged in October along with three telecoms cables.