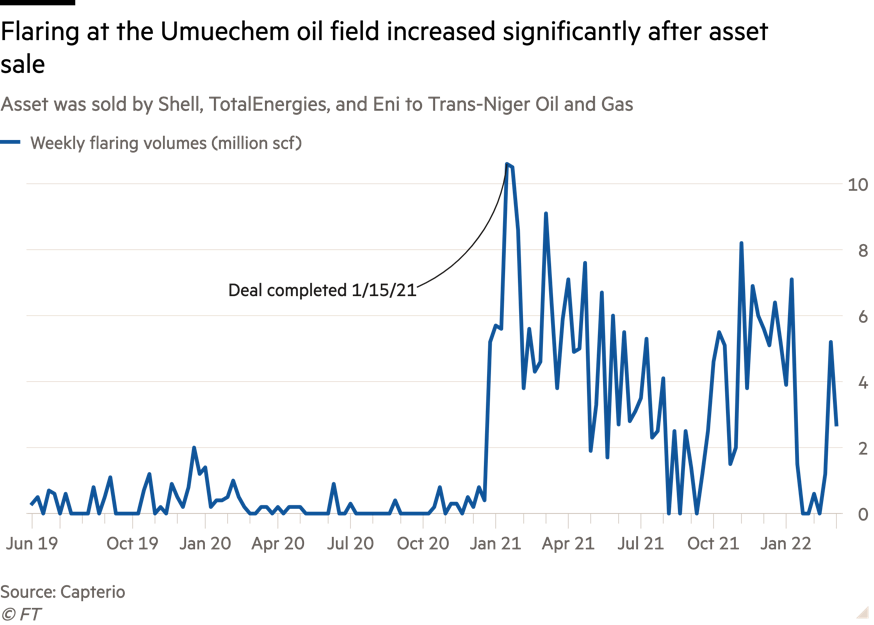

In the case of Shell, TotalEnergies and Eni’s oilfield sale to Trans-Niger Oil and Gas, a private operator, a report found that flaring activity increased over 700% after the deal was completed, increasing CO₂ and methane emissions. (Source: HungryBild / Shutterstock.com)

As oil and gas majors make new climate commitments, they’re dumping billions in dirty assets to private, less climate-friendly operators.

A new report by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) looked at oil and gas deals over the past five years and found assets are increasingly moving away from public companies to private operators without climate commitments.

It’s a trend that raises a pressing question: when a company sells its dirty asset, is it doing anything for the climate—or is it just another greenwashing move to clean its own portfolio?

The EDF data are stark. From 2017 to 2021, more than twice as many transactions moved assets away from companies with net zero targets, flaring commitments and methane goals than the reverse.

“We’re losing disclosure, we’re losing targets, and wells are ending up in the hands of operators that have no intent to safely decommission them at the end of their life,” said Andrew Baxter, director of energy transition at EDF and one of the authors of the report.

Today’s EDF report confirms and quantifies a long-suspected problem in oil and gas asset sales. While selling assets to private companies will clean up public companies’ portfolios, it comes at the expense of weakening climate governance and risking an increase in emissions.

In the case of Shell, TotalEnergies and Eni’s Umuechen oilfield sale to Trans-Niger Oil and Gas, a private operator, the report found that flaring activity increased over 700% after the deal was completed, increasing CO₂ and methane emissions. Unlike the previous owners, Trans-Niger Oil and Gas has made no commitments to cut that pollution.

“That has real-world implications for the energy transition and all the people that live near the oil and gas wells,” said Gabriel Malek, project manager at EDF.

Eni said it did not consider asset sales to be a tool to reduce emissions. The company pointed out it was not the operator of the field, but that it was collaborating with EDF and its peers “to promote adoption of clauses related to methane emissions reduction and reporting criteria.” Eni has made commitments to reach zero flaring by 2025 as part of its strategy to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

“When considering divestment, Shell carries out due diligence on potential buyers to evaluate their financial health, safety record and overall operating capabilities,” said a Shell spokesperson. The company added that before a transaction closes, regulators have the final say on the buyer’s ability to safely and responsibly operate the asset and meet emissions requirements.

Oil and gas operators sell assets for many reasons, including to boost cash flows to pay for dividends and share buybacks, to pay off debts, or to raise money to spend on clean energy projects. Cleaning the portfolio is a more recent motivation.

Traditional oil and gas dealmaking may not be compatible with a net zero world, argue the EDF authors. Ensuring safeguards are in place when private operators take on assets will be important to close this transferred emissions blind spot.

To ensure climate stewardship endures beyond the deal’s completion, the authors of the report recommend rules requiring climate disclosure commitments from private buyers, applying the same emissions-reduction standards even after the asset is sold, and ensuring buyers can afford to decommission wells at the end of their life.

“Once these assets move off the books, it’s going to be very difficult to get them on the books again within public disclosure and public scrutiny,” Baxter said.

Recommended Reading

Excelerate Energy, Qatar Sign 15-year LNG Agreement

2024-01-29 - Excelerate agreed to purchase up to 1 million tonnes per anumm of LNG in Bangladesh from QatarEnergy.

UK’s Union Jack Oil to Expand into the Permian

2024-01-29 - In addition to its three mineral royalty acquisitions in the Permian, Union Jack Oil is also looking to expand into Oklahoma via joint ventures with Reach Oil & Gas Inc.

Permian Resources Continues Buying Spree in New Mexico

2024-01-30 - Permian Resources acquired two properties in New Mexico for approximately $175 million.

Eni, Vår Energi Wrap Up Acquisition of Neptune Energy Assets

2024-01-31 - Neptune retains its German operations, Vår takes over the Norwegian portfolio and Eni scoops up the rest of the assets under the $4.9 billion deal.

NOG Closes Utica Shale, Delaware Basin Acquisitions

2024-02-05 - Northern Oil and Gas’ Utica deal marks the entry of the non-op E&P in the shale play while it’s Delaware Basin acquisition extends its footprint in the Permian.