(Illustration by Robert D. Avila)

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the October 2020 issue of Oil and Gas Investor magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

Choosing performance metrics and setting incentive award opportunity targets in executive compensation programs is hard in any industry. It’s even harder in highly cyclical industries, with oil and gas posing a particular challenge due to the frequent cycles that are extreme at both the lower and higher ends. Companies and their boards must balance a variety of issues such as motivating performance (even if the company may enter bankruptcy or a restructuring in a downturn); retaining critical leadership talent (especially if on the upswing, executives become recruiting targets); and ensuring stockholder support, which can be tricky at any time.

Decisions and communication about metrics and compensation levels have always sent important signals to current and potential investors about where a company is focused, its strength of position within its own industry and how it intends to create stockholder value over the long term. And we know there is no shortage of armchair quarterbacks in executive compensation—regulators, institutional advisory firms, the media, activists and so on.

Of course, the critics are less vocal when times are good—a rising stock price solves a lot of problems. When an industry sector outperforms the market, most agree that companies with performance results at the top of their industry should pay their executives above target awards. On the other hand, criticism of management is often intense in a difficult market, and at the same time, the need to retain an effective leadership team is more important than ever.

So, is it also reasonable for a company to pay its executives target or above target award levels when it outperforms its industry peers but the entire industry sector is underperforming the broader overall market?

With the world turned upside down, the answer is not straightforward. The traditional lens through which “pay for performance” has historically been viewed is cracked. What happens now for boards that must make 2020 performance assessments without the benefit of relevant benchmarks or experience with such a tumultuous year?

Flaws in relative performance metrics

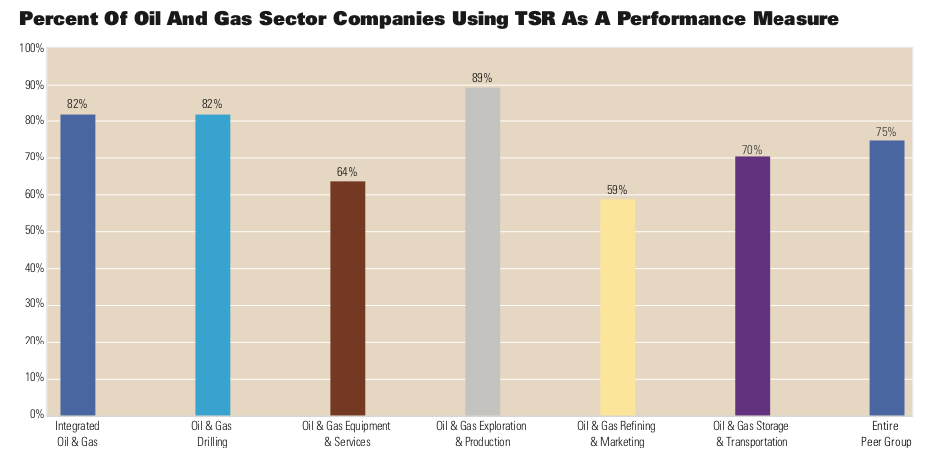

Let’s start with an examination of peer comparisons and how that may have complicated the current scenario. Over the last decade, the use of relative performance metrics, such as relative total shareholder return (rTSR), as a dominant performance metric in long-term incentive plans has exponentially increased, and it has become one of the most prevalent metrics in the oil and gas sector. Approximately 75% of companies use rTSR in their incentive plans.

The use of rTSR specifically has grown in part as a result of proxy advisors looking at three-year rTSR to evaluate pay for performance, which is happening despite Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) clearly stating they do not endorse rTSR, or any specific plan design, for that matter.

The concern is that as certain industries struggle more than others, the prevalence of relative performance metrics such as rTSR in executive pay packages may be leading to a pay-for-performance disconnect. In particular, plan designs heavily weighted toward relative measures may be driving above target payouts even when the industry comparator or peer group underperforms the overall market and the stockholders have taken it on the chin.

But compensation isn’t a theoretical discussion. It’s easy to rush to judgment and think we see pay-for-performance disconnects—especially when looking from a distance only at low sector performance. The reality is true pay for performance is not just about results tied to financial metrics.

Boards see the actions executives take in real time to navigate complex situations. They see decisions made that are intended to put their company in stronger future positions, such as acquisitions, expansions or investments. They see leadership behaviors that drive engagement and productivity throughout the workforce. Of course, boards also know full well that companies must produce results, so if the executive team isn’t driving performance in some fashion, they usually don’t stay employed very long.

However, if the executive team is doing the right thing, how does a company keep them through the toughest times while still being true to a pay-for-performance philosophy?

The answer is balancing metrics and improving communication. As the economic landscape is rattled by seismic changes brought on by COVID-19 and the price of and demand for oil remains low, we have an opportunity to reexamine specific areas of executive compensation design to help ensure that these programs include guardrails that protect against unintended consequences while aligning the best interests of stockholders with those of senior executives.

We must also increase the dialogue between companies and investors—meeting disclosure requirements alone is not enough. In a struggling industry, ongoing and active discussions are perhaps the most important guardrails in ensuring stakeholders understand a company’s intentions.

Relying on more absolute metrics

Ten years ago, relative performance metrics were rare. Most incentive plans, whether annual or long-term, were built primarily on absolute metrics, that is a target—usually financial but also possibly strategic—set by the board that is based on company performance. Under these types of plans, incentive award targets were straightforward and set based on business plans and forecasts.

The challenge with absolute metrics is that many times what can be reasonably achieved simply isn’t very good compared to historical performance or other industries. For example, when the price of oil is $30, it’s not realistic to expect the same level of financial performance as when the price of oil is $60. There is nothing wrong with setting a performance target based on forecasts and what reasonably can be achieved. Executives don’t control the price of oil and gas, and their ability to deliver financial performance is limited to the environment in which they operate.

Yet, boards and executives alike know there needs to be accountability for achieving performance targets and creating stockholder value. While setting performance targets based on expectations is reasonable, pay that’s divorced from the stockholder experience is not.

As such, investors must understand the rationale behind the goal-setting process, as well as understand what the performance expectations are and why target performance goals are considered to be appropriately robust. These concepts are complex and should be addressed in ongoing discussions and clearly summarized in disclosures. This scenario is where communication is critical.

Enduring standards—the holy grail?

Some companies consider setting performance targets based on “enduring standards,” a metric that transcends the performance cycle and works independent of forecasts. Exceeding the cost of capital is an example of an enduring standard. If you create value when your earnings exceed the cost of capital, then it makes sense that incentives should be paid. When cash flow is less than the cost of capital, value is destroyed, and incentives should not be paid. It would appear to be the holy grail of compensation measures.

But something went awry when setting enduring standards in the oil and gas industry: Commodity prices got in the way.

Even with an enduring standard, when you mix in the volatility of oil and gas prices, things can go sideways quickly. It may not be reasonable to pay at maximum when prices spike if the organization underperforms its peers. Likewise, if targets set in a downcycle are taking into account a low pricing environment, it may not be reasonable to pay target in the downcycle and maximum in an up cycle.

Adjustments in comparative metrics

Despite the drawbacks, incentive plans that use relative performance metrics (including rTSR) can still be effective as long as they have a few guardrails built in. Here are a few things you can do to fix the flaws.

Revisit the comparator group. How is the comparator group selected? Is it composed only of a company’s direct peers, or does it include some companies in general industry? Expanding the comparator group to include companies that compete for investors suggests that a company pays for relative sector performance but also pays for relative market performance.

A better comparator group could include a mix of same sector and general industry companies, or there could be two separate comparator groups (one group could be the sector group, the other could be a mix of general industry companies or an index; for example, capital intensive industrial companies in the S&P 500).

Of course, if the sector is underperforming, we must keep in mind that the company’s stock price will be lower relative to other industries, which in a way is self-regulating. While award payouts (assuming they are stock-based) may be above target for above sector performance, for an underperforming sector the lower stock prices will result in lower realized compensation.

*Oil and gas sector companies with over $500M of revenues traded on a US or Canadian exchange. Approximately 75% of oil and gas companies use TSR as their performance measure.

Balance relative metrics, such as rTSR, with other measures. If only 25% of the total long-term incentive grant is based on rTSR, it’s unlikely that compensation will be unreasonable. Balanced with other measures, a relative metric can complement the others.

For example, mixing an absolute metric based on a forecast with a relative metric can provide balance. Targets based on a forecast provide an incentive tied to a reasonable estimate of what you think you can achieve. Matching it up with a relative metric provides context.

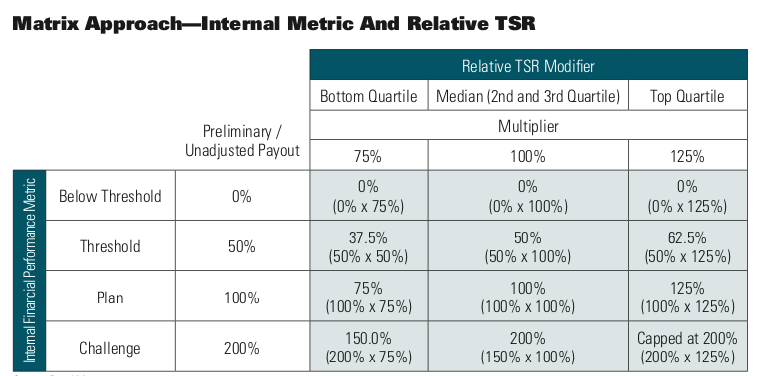

If you could have done better than forecasted, your relative metric won’t payout as well. If you exceeded the forecast but in hindsight that success was easier to achieve than forecasted, the relative metric won’t payout as high. This can be accomplished by two separate measures or by a matrix in which the weighted scores (in the cells) may be weighted more, for example, to absolute TSR.

Consider the payout schedule. Most rTSR plans pay between 150% and 200% of target for rTSR performance at the 75th percentile or above. Beating 75% of your peers is pretty good. However, most plans also pay target for median performance. Institutional advisors and some institutional investors have stated that they do not consider paying target for median performance robust. Threshold performance is often set at the 25th or 35th percentiles and often pays 25% to 50% of target.

Let’s face it—paying 50% of target while underperforming 75% of your peers is probably not aligning pay and performance where 25% of target seems more reasonable. However, if the comparator group includes both direct peers and some general industry comparators, suddenly the median doesn’t look so bad. Having general industry comparators adds ballast. It’s harder to achieve higher relative performance when the sector is down, easier when the sector is up relative to the general market.

Explore using a modifier. A modifier based on relative performance can ensure payout is not inappropriate. If performance compared to the comparator group is high, payout may be higher. If performance is lower, payout is cut back.

Having a two-way dialogue is key

To be successful, there must be a two-way dialogue between companies and investors to ensure that everyone is on the same page. That’s because in an underperforming sector that’s paying target or above target awards to executives, messages are rarely straightforward.

Business results need to be put into proper context. Complex concepts need to be broken down and explained, and the rationale for payouts needs to be bulletproof. Even the best-written proxy statement would not mitigate the risk of messages being open to misinterpretation.

Because incentive plans send strong messages to stockholders and potential investors about what is important to the company, stockholder outreach should be a top priority. Stockholders should greet invitations from boards and senior management to engage in conversations with open arms—even when things on the surface seem clear cut. These are the opportunities for everyone with a stake in the value of a company to discuss performance targets, debate their reasonableness and gain consensus that forecasted performance goals are worth target payouts.

These discussions should be summarized in proxy statements disclosures as a recap of who was involved in the discussions (directors, senior management, investors, etc.), when/how many conversations took place, what was heard and what was changed (or not) as a result. This not only keeps a history of the feedback and response but also demonstrates a level of ongoing involvement between companies and their stockholders beyond say-on-pay.

Moving forward

Setting performance targets isn’t easy in a static environment. Throw in commodity prices and a pandemic, and it becomes that much more difficult. But taking a balanced approach with absolute and relative metrics and communicating your intentions can help safeguard both executive and investor interests.

While it may be a bit more time intensive to design such a plan, it will align incentive payouts with the stockholder experience and will ensure executives’ opportunities are reasonable through the economic cycle. (Don’t forget they have alternatives.) With thresholds that are achievable and safeguards that help avoid unintended consequences, the company is much better positioned overall to survive and thrive through all the unpredictable cycles to come.

Mark Rosen is a managing director in Pearl Meyer’s Charlotte office. He has consulted on executive and board compensation issues for more than 20 years for a broad range of public companies, as well as tax-exempt organizations and academic institutions. Rosen has extensive experience with benchmarking, retirement plan design, governance issues and tax and accounting considerations. Rosen holds a BBA and an MS in accounting with a specialty in Taxation from Texas A&M University and is a Certified Public Accountant.

Sharon Podstupka is a principal in the New York office of Pearl Meyer. Across a wide range of industries she develops internal communications that educate and engage people in their pay programs. She has extensive experience in developing critical shareholder communications that clearly explain pay-for-performance in the context of today’s challenging say-on-pay environment. Her key areas of expertise are communication strategy, stakeholder management and content development. Podstupka holds a BFA in communication arts from New York Institute of Technology, Old Westbury.

Recommended Reading

BP Restructures, Reduces Executive Team to 10

2024-04-18 - BP said the organizational changes will reduce duplication and reporting line complexity.

Matador Resources Announces Quarterly Cash Dividend

2024-04-18 - Matador Resources’ dividend is payable on June 7 to shareholders of record by May 17.

EQT Declares Quarterly Dividend

2024-04-18 - EQT Corp.’s dividend is payable June 1 to shareholders of record by May 8.

Daniel Berenbaum Joins Bloom Energy as CFO

2024-04-17 - Berenbaum succeeds CFO Greg Cameron, who is staying with Bloom until mid-May to facilitate the transition.

Equinor Releases Overview of Share Buyback Program

2024-04-17 - Equinor said the maximum shares to be repurchased is 16.8 million, of which up to 7.4 million shares can be acquired until May 15 and up to 9.4 million shares until Jan. 15, 2025 — the program’s end date.