First, Benjamin Shattuck of Wood Mackenzie disagrees with accusations that the U.S. oil and gas sector has not responded to the elevated global demand for energy.

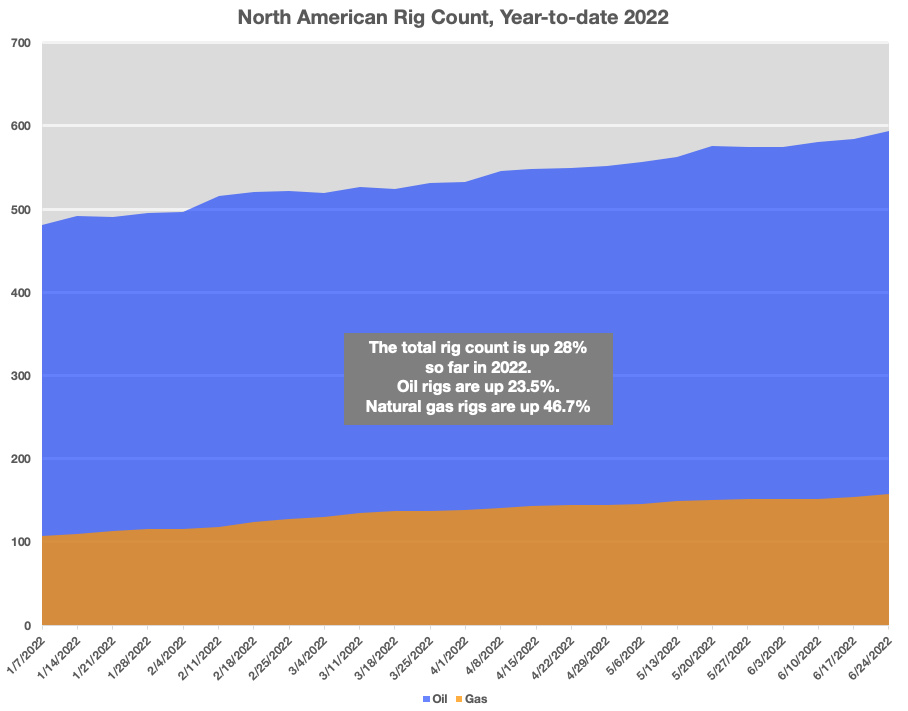

“Obviously, the rig count has increased,” Shattuck said at a recent industry event.

The North American count is up 28% so far in 2022, with oil rigs rising 23.5% and natural gas rigs a whopping 46.7%, according to the Baker Hughes weekly data.

Still, the U.S. upstream sector has lost some of its 2015-2019 shale boom swagger.

At a recent quarterly oil markets event hosted by Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, WoodMac’s research director for Americas upstream oil and gas said that, after spending 130%-140% of cash flow on an annualized basis in the 2010s, “we came into this decade with, effectively, a financial hangover. After years of talking about capital discipline, we started to see some of that being implemented in the end of ’19 coming through ’20.”

Outlier years

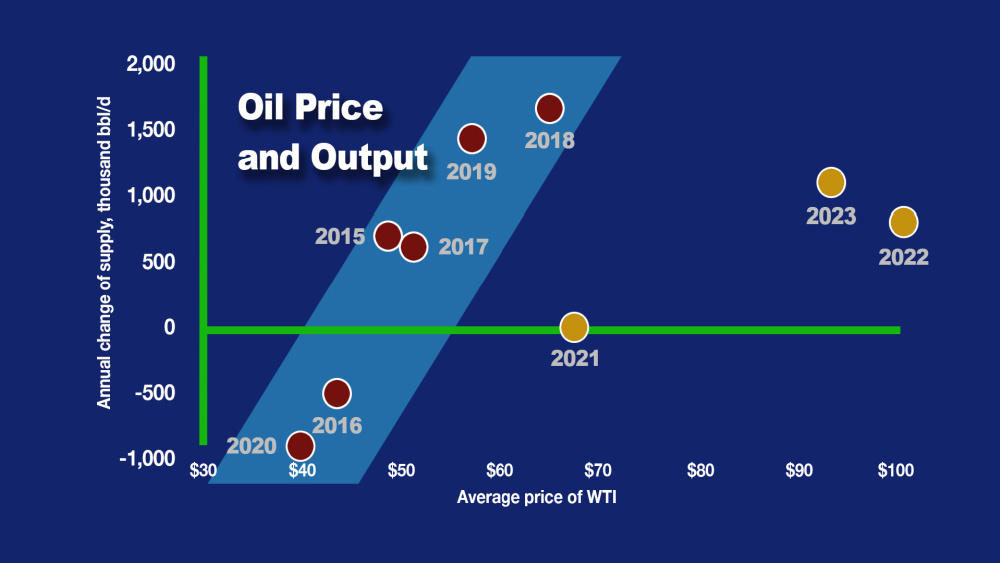

The divergence can be seen in the chart below, which is based on the graphic produced by Wood Mackenzie’s research team and discussed by Shattuck at the event. This chart was created by Hart Energy based on data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

The key is to understand that the chart is not chronological.

The x-axis represents the average annual price of a barrel of WTI. The y-axis represents the change in WTI production from year to year. So, to plot 2015, subtract 2014’s average daily output (about 8.75 MMbbl/d) from 2015’s (about 9.4 MMbbl/d) to get 650,000 bbl/d. The average price for the year was $49/bbl, so the vertical is 650, the horizontal is 49.

“For all of last decade, there was a pretty tight correlation between oil price and output from the shale sector,” Shattuck said. The pattern ended in 2021, and the outliers continued through this year and projections for next year.

“These are representative, obviously, of unprecedented circumstances within the space, but they also represent a shift in mindset that we think is structural in the sector moving forward,” he said.

That mindset belongs to the oil and gas sector’s investors.

Keep showing ’em the money

“Investors want every single penny of excess cash flow given back to them after a decade where that largely did not happen,” Shattuck said.

The sentiment is understandable, but how does the oil and gas sector return to growth? And should it? Investors, he said, would say no.

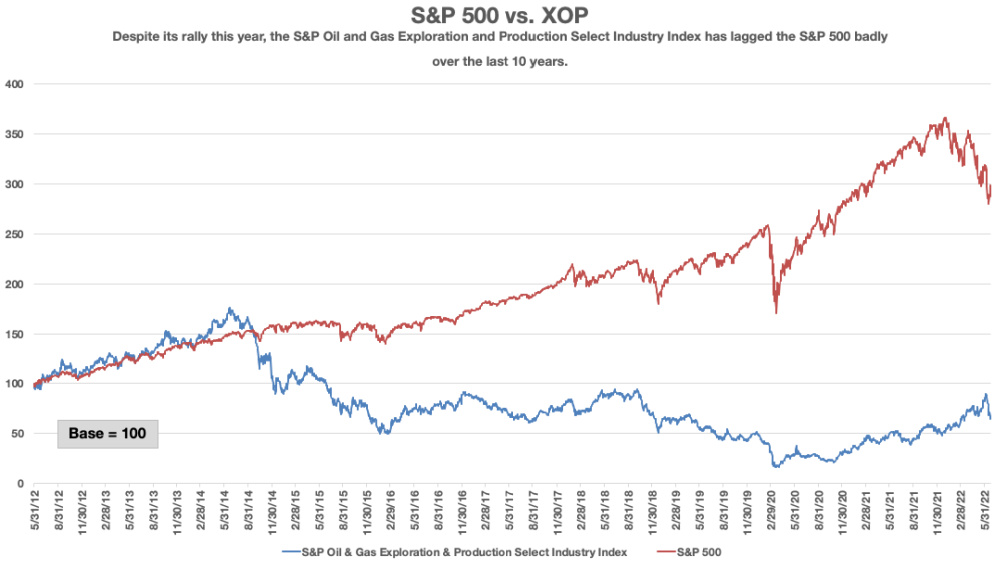

“The reason investors don’t want that to happen is every time title grows too fast, returns are driven downward,” he said. “If you were to track the XOP (S&P Exploration and Production EFT) … from 2008 until today, it’s in negative territory.

The chart below tracks the XOP and the S&P 500 since 2012. XOP fell below its starting point in 2014 and has never recovered, despite an extended rally that began in late 2020. The rally extended into second-quarter 2022.

“Investors, especially generalists, are myopic on the compounded annual return,” Shattuck said. “The No. 1 thing that has drawn the XOP down, that draws any equity down, is big downward movements.”

And, boy, have there been big downward movements. Oil is the only major commodity in the world that’s crashed three times since 2008, Shattuck said. In the minds of investors, he said, those oil price crashes have been largely associated with oversupply driven by outperformance, or overproduction from the shale patch.

Sorry, but size matters

The thing is, you can’t grow oil and gas production to meet rising demand without, well, growing production. And you need investors on board to do that.

“What ultimately needs to happen, then, investors need to come to a mindset where they feel that tight oil and OPEC, or the global market, can work in a less volatile manner,” Shattuck said. “How can that happen? Through a consolidation of the industry.”

This isn’t necessarily an unfamiliar concept. Some of the bigger players in the oil and gas sector have contended that in the future, only companies in the $10 billion-and-up club will be investable in the Permian Basin. That’s not Shattuck’s view, but he agrees that a universe of fewer, larger oil and gas companies will increase the comfort level of many investors.

“Fewer, larger companies make investors more comfortable that we won’t overshoot or undershoot in terms of the oil price signal,” he said. “It’s a sustainable business model before tight oil and ultimately is a more predictable and stable contributor to global oil markets.”

Recommended Reading

TPH: Lower 48 to Shed Rigs Through 3Q Before Gas Plays Rebound

2024-03-13 - TPH&Co. analysis shows the Permian Basin will lose rigs near term, but as activity in gassy plays ticks up later this year, the Permian may be headed towards muted activity into 2025.

Chevron Hunts Upside for Oil Recovery, D&C Savings with Permian Pilots

2024-02-06 - New techniques and technologies being piloted by Chevron in the Permian Basin are improving drilling and completed cycle times. Executives at the California-based major hope to eventually improve overall resource recovery from its shale portfolio.

US Gas Rig Count Falls to Lowest Since January 2022

2024-03-22 - The combined oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, fell by five to 624 in the week to March 22.

CEO: Continental Adds Midland Basin Acreage, Explores Woodford, Barnett

2024-04-11 - Continental Resources is adding leases in Midland and Ector counties, Texas, as the private E&P hunts for drilling locations to explore. Continental is also testing deeper Barnett and Woodford intervals across its Permian footprint, CEO Doug Lawler said in an exclusive interview.

To Dawson: EOG, SM Energy, More Aim to Push Midland Heat Map North

2024-02-22 - SM Energy joined Birch Operations, EOG Resources and Callon Petroleum in applying the newest D&C intel to areas north of Midland and Martin counties.