(Source: Hart Energy)

Learn more about Hart Energy Conferences

Get our latest conference schedules, updates and insights straight to your inbox.

[Editor’s note: Opinions expressed by the author are their own.]

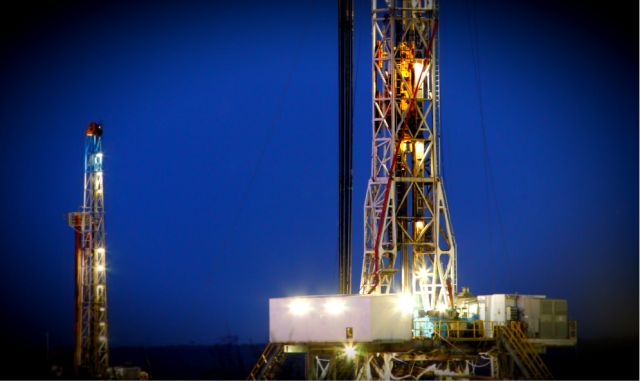

During the last two years, many observers, including me, have suggested that consolidation is needed in the upstream oil and gas industry. Logically, it’s the right response to a commodity-based business exiting a high-growth phase and facing low prices. If you can’t control prices, the thinking goes, then at least you can control costs, and of the seemingly best ways to achieve that would be to combine companies to achieve economies of scale—“synergies” in the current vernacular.

However, the expected wave of consolidations keeps not happening. The rationale for the reluctance to combine has been explained by the public market’s antipathy to the few deals that have occurred, and the difficulties combining private companies due to private equity’s cross-fund and cross-sponsor issues and their typical need to exit a business in a cash transaction to return capital to their investors.

I’ve also noticed that, despite the expectation of consolidation, new startups continue to form, which seem to contradict the thinking that the industry needs fewer rather than more companies. These observations led me to consider perhaps another reason for the lack of consolidation is employee productivity has improved more than appreciated and the potential benefits of consolidation are not as large as we think.

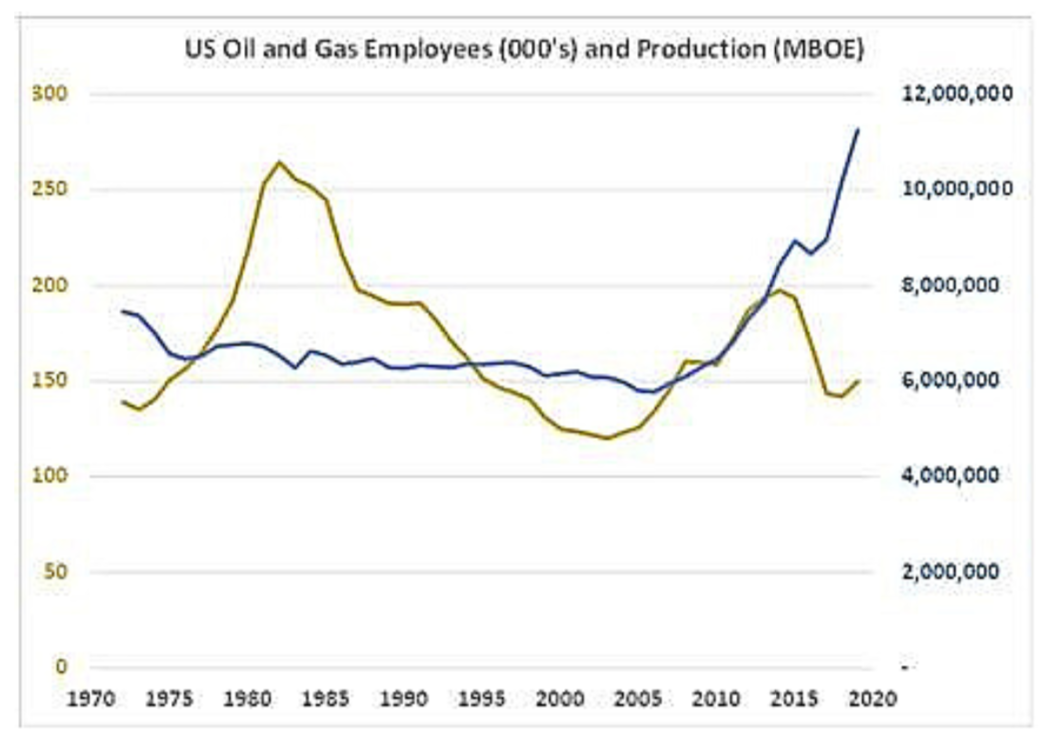

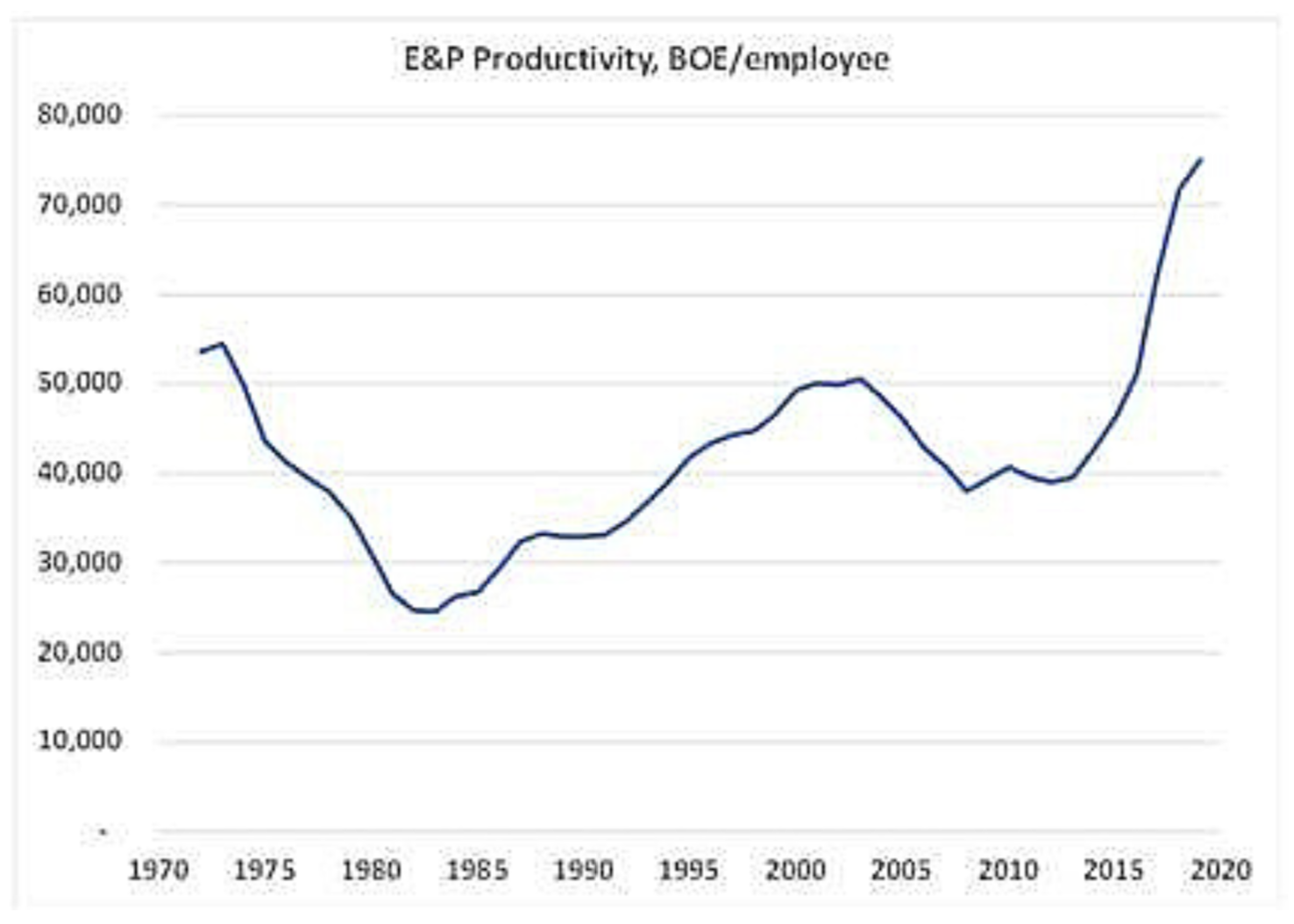

To investigate, I looked at the U.S. oil and gas production (from the EIA) compared to the number of employees in oil and gas extraction (from Federal Reserve Economic Data, or FRED) since 1972.

I began my career in 1983 and for almost all of it I’ve witnessed a significant decline in the number of people employed in the industry. During most of that time, the industry produced at a slightly declining rate and employee productivity improved. As in almost every other industry, much of this was due to the widespread adoption of desktop and other computing tools.

There was a lull in productivity growth at the beginning of the shale revolution when prices rose and employment grew, but before production growth had really taken off. Following the 2014 price drop, however, employment dropped dramatically while production continued to grow as producers improved their drilling time, completion efficiency and supply chain logistics. In 2019, productivity by this measure reached a 50-year (and probably all-time) high.

The figures shown don’t reflect the employment reduction or production declines caused by the pandemic, but don’t be surprised if productivity increases again. The industry is focusing on the best plays and big wells, along with new ways of organizing and staffing companies that may continue to drive productivity gains without corporate consolidations.

About the Author:

Steve Hendrickson is the president of Ralph E. Davis Associates, an Opportune LLP company. Hendrickson has over 30 years of professional leadership experience in the energy industry with a proven track record of adding value through acquisitions, development and operations. In addition, he possesses extensive knowledge of petroleum economics, energy finance, reserves reporting and data management, and has deep expertise in reservoir engineering, production engineering and technical evaluations. Hendrickson is a licensed professional engineer in the state of Texas and holds an M.S. in Finance from the University of Houston and a B.S. in Chemical Engineering from The University of Texas at Austin. He currently serves as a board member of the Society of Petroleum Evaluation Engineers and is a registered FINRA representative.

Recommended Reading

Endeavor Integration Brings Capital Efficiency, Durability to Diamondback

2024-02-22 - The combined Diamondback-Endeavor deal is expected to realize $3 billion in synergies and have 12 years of sub-$40/bbl breakeven inventory.

Diamondback Announces Executive Leadership Promotions

2024-02-21 - Diamondback Energy’s leadership changes follow the company’s previously announced $26 billion merger with Endeavor Energy.

E&P Earnings Season Proves Up Stronger Efficiencies, Profits

2024-04-04 - The 2024 outlook for E&Ps largely surprises to the upside with conservative budgets and steady volumes.

Viper Energy Announces Pricing of Diamondback’s Secondary Common Stock Offering

2024-03-06 - Viper Energy will not receive any of the gross proceeds from Diamondback’s secondary offering of its Class A common stock.

CEO: Coterra ‘Deeply Curious’ on M&A Amid E&P Consolidation Wave

2024-02-26 - Coterra Energy has yet to get in on the large-scale M&A wave sweeping across the Lower 48—but CEO Tom Jorden said Coterra is keeping an eye on acquisition opportunities.