In a separate session, Scott Tinker, director of the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University of Texas at Austin, argued that the industry helps the global poor in ways that are vastly underestimated. (Source: Offshore Technology Conference)

The view of the oil and gas industry’s global impact is decidedly mixed. At the Offshore Technology Conference, views ranged from an energy company being blamed for polluting Africa’s largest country to a geologist detailing data that, he said, shows the industry lifts people out of poverty.

In a Q&A after one conference session, Dr. Okay Harold Odocha stepped up to confront a BP executive. He said BP left some parts of his home country of Nigeria so contaminated that white clothing turns black after spending some time outside. Appearing stunned, the executive sat up a bit straighter in her chair and stumbled for an answer. As the doctor raised health concerns over pollution, a geologist, speaking in another session, detailed energy’s role in economic development which, in turn, alleviates abject poverty. The concerns and the data are part of a decades-old debate about the energy industry’s massive impact on the globe good and bad: unavoidable pollution from energy production and undeniable benefits from energy products and services.

In response to Odocha’s comments, the British energy company released a statement noting that BP “has no oil or gas production operations in Nigeria and has not done so for decades. We believe these questions may have been directed to BP in error.”

Nigeria’s government nationalized BP’s oil operations in 1979. CNN has reported the soot Odocha may have referred to comes from illegal refineries in Lagos, Nigeria.

Odocha said he paid his own way to the conference to learn more about the oil and gas industry and to challenge energy executives about environmental messes and health hazards their companies have left behind.

“We can't forget that we have huge footprints in parts of the world where there are problems with poverty, problems with bribery, corruption, poor leadership and issues with people's health and their welfare. I was concerned, and that's why I brought up the issue,” he said in an interview. He said oil and gas companies should conduct business in the developing world with the same standards they would adhere to in the U.S.

Oil and gas benefits are real, and they should be embraced, Odocha said, but the industry’s hazards should not be ignored.

In a separate session, Scott Tinker, director of the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University of Texas at Austin, argued that the industry helps the global poor in ways that are vastly underestimated.

“We are going to need the oil and gas industry in this world for a very long time. Don't be ashamed of it, be proud of it. When people ask you what you do, tell them, ‘I work in the oil and gas business, and I lift people out of poverty,’” Tinker told an audience that was nearly all from the energy industry. “Energy won’t end poverty, but we can’t get out of poverty without energy. Full stop.”

In his slides, he showed a picture of a poor African family that said he was an example of economic development helping the global poor.

“I met this man in Ethiopia. He’s about my age, and he had tears in his eyes when he told me his kids and grandkids had something he never had. They'd just come out of the bush, and they were in schools for the very first time,” said Tinker who shares his pro-energy views on his PBS talk show, Energy Switch.

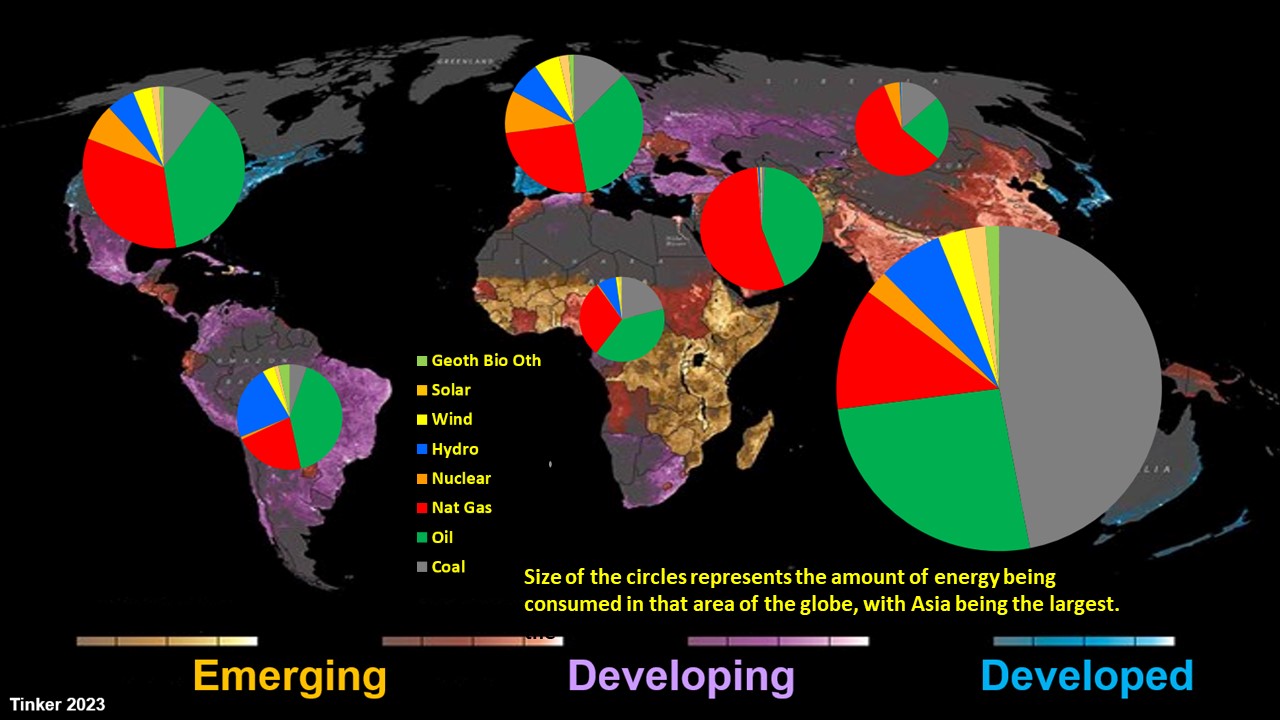

“When you think about this relationship between poverty and access to energy, it's very strong. Africa’s population is low electrified and has severe economic poverty,” he said.

Tinker said poor countries will not develop rich-world standards and capabilities to clean their air, water and ecosystems until they climb out of poverty. It takes energy to do that, and poor countries have no interest in slow-walking their economic development.

“No source of energy is going down. None. Not even hay. We consume more hay than we ever have. There’s more people, there’s more animals servicing us,” he said, pointing out that popular green solutions take tremendous resources to manufacture and end up in landfills when they wear out.

Tinker said the regulations that reduce dirtier energy production in rich areas of the world mean little because those rich areas still buy enormous amounts of products from poor areas, which burn large amounts of oil and coal to manufacture them.

Asia burns more coal than the rest of the world combined, he said, and Germany scampered back to coal when the Russian invasion of Ukraine meant Germany was cut off from Russian gas. The shift, he said, shows how countries prioritize energy security over climate concerns.

“People aren’t going to leave coal until they get reasonable, affordable options,” he said pointing out that if India burns tremendous amounts of coal to get out of poverty the way China did, it is “game over the for the climate.” Only optionality will help ease this – giving India scalable options such as natural gas and nuclear power.

In an interview after his presentation, Tinker said he agrees with Odocha’s concerns that the energy industry produces waste and pollution.

“Energy does lift the world out of poverty,” he said. “And it does need to be cleaned up.”