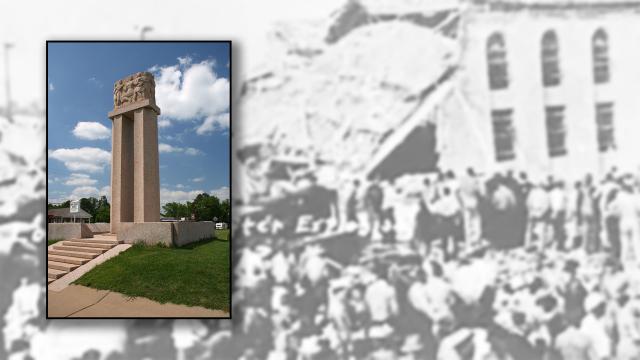

Inset: A monument in New London, Texas, honors the more than 300 students and teachers killed in the 1937 explosion that leveled the town's school. The background shows the show following the explosion. (Source: Shutterstock, The New London Museum)

Learn more about Hart Energy Conferences

Get our latest conference schedules, updates and insights straight to your inbox.

Since moving to Houston 35 years ago, I’ve developed a historical—some might call it morbid —curiosity coming from living within the virtual epicenter of three of America’s worst catastrophes.

First, there was the epic hurricane of 1900 that destroyed Galveston and left more than 6,000 dead. It remains by far the nation’s deadliest hurricane.

Second was the 1937 New London school explosion in East Texas in which over 300 students and teachers were killed, hundreds more injured, in the nation’s worst school disaster.

Third came the 1947 Texas City disaster in which ammonia nitrate, which was used as an explosive in World War II and now found useful as a fertilizer, was improperly stored aboard a French cargo ship. A lit cigarette carelessly tossed aside by a crewman found its way into the ship’s hold. The ensuing blast killed more than 580 people and left thousands injured. It is the nation’s worst industrial disaster.

Unfortunate coincidence?

These disasters were the results of a series of events all leading up to horrendous catastrophes. Was it an unfortunate coincidence that they occurred in a state that has never been known for strict regulations? That’s for history to decide. Plenty of books have been written about each possible answer.

This article focuses on the New London school explosion, which was caused by a natural gas leak and led to sweeping changes in the energy business that I wrote about on the 75th anniversary of the blast. Recently, I received a copy of Living Lessons From The New London Explosion, written in 1938 by a local pastor, Rev. R.L. Jackson, and reprinted by the New London Museum. The 92-page book offered some information that further clarified what led to the disaster and its aftermath.

The New London school was in the center of the fabled East Texas oilfield. The community was prosperous enough to spend $1 million ($18.5 million nowadays) on the construction of the state-of-the-art building in 1932 and its expansion in 1934, with 737 students enrolled. It was the first school in the state to have electric lights on its football field. But one problem existed: constructing the school on sloping ground with a large enclosed air space beneath the building that stretched along the entire 253-foot façade.

The school board overrode the original architectural plan for a boiler and steam distribution system. Instead, they decided to install 72 gas heaters throughout the building. Then, they decided they could save on the $250 a month they were paying to the local gas company by rigging a device to a pipeline that was carrying Parade Gasoline Co. residual gas that would otherwise be burned off.

Illegal taps

It was a common ploy for homeowners and businesses to illegally tap into pipes carrying waste gas, with no thought given to the volatility and instability of the odorless, colorless gas. Refiners were later blamed for failing to enforce policies barring gas line taps.

The New London school’s gas pipes were often jostled by students and teachers. The sub-basement was also very poorly vented. At the time of the explosion, Walter Cronkite was a 20-year-old cub reporter for a wire service and drove in from Houston on his first major assignment. He reported that the architect had reinforced the building with vertical rows of tiles. Gas was leaking from the residual line tap and had built up within the 15,000-quare-foot sub-basement, soon filling the vertical columns of tiles.

“The school was a bomb waiting to explode, two minutes before school was to be dismissed for the weekend,” Cronkite wrote. One report later said that students had been complaining of headaches but received little attention.

Jackson wrote that the explosion occurred when a teacher in the woodshop located adjacent to the sub-basement plugged an electric sander into a portable connection. A door to the gas-filled sub-basement was partially open, some of it seeping into the shop, and was ignited by an arc formed when the two prongs of the portable switch touched the socket before it was driven into place.

The walls bulged and the roof lifted from the building as the main wing of the school collapsed. The death toll might have been even worse had it not been for roughnecks from the nearby oil fields who rushed to the scene with cutting tools, special lights and heavy equipment needed to dig through the wreckage.

Mercaptan

In the aftermath, the Texas Legislature passed the first law requiring the addition of a malodorant, Mercaptan, to natural gas to give early warning of a leak. Another new law required that anyone working with gas connections be trained and certified as an engineer by the state.

Heath Consultants Inc. has been a world leader in gas leak detection since the Houston-based company was founded in 1933. Paul D. Wehnert is senior vice president for sales and marketing. He’s been with Heath for over 30 years and graduated from the State University of New York at Syracuse with a degree in environmental science. He is a frequent speaker on gas leak detection so I asked him how that business has evolved since New London.

Wehnert said the majority of gas leaks occur in this manner:

- Cast iron—bell joints/graphitization;

- Bare steel—corrosion;

- Plastic—poor fusion joints/electrofusion fittings;

- Cathodic-protected steel—welds, coating flaws;

- Clamps, fittings, dresser couplings, etc.;

- All pipe experiencing third-party damage; and

- Environmental acts—hurricanes, earthquakes, flooding, etc.

He said that, prior to 1937, gas leak detection generally relied on visual vegetation surveys looking for dead vegetation caused by venting leaks from both natural gas and manufactured gas (coal gasification). Federal regulations were minimal until Congress passed the Natural Gas Pipeline Safety Act of 1968. Leak detection is a requirement under the DOT Federal 192 regulations based on pipe location and material. All natural gas companies must respond to public/customers leak and odor calls with appropriate leak detection technologies.

“The immediate impact of New London was not allowing the public to take natural gas from producers directly for consumption without being adequately odorized. All odorant is added to natural gas for the public so in the event of a leak they have early warning. The gas in New London was supplied direct from the wellhead and not odorized. Thus, when the leak developed, the public didn’t know,” Wehnert said.

Detection techniques

Flame-ionization detectors became one of the early tools used to find gas leaks. They have since been replaced by optical infrared and laser-based technologies, he said.

So, with natural gas becoming more prevalent, is the job of detecting leaks getting more difficult?

“Local distribution companies are highly regulated with respect to mandated leak detection,” Wehnert answered. “Transmission companies are required to do mandated inspections on Class 3 and Class 4 locations. Wellhead—gathering—gas processing are not as regulated, and this is where more requirements will be forthcoming, both DOT-regulated and environmental, EPA.”

Some of the new innovations being used to help detect leaks include fixed deployment of methane sensors in high-consequence areas, aerial surveys using fixed wing aircraft, helicopters and drones. More sensitive Advanced Mobile Technology devices are also being mounted in vehicles, he said.

What’s Heath’s strategy in maintaining its edge as an industry leader?

“We continue to listen to our customers and follow regulatory requirements to keep ahead of the technology curve. We are seeing an even higher impact of natural gas leaks for not only public safety, but also as a greenhouse gas emission with respect to environmental issues. Obviously, we have regulations from the federal government with DOT/PHMSA, but now requirements from the federal EPA as well,” Wehnert said.

During the recovery, workers salvaged a blackboard with this written on it: “Oil and natural gas are East Texas’ greatest mineral blessing. Without them this school would not be here and none of us would be here learning our lessons.”

Perhaps one lesson to be learned is what the earth gives us, it can also take. Perhaps we should remember that as we learn more about the cause and effects of climate change. Perhaps we also need to remember not to skimp on our schools when officials look to cut costs.

“I did nothing in my studies or in my life to prepare for a story of the magnitude of the New London tragedy, nor has any story since that awful day equaled it,” Cronkite wrote in his autobiography.

As for me, I’m glad I hadn’t been born yet.

Jeffrey Share is a Houston-based Hart Energy contributing editor specializing in midstream energy topics.

Recommended Reading

Private Equity: Seeking ‘Scottie Pippen’ Plays, If Not Another Michael Jordan

2024-01-25 - The Permian’s Tier 1 acreage opportunities for startup E&Ps are dwindling. Investors are beginning to look elsewhere.

Some Payne, But Mostly Gain for H&P in Q4 2023

2024-01-31 - Helmerich & Payne’s revenue grew internationally and in North America but declined in the Gulf of Mexico compared to the previous quarter.

Uinta Basin: 50% More Oil for Twice the Proppant

2024-03-06 - The higher-intensity completions are costing an average of 35% fewer dollars spent per barrel of oil equivalent of output, Crescent Energy told investors and analysts on March 5.

In Shooting for the Stars, Kosmos’ Production Soars

2024-02-28 - Kosmos Energy’s fourth quarter continued the operational success seen in its third quarter earnings 2023 report.

M4E Lithium Closes Funding for Brazilian Lithium Exploration

2024-03-15 - M4E’s financing package includes an equity investment, a royalty purchase and an option for a strategic offtake agreement.