(Source: Alexandr Nagornyh / Shutterstock.com)

Business school theories can seem basic, but there are some frameworks and buzzwords that can be a useful lens to view the current midstream landscape – more useful because so much has changed in the sector in a short period of time.

Industry life cycle

The first concept is the industry life cycle, which includes five stages: startup, growth, shakeout, maturity and decline. The growth phase for midstream was roughly the decade that ended in 2014, with high capex to build infrastructure in support of high production growth from unconventional development of shale basins. The sector then had an unusually long shakeout period that ended at some point in the past few years, typified by new entrants competing margin away, leading to fewer viable companies.

That brings us to the current stage: maturity. In this stage, growth is limited, so there’s less need for capex. The focus shifts to reducing expenses, which leads to further consolidation that tends to be accretive to margins as scale can reduce per unit costs and overhead can be spread over a larger business. Industries in this phase seek to deter entry of new competitors to maintain profitability.

This stage generally has the highest cash flow. The maturity stage can last a long time, but the stage that follows is the decline stage, when companies become increasingly desperate to survive even as the industry starts to fade.

But for now, midstream is mature, and investors are pushing companies within this industry to focus on slowing investment, growing free cash flow and returning capital. Investors want them to be cash cows—another great business school buzzword.

Porter’s Five Forces

The next business school concept to explore is “Porter’s Five Forces,” which seeks to identify where an industry’s strengths and weaknesses are that can help with competitive advantages.

Competition within the industry is one of the Five Forces. In midstream’s growth phase, with abundant capital available, there was intense competition. After years of consolidation, inflation of materials and labor, higher interest rates and low returns for private capital, competition within the industry has been reduced substantially.

“Threat of new entrants” is another of the Five Forces that has shifted in favor of existing midstream operators. In addition (or perhaps as a result), the power of customers (another of the Five Forces) has been reduced. A decade ago, when a fragmented midstream industry served few large companies, the power of major customers like Exxon Mobil Corp. or Pioneer Natural Resources Co. was extremely high and that led to the overbuilding of pipelines and processing capacity in certain regions with high production growth. However, not so today, especially with regulations creating larger hurdles to new energy infrastructure.

The improved competitive positioning of midstream companies within the broader energy value chain could potentially lead to higher rates and higher margins for remaining midstream operators. It may finally come to pass that existing pipe in the ground sees its value realized in the form of pricing power and growing margins, even if volumes stagnate. The biggest threat to this improved competitive position is customers reverting to building their own infrastructure.

No new entrants

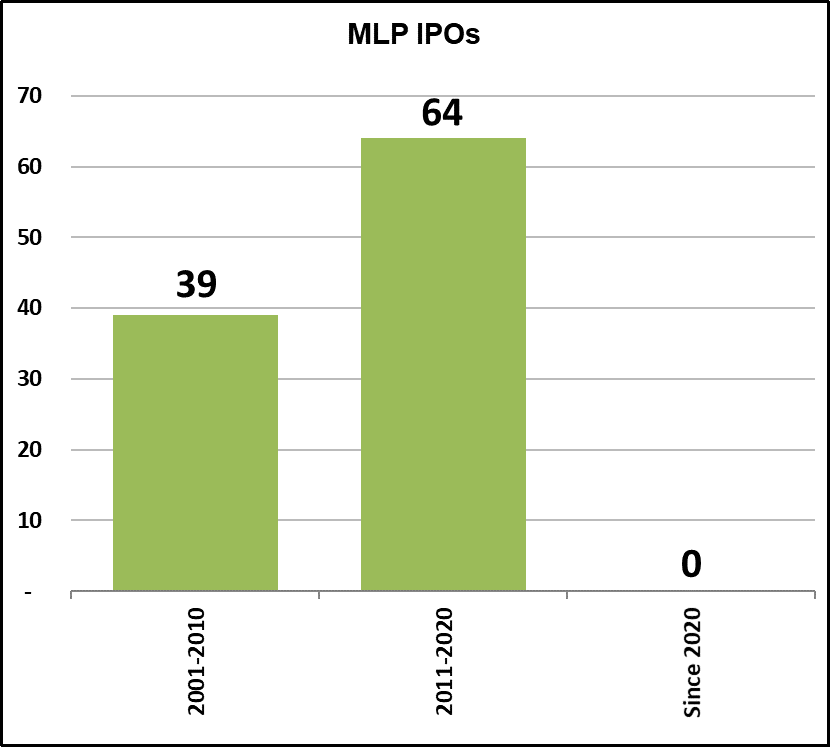

New company formation in midstream is at its lowest point in the sector’s history. Rattler Midstream’s IPO in 2019 was the last real IPO in the space. Since then, Kinetik Holdings was created via a special purpose acquisition company that combined with Blackstone’s midstream business, and DT Midstream was spun out of utility company DTE. Even counting those, we are talking about just three new companies in four years.

Compare that to 75 IPOs in the 10 years from 2006 to 2015, a more than seven per year average, not counting the general partner holding company IPOs (another 14 tickers) and not counting the coal, nitrogen and E&P MLPs (another 30 or so tickers).

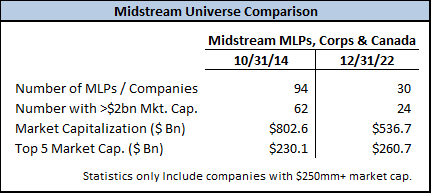

Back in October 2014, just before the roll up of Kinder Morgan’s MLPs closed (eliminating KMP, KMR and EPB), there were 94 publicly traded companies in the midstream space, including MLPs, U.S. corporations and Canadian corporations. 62 of those companies had market capitalizations greater than $2 billion.

Today, there are 30 remaining companies and 24 with market capitalizations greater than $2 billion. There is a recent high for midstream companies in the S&P 500 at four, though.

Old companies are going away, new companies are not being formed and competition among the industry is lower than at any point in the past 20 years. The major shakeout period for the industry is behind us, setting up a period of maturity and free cash flow that should endure as the world slowly transitions to a more inclusive energy mix with renewables displacing oil and coal over time.

There is a path for midstream to become more infrastructure-like to fulfill that old promise of pipeline assets as being toll road-like. Comparing pipelines to toll roads became a punch line in the past decade because previously stable cash flows and dividends proved to be far more volatile than promised.

Volatility in commodity prices, higher-than-reasonable leverage, higher-than-reasonable payout ratios and easy access to capital were the culprits. While commodity prices were not controllable, many of the challenges of the sector were self-imposed and therefore can be better managed to make midstream more toll road-like than ever.

Hinds Howard is a portfolio manager at CBRE Investment Management where he evaluates listed energy infrastructure and transportation companies in North America and coordinates research of listed transportation companies globally. He is based in Wayne, Pa.

Recommended Reading

High Interest Rates a Headwind for the Energy Transition

2024-04-18 - Persistent high interest rates will make transitioning to a net zero global economy much harder and more costly, according to Wood Mackenzie Head of Economics Peter Martin.

Exclusive: Mitsubishi Power Plans Hydrogen for the Long Haul

2024-04-17 - Mitsubishi Power is looking at a "realistic timeline" as the company scales projects centered around the "versatile molecule," Kai Guo, the vice president of hydrogen infrastructure development for Mitsubishi Power, told Hart Energy's Jordan Blum at CERAWeek by S&P Global.

Google Exec: More Collaboration Needed for Clean Power

2024-04-17 - Tech giant Google has partnered with its peers and several renewable energy companies, including startups, to ramp up the presence of renewables on the grid.

US Geothermal Sector Gears Up for Commercial Liftoff

2024-04-17 - Experts from the U.S. Department of Energy discuss geothermal energy’s potential following the release of the liftoff report.