The Duvernay Shale caught the attention of the oil industry in 2012 when EOG Resources Inc. drilled a well into the oil window of the East Shale Basin, but the company chose to walk away from that well.

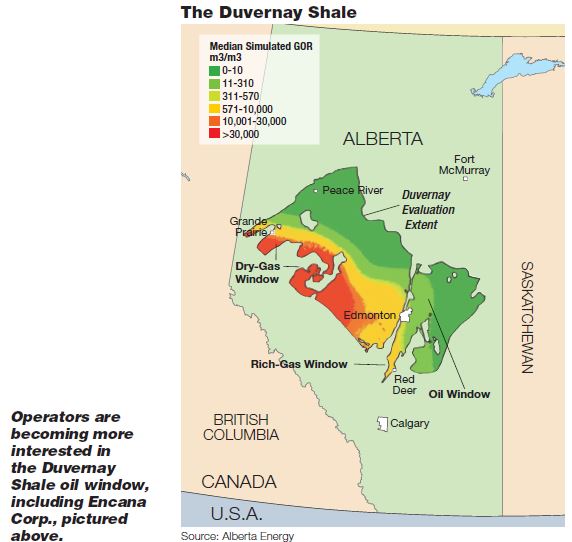

Since then more E&P companies have decided to drill in the play, which unfolds between Calgary and Edmonton in central Alberta, more recently moving from the gas window to the light oil window. In addition, activity in the Duvernay has shifted from exploration into the early stages of commercial development.

“Recent analyst reports are pointing to IP30 rates of 300-plus boe/d [barrels of oil equivalent per day] and EURs exceeding 300,000 boe (90% oil) for a US$45 WTI breakeven cost. As the shales are thinner, thermally less mature and have higher carbonate content, the East Shale Basin Duvernay is a different animal than its western neighbor,” said a report by Calgary research firm Canadian Discovery Ltd., last year.

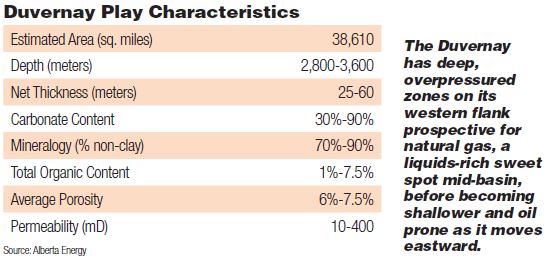

The play is estimated to contain 820 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of natural gas along with more than 300 billion barrels of oil and NGL. The original oil in place was estimated at 725,000 boe per meter per section. The dry gas, liquids-rich gas and oil windows cover some 38,610 square miles, according to Alberta Energy. The net thickness ranges from 82 to 165 feet. Total organic content is 1% to 7.5% with an average porosity of 3% to 7.5%.

“With a 6% recovery factor and a 1-mile lateral, companies could recover about 250,000 bbl. What’s happening now is that people are drilling 2-mile laterals so the recovery they are getting is higher,” said Kaush Rakhit, CEO of Canadian Discovery.

“In the last few years some of the former EOG team members joined Vesta Energy Corp., picking up where EOG left off. Vesta and Artis Exploration Ltd. are the two major drillers on the play right now. They are both private companies,” he added.

Oil window attracts more players

“The original focus for exploration was the southwest corner of the Duvernay in the Willesden Green area, with deep natural gas being the initial target,” according to “Managing the Curve,” a recent report issued by Calgary research and data firm CanOils, the Daily Oil Bulletin and Baker Hughes GE.

“The vast majority of Duvernay wells have been drilled at Kaybob, but 2017 saw increased activity in the East Duvernay Shale Basin, targeting oil in shallower zones,” the report explained.

Several companies, including majors like Shell and Chevron, are moving into full-scale commercial development in the Kaybob area. Production from the play is expected to start rising throughout 2018 to 2019 and later, the report added.

However, the greatest activity is being conducted by juniors and mid-size companies funded by private equity, noted Rakhit.

Raging River Exploration Inc. is an example of a large junior/mid-size company. It was merging with Baytex Energy Corp., with a closing expected in August. Baytex, the pro forma surviving company, will end up with 750 horizontal locations in the emerging East Duvernay light oil play. It estimates that if WTI oil is $65/bbl, then internal rates of return will be 80% for the East Duvernay.

In first-quarter 2018, Raging River had production of 24,118 boe/d with 88% oil. The company said it had 262,400 net acres in the East Duvernay.

“This combination creates a diversified, well-capitalized oil producer that has an impressive suite of high-quality producing assets and the ability to materially advance our East Duvernay Shale light-oil opportunity,” said Neil Roszell, executive chairman and CEO of Raging River, in a June 18 press release when announcing the deal.

Crescent Point Energy Corp. recently entered the light-oil play at a low cost of about $315 per acre, and now has more than 355,000 acres in the East Shale Basin. During its recent quarterly report, it said it was monitoring early, “encouraging” Duvernay well results before making further capital decisions. (Editor’s note: Working under an interim CEO, the company is undergoing a strategic review.)

The company expects the play to provide scalable economic growth with high-impact production and strong returns. The organic expansion is expected to be funded through the sale of noncore assets, according to the company’s first-quarter 2018 report, issued May 3.

Crescent Point participated in two gross (one net), nonoperated horizontal wells with a lateral length of 1.5 miles in the East Shale Basin. The first well flowed at a 30-day IP rate of 570 boe/d (92% oil and liquids). The 30-day IP on the second well was 535 boe/d. The company’s capex budget included four net operated wells in the first half of 2018, according to the release.

Privately held Vesta Energy is a larger company that operates in what it calls the Joffre Duvernay Shale Oil Basin. The company has amassed 275,000 acres in this shale and drilled 70 wells. It currently produces over 7,000 bbl/d of 42-degree API oil, and has an inventory of more than 2,000 drilling locations.

In 2018, the company won the Explorers and Producers Association of Canada’s EPAC Award for top emerging private producer. The company was initially funded by JOG Capital. In May 2017, the company entered into an agreement for a C$295 million equity financing co-led by Riverstone Holdings LLC and JOG Capital.

Seeing the play was similar to the Eagle Ford Shale, Vesta first partnered with EOG and then later bought EOG’s position.

Understanding the East Shale Basin

In the oil window of the East Shale Basin, the shale is shallower at 7,260 to 8,250 feet deep.

“Since 2016, over $400 million has been spent on land,” Rakhit said. “Most of the land is gone.

A lot more wells are being drilled. People are just starting to get wells that have IP rates on the order of 500 bbl/d. Estimated ultimate recoveries [EURs] are maybe 300,000 bbl of oil, with some of the better wells reaching 450,000 bbl.

“I would say the play is still in the early stages. The early players got into some of the core in the thickest parts of the play,” he continued. “Now there are new entrants, and there is a lot of appraisal drilling that is starting.”

The East Shale Basin tends to be more carbonate rich than the west. “People are just trying to figure out where the storage is and where the sweet spots are. There is a lot of geologic variability that needs to be understood to commercially unlock the play. There definitely are sweet spots, and there are spots that are more technically challenging. I think there is still a lot to learn,” he emphasized.

Rakhit warned that operators need to know where they are in the play. “Understanding thermal maturity is one of the keys as the ‘oil’ play gets pushed both updip and downdip. If you get close to reef complexes you can get porous streaks coming off the reef and potentially have water or poor hydrocarbon charges. Thicknesses change and are not uniform everywhere so the amount of original oil in place changes. You need real science before you drill because it is a lot cheaper. Those learning wells can be expensive.”

Canadian Discovery does three primary things—upstream information services, oil and gas data, and consulting on geoscience and strategic services. The company released a multi-client study in June 2018 titled, “South Duvernay Oil Play Phase II: East Meets West.” It has been gathering data on the play since 2011. Companies can use that kind of information to narrow the focus of their development.

Lowering capital costs

CanOils noted that 147 wells were drilled in the Duvernay in 2014, a 58% increase from 2013. Then the commodity price collapsed, and the number of wells drilled has been relatively flat. Oil production has climbed by 320% from the first quarter of 2013 to the fourth quarter of 2017.

This upward trend is expected to continue as more East Shale Basin wells are drilled.

One of the drivers for the increased activity is lower capital costs. There are a number of advantages that make the play attractive.

“One of the big advantages in the East Shale Basin area is year-round accessibility. There are roads and infrastructure. It is a lot cheaper than trying to go into the deep woods,” Canadian Discovery’s Rakhit said.

Since the shale is shallower here, drilling costs are cheaper. The typical wells are in the C$6-to C$8-million range, with the higher range for 2-mile long laterals. Companies are probably doing 50- to 60-stage completions on those, using slickwater completions, he explained.

“The technology has evolved. People who are breaking into this play have pre-existing advancement in knowledge about the work that has been done in other parts of the Duvernay, the Eagle Ford and the Permian—all of these tight-oil plays. I think that provides a big advantage.

“You still have to test what works, obviously, but you’re not starting from scratch,” he continued.

The report from CanOils, the Daily Oil Bulletin and Baker Hughes GE listed seven reasons why capital costs have gone down, with technology one of the main factors. High-performance AC drilling rigs with automated pipe handling, walking systems and large pipe-racking capacity are dominant in the Duvernay. Also, because of the downturn, the best rig crews are available, helping to improve drilling efficiency and effectiveness.

As mentioned previously, lateral lengths have been increasing steadily since 2014, which helps lower costs per boe of production.

The third reason noted in the report is faster drilling speeds. Rigs have more than tripled meters drilled per day since 2014. The move from exploratory drilling to pad development likely contributes to the increase.

From 2014 to 2017, the cost per meter drilled dropped by 38% to about $500 per meter from $1,300 per meter. Again rig efficiency and lower day rates because of the price decline were major factors, the report said.

The fifth factor is the higher number of stages because of the longer laterals. The majority of Duvernay wells in 2015 were completed with 25 to 35 stages. In late 2016, the number of stages increased to a range of 45 to 95 stages.

Longer laterals and larger completions paid off in higher EURs in the Kaybob Duvernay, which have increase by 63% as the play moved from exploration to development.

Finally, the report noted, the capital cost per boe of EUR dropped significantly by 46% to $10.89/boe in 2017. While cutting capital costs per boe recovered is a major step in commercialization of the Kaybob Duvernay and the East Shale Basin oil plays, keeping the wells producing as long as possible will determine ultimate profitability.

Other aspects that impact capital costs include using plug-and-perf technology, tighter spacing to increase fracture treatments, increasing proppant loads and cutting completion costs by more than 50% in the last three years due to design evolution and multipad wells.

Average payouts for wells at $55/bbl are 26 months for the Kaybob and 17 months for the East Shale Basin, the report said. Artificial lift is a key to oil profitability. Installation cost is around $250,000 for electrical submersible pumps, and replacements cost about $150,000. Pump-and-rod systems then are used when production declines, although some operators go straight to these systems.

Recommended Reading

Oceaneering Won $200MM in Manufactured Products Contracts in Q4 2023

2024-02-05 - The revenues from Oceaneering International’s manufactured products contracts range in value from less than $10 million to greater than $100 million.

CNOOC’s Suizhong 36-1/Luda 5-2 Starts Production Offshore China

2024-02-05 - CNOOC plans 118 development wells in the shallow water project in the Bohai Sea — the largest secondary development and adjustment project offshore China.

TotalEnergies Starts Production at Akpo West Offshore Nigeria

2024-02-07 - Subsea tieback expected to add 14,000 bbl/d of condensate by mid-year, and up to 4 MMcm/d of gas by 2028.

Sangomar FPSO Arrives Offshore Senegal

2024-02-13 - Woodside’s Sangomar Field on track to start production in mid-2024.

CNOOC Makes 100 MMton Oilfield Discovery in Bohai Sea

2024-03-18 - CNOOC said the Qinhuangdao 27-3 oilfield has been tested to produce approximately 742 bbl/d of oil from a single well.