Presented by:

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the March 2021 issue of Oil and Gas Investor magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

The first meeting between three top executives of global oilfield services (OFS) giant Schlumberger Ltd. and three top executives of leading U.S. pressure pumper Liberty Oilfield Services Inc. occurred in a restaurant in New York City in late 2019—and certainly before COVID-19 closed down the Big Apple in March 2020. Schlumberger initiated the invitation. On the menu: Big Blue’s OneStim hydraulic fracturing division.

It was no secret that the French OFS provider was looking to sell so-called noncore businesses, particularly those in U.S. shale, which was undergoing a swoon in activity as E&Ps were pulling back on activity due to Wall Street capital flight. But it was barely two years after it had paid $430 million to Weatherford International for its frac fleet.

One company’s noncore is another’s transformation.

That first gathering was informal and casual, according to Liberty chairman and CEO Chris Wright, but crucial nonetheless.

“We talked about life and our outlook on business. I found their leadership open, candid, just full candor, which certainly inferred trustworthiness,” he said. “That’s the way Liberty does business. If people are honest and open, you can find solutions. So it began with just humans connecting, and that connection built confidence on both sides.”

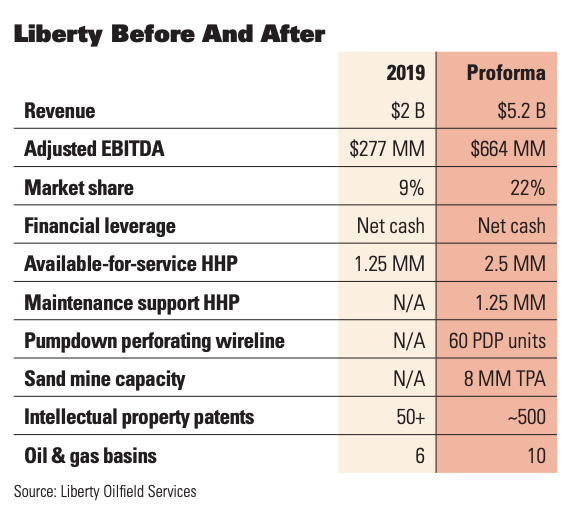

The deal closed on New Year’s Eve, more than a year later, with Schlumberger taking all equity for its OneStim division with a 37% ownership stake in Liberty. Analysts valued the deal at $448 million at the time of the announcement in September. Liberty gained some 3.5 million hydraulic horsepower, along with 60 wireline perforating units, two Permian sand mines and a basket of technologies. The Denver fracker more than doubled in size and capacity overnight.

While Schlumberger was founded nearly a century ago, Liberty is just a decade old. Wright and his executive team—still intact—formed the company in 2011 with the goal “to be the best damn frac company, period.” And although it has become the largest frac-only company onshore U.S.—second only to Halliburton when comparing all service companies—its focus on innovation and entrepreneurship gives it a much smaller feel.

“We embrace decision-making near the tip of the spear,” he said. “As we’ve taken a step to get even bigger, I’m convinced we will keep that scrappy young, hard driving, innovative culture we have.”

Wright himself features an impressive bio. He holds a mechanical engineering degree from MIT and graduate work in electrical engineering at both MIT and University of California – Berkeley. During his career, he’s worked in nuclear fusion, solar and geothermal energies. He started and remains executive chairman of both a private E&P, Liberty Resources, and a private midstream company called Liberty Midstream Solutions.

In the early part of his career, at 27, he formed Pinnacle Technologies, a hydraulic fracturing mapping company that was instrumental in cracking the code for shale in the 1990s. Besides all that, he’s an avid outdoors enthusiast. Oil and Gas Investor caught up with Wright in the midst of a road tour in which he was visiting OneStim field offices.

Investor: What was the compelling reason for pursuing the OneStim deal?

Wright: It was unique. M&A generally has not been a primary focus for Liberty; we’ve been very much an organic grower. But when Schlumberger approached us, given the quality of the company, the technology, the low turnover and high-quality employee base, we were interested in that dialogue.

If you pick the three big investors in downhole technology in the frac world, it’s Halliburton, Schlumberger and us. They’ve been at it longer than us developing modeling technologies to understand what goes on downhole in reservoirs, equipment technology, process automation and software. So they brought a lot more than horsepower. They brought a number of technologies and an experienced workforce that we thought could be a great fit at Liberty, and it could be quite additive putting these

forces together.

But we still tread lightly. Acquisitions are risky, particularly in people or culture-based businesses like service companies.

Investor: Why was the deal arranged as an all-equity transaction?

Wright: This was pre-COVID, but both sides recognized that the market was tough and getting worse. The best way to achieve both of our ends—which is to make a better, stronger frac competitor—was to do it in a full partnership deal, which meant all equity. Schlumberger didn’t want to sell for cash at the bottom of a market. They wanted to contribute what they had invested decades in building into a place where they thought that they could realize the full value of not just that business, but the combined business with time. So with equity you no longer have to worry about where are we in the cycle; it’s only about relative value.

Investor: The valuation was significantly less than estimates of what Schlumberger had invested in that division. How important was the timing of the deal?

Wright: The announced acquisition price was just how many shares are we going to issue the day of the acquisition and what was the share price that day. Analysts wrote a value for the transaction that it was announced on that day. But it was basically a long dialogue on what are the right trade-offs and how do we make up a business going forward that’s going to be worth more. There’s no simple formulaic way to do that.

We did one other deal in our history that was also at the bottom of a downturn. We bought the Sanjel assets in 2016 that was basically a bankruptcy auction. We used cash and bought assets at the absolute cheapest time. We knew a rebound was coming, and we’d grown market share a lot. So the Sanjel deal worked because the timing was good, both on the price we paid and on the spare capacity it gave us to come out of that downturn.

In this case, we didn’t have a distressed seller. We had the world’s biggest, most valuable service company as the seller. We had a seller that realized the compelling industrial logic of combining two of the best players in the space to get synergies of a larger scale and to get the focus of Liberty’s management team.

Schlumberger is in many business lines. They’re global around the world while Liberty is focused on North America and fracking. All we do is frac. So that was a way to get the most value out of the assets. And if you’re a strong seller, you don’t want to sell for cash at a bottom, but you’ll take stock if you believe in the future of the business going forward. So I think that structure of the deal made sense for Liberty’s balance sheet, and it made sense for Schlumberger.

Investor: Holding a large equity interest in Liberty, what is your relationship with Schlumberger going forward?

Wright: We’re aligned, and it will continue that way because they are a large shareholder and we also added two board members from Schlumberger. As far as industry knowledge in technology in the space, we added capability there. And also we’re no longer competitors. We provide frac, wireline and services in the United States and Canada; Schlumberger doesn’t.

But they are still massive investors in reservoir technology and optimization in business processes. Beyond the deal, we’re launching a technical cooperation partnership going forward, so that the things Liberty developed that have broader application than just for frac, we’re going to share with Schlumberger. And as Schlumberger develops technologies that will add value to Liberty’s businesses, we’re going to use those technologies and do some things jointly together. So it’s a transaction that puts all the frac assets under Liberty management and a technology development partnership going forward.

SIDE BAR:

DEEP AND WIDE

Well interference issues plagued operators across many basins the past couple of years as they overshot on tightening well spacing in an attempt to maximize recoveries. Although Liberty’s frac fleets arrive on pad after the wells are spaced and drilled, its WellWatch technology assures the most reservoir will be drained per the situation—and provide guidance for drilling the next pad over.

WellWatch monitors pressure in offset wells in real time while a well is being pumped.

“If the fracture size is getting closer earlier on than it was expected to, at this point we can drop some far-field diversion and try to minimize the parent/child interactions while maximizing the reservoir stimulation,” Liberty Oilfield Services CEO Chris Wright said.

Operators have defensively “solved” well interference by locating wells so far apart that they won’t interact, but then the oil between those two wellbores never gets developed, he noted.

“Generally, that’s a good idea, but when you do that, you’ve got to optimize the size of your frac so that you still get close enough so you don’t leave a lot of oil behind,” he said. “And you don’t want too much overlap on the frac systems because then you have much reduced quality of wells because they’re spaced too close together. But you want to have a little bit of interaction so that you don’t leave a lot of undrained oil between those wells.”

While Liberty historically employs near-wellbore diverters, Wright is excited about the addition of Schlumberger’s far-field diverter called BroadBand, which controls the end of the frac wing. “We’ve been using that already,” he said.

Optimizing perforation cluster design is another area of emphasis for Liberty. Operators generally want to shoot too many perforations, Wright said, but too many perforations in pipe results in a loss of control over where the fluid is going. Too many clusters create robust IP but a quick fall off from cluster interference. Too few clusters cause fracs to grow too long and into the nearby wellbore, leaving oil behind between the clusters.

“It’s not just ‘is it a 500,000-pound stage or 700,000-pound stage?’ It’s where those 700,000 pounds are going to go. And so clustering, which are those individual fractures you create within a frac stage, matters a lot.”

Liberty makes it a practice to publish a great deal of its findings.

“Our dream is to make the whole industry better,” Wright said. “Obviously, we want Liberty customers to have the best advantage, but we love the shale revolution, and we want to see it keep getting better.”

Investor: What kind of information do you expect will benefit Liberty coming from Schlumberger?

Wright: Schlumberger has done a lot in data analytics, in monitoring, in software platform-based technologies that they’re developing for a broader suite, but they certainly have application in frac. We’re developing next-generation technologies for our business that will also have applications in other Schlumberger business lines.

Investor: Will they have a say in how and where you conduct business?

Wright: Absolutely not. To their credit, they didn’t want that. Schlumberger recognized that while they developed a lot of great things and had a lot of great people, they were a big company and didn’t have their focus on North American frac. Therefore, they were maybe not as agile, not as lean and mean as they needed to be to be the top player in frac.

And they recognized that Liberty is the top player in frac. They understood that Liberty rolls differently than they do. They understood the way to win is to combine these assets under a team that’s been winning, that’s very entrepreneurial, very fast moving, very focused on frac.

And it was critical to Liberty that we not change the way we operate, the way we make decisions, the way we interact with our customers. That was not a deal that Liberty would have done, but it was also not a deal that Schlumberger wanted.

Investor: How does it feel to double in size overnight?

Wright: It’s exciting, but it’s also humbling. We’re swallowing a whale, and we’ve got to be careful and thoughtful in the way we do this. Schlumberger OneStim had areas where they were better than Liberty, and we’ve got to learn those things and adopt them at Liberty. And then there are things that Liberty does that are better than [the way] Schlumberger did them. And we’ve got to slowly roll those out across all of the fleets. We’ve got to bring two proud organizations into one organization and that takes some time.

We closed the deal on New Year’s Eve, but it doesn’t make everything all one family immediately. The biggest risks and the biggest upside of these transactions is always on the human side.

Investor: How will OneStim fleets be worked into your operations?

Wright: On January 1, they were running exactly how they were running on December 31, and in large part that’s still true today. Their fleets in their basins are being run by the same crew leaders and the same regional management. In the Permian, things will be folded under one team pretty quickly. In the Haynesville, Oklahoma and Canada, the Schlumberger leadership is still leading in those districts.

So we’re going to do it humbly and with some time before we go out and say stop doing that and do this. We want to understand what they’re doing and why, and then they’re going to visit our crews. In the interim we’re calling it Liberty red and Liberty blue to facilitate the learning process, but as quickly as we can, it’s just going to be Liberty.

Investor: Are you taking any iron off the market following the integration?

Wright: One million horsepower is being permanently retired, and a little more than a million horsepower is just parked and no longer being actively marketed. The only fleets that are running today are the fleets that were running before the deal closed. So we are status quo right now.

The million horsepower being retired was idle, older equipment that we thought the investment to bring it up to Liberty standards was just too large of an investment. It was basically obsolete equipment. The other million and a quarter of horsepower that we’re no longer actively marketing is just to right size the available capacity for what we see as the size of the market opportunity out there.

Until COVID, all of our fleets were busy all the time. That limited our ability to enter a new basin. For the first time in our history we have an enormous amount of ready-to-go equipment that’s idle—and we like that. It’s optionality to pursue opportunities when they make sense.

Investor: What’s your viewpoint of future horsepower demand?

Wright: In the summer of 2018, there were over 400 fleets running. We don’t think the industry will ever see 400 fleets again. In fact, we would be surprised to see the industry ever hit 300 fleets again.

That’s for two main reasons. One is enormous efficiency increases in fleet throughput. I would say Liberty has been a significant driver of that across the industry. We’ve always been driven to figure out how to do something more efficiently with the same amount of equipment [and] the same amount of humans to get more done in a day. That leads to a lower cost to produce a barrel of oil, a smaller time on location, lower environmental impact and lower safety risk.

The other is capital discipline and reduced rates of investment among the whole North American E&P shale universe. Our industry has had a very tough decade. The shale revolution saw a flood of capital come into our industry pretty much like the start of the internet boom did, with overinvestment, undisciplined investment, a lot of destroyed capital and a lot of weaker companies. Now, a shakeout is happening.

In fact, I would say we’re well along the way to where we’re going to come out the other side with a smaller number of players that are more disciplined, more ESG conscious and more profitable. I think our industry is going to have a much better decade in front of us than we did behind us. And all of those things are leading to the total fleet count over the next four or five years that likely never reaches 300.

Most of the public companies’ goals are to have their December 2021 production roughly flat from their December 2020 production, so sequentially to keep the end-of-the-year exit rate flat. Our estimate is 200 or maybe a little less active frac fleets are needed to keep U.S. oil and gas production flat throughout the year 2021.

Investor: Liberty now has operations in two dry gas basins, where a year ago you were in none. What does this tell us about your view on natural gas?

Wright: When we began 10 years ago, all of the basins that we entered until a few months ago were all oil dominant basins. We were basically bullish on activity in the oil basins and bearish on activity in the gas basins. Now we think the reset in the gas basins has happened. Activity levels of the major gas basins going forward today are probably still just flattish—we don’t expect screaming growth, maybe a little bit—but flattish or a little bit of growth is a much better marketplace than the significant contraction in activity there over the last decade.

We’ve looked at long-term global LNG capacity growing maybe 5% or 6% per year for the next five or 10 years. That looks good. The U.S. now gets about 40% of our electricity from natural gas, so we’ve just massively changed our electrical sector faster than people could have believed.

But the rest of the world’s electricity production is still completely dominated by coal. The best way to move that forward, as far as lowering particulate matter emissions, which are the most deadly emissions today, and lower greenhouse-gas emissions is to switch more of that to gas. A lot of it will go to wind and solar as well, but they need gas. And at the scale we’re talking, I think gas will be the biggest player there. So we like the multidecade outlook for gas, and we’re thrilled to be establishing operations in all the major gas basins.

Investor: Are you concerned about headwinds from new government policies flowing down to the OFS sector?

Wright: Oh, without a doubt. It’s not a shock to hear the moves on federal lands. But it’s still a disappointment, and to have it done on day one as if there are no trade-offs to be evaluated, it was definitely disappointing. I wrote an editorial on why a ban on drilling on federal lands actually will increase greenhouse-gas emissions and increase air pollution.

So it’s hard to argue from facts that that’s a positive thing. In fact, it’s pretty clearly a negative thing both for the environment and for U.S. workers and U.S. businesses. Whenever a policy is made because it pleases a certain group or it feels good, not because a rational evaluation makes it good, that’s scary. But of course that’s politics. We don’t expect a radical change in what’s going to happen in the industry in the short term, but there certainly could be forces from the new administration on the regulatory front that build increasing headwinds.

Investor: What feedback are you receiving from the investment community? Are they demanding any reformations with OFS companies’ business models similar to E&Ps?

Wright: Yes. The investor base just wants rational decisions made based on the changing landscape. I think their frustration is that a lot of times management teams look backward and are not proactive enough about what’s coming in the future. The investor community in general focuses on the same two big things that we focus on, and front and center is return on capital employed. Are the investment decisions being made likely to lead to an attractive return on capital employed? That’s I think at the base. That’s their job and that’s our job.

“It’s not a shrinking industry. It’s a mature industry that’ll likely continue to have slow growth going forward so that the remaining third of humanity also gets modern energy and better lives.”

The other is an increasing social desire. The new generation is growing up in the wealthiest situation the world has ever seen. And it’s very important to them that they feel that businesses are doing everything they can to help the environment get better and to lift people up that were born in unfortunate circumstances. That is at the foundation of our business: how can we better human lives? Broadly, how can we be part of the solution, using our technology, equipment and passionate team to bring affordable, reliable and sustainable energy to people around the world?

Investor: How do you see the role of oil and gas in an energy transition?

Wright: There is a widespread belief that we’re in the midst of an energy transition that’s going to make us all obsolete. Some people say 10 years and others maybe 20 or 30 years. That’s just not going to happen. It’s not realistic.

The arrival of oil and gas completely transformed the lot in life of the average person in the world. Global life expectancy went from 30 or so years to 72 in a few generations. The number of people living on the equivalent of less than $2 per day went from 90% of humanity to today 9% of humanity and falling. That 9% is still 700 million people, and they want to make the energy transition too. They want to have lives like you and I.

So to me it’s about energy access. We still have a boatload of humanity that cooks their meals by burning wood, dung and agricultural waste. It’s deadly, and it shrinks the opportunities and lifespans of the people living like that. So to me, the biggest issue today is finishing that energy transition and getting everyone to have longer, healthier lives.

Wind and solar today provide less than 3% of global energy after 20 years and $2 trillion of subsidies. They’re not likely to displace all the other energy sources. Nuclear and geothermal might have a renaissance. A lot’s going on in energy storage. But energy systems transform slowly, and the advantages of fossil fuels are so compelling today that I think it’s a safe bet they will still be the dominant source of energy when I die.

But they’ll be cleaner and there will be a different mix among them. We may have widespread carbon sequestration. We may be burning natural gas in Allam Cycle plants, which is a high-pressure, enriched oxygen, supercritical CO₂ cycle. The only byproducts are water vapor and high-pressure CO₂, which could be immediately injected underground. This is low cost, abundant, reliable, carbon-free electricity generation.

It’s not like the sun is soon setting on fossil fuels; the math and the physics say that’s not going to be happening. Looking at the EIA [U.S. Energy Information Administration] data, the percent of total U.S. energy that came from oil and gas hit an all-time high in 2019 at 69%. It’s not a shrinking industry. It’s a mature industry that’ll likely continue to have slow growth going forward so that the remaining third of humanity also gets modern energy and better lives.

I love all kinds of energy. I’m not saying it’s never going to change. It’s going to change. It’s going to evolve, but most of the beliefs people have are just not consistent with history, with the numbers and with physics.

Investor: What’s your prognosis for shale plays going forward?

Wright: As demand for oil and gas rebounds, the world is going to need American oil and gas. The world is going to need growth in American oil and gas from where we are right now, at about 11 billion barrels of oil per day. We were growing too fast before and we hurt world oil markets, and we certainly hurt returns of our companies. But I think this new discipline of keeping production flat at where we are—I think in one, two, three years out, the world will need us and oil prices will be that message.

There’ll be a call on more oil and more natural gas from the U.S., and I believe the new, smaller, leaner meaner industry will be able to meet that demand, but hopefully in a measured way with U.S. production growing a few hundred thousand barrels per day per year, not a million plus barrels per day per year.

But, you know, people have been talking about the end of U.S. shale since soon after it started. I’m quite optimistic about it. I think that over the next few decades, U.S. shale will be a very meaningful resource for world oil demand and for natural gas and natural gas liquids demand.

Investor: What role did you play in the early development of shale technologies?

Wright: Yeah, a bit of a blind squirrel finds nut. I had started a company called Pinnacle Technologies in 1992, and in the mid-’90s we started realizing that if you refracked a well that already had been fracked, that production itself would change the stress state of the rock, and you might get a fracture growing in a different direction. So you could touch new rock. We ultimately developed models of multiple fractures and how they interact with each other, because our goal was how do you touch more reservoir rock?

[Mitchell Energy’s] Nick Steinsberger, who I think is enormously important to the start the shale revolution, saw me give a talk about these ideas in East Texas, and he said, ‘Come to Fort Worth,’ and I met the team at Mitchell there.

Mike Mayerhofer, who’s a long-time colleague of mine, was at Pinnacle 23 years ago and he’s at Liberty today. Mike is maybe the most important technical pioneer in the way he was doing these very large slickwater fracs instead of crosslink gel fracs in East Texas in the Cotton Valley and Travis Peak. He was getting some success—meaning better gas production and cheaper well costs—but not understanding why they were working with so little sand placed.

So these ideas kind of came together in the very early Mitchell first slickwater fracs in the Barnett Shale in vertical wells with Mayerhofer’s frac idea and Pinnacle’s tiltmeter and microseismic mapping technologies to see if we were indeed getting network fractures. And by great luck we were. If you can touch a huge contact area of rock, then you can produce hydrocarbons from very low permeability rocks like shale.

I was lucky to have some ideas and some input and be a blind squirrel at the start of the shale revolution. I had no idea how big it would turn out to be at that time. I think it’s been great for not just the oil and gas industry, it’s been great for the world in collectively lowering the price of oil, natural gas and propane, which is the bridge fuel lifting folks out of energy poverty.

Investor: What’s your favorite experience as an outdoors enthusiast?

Wright: I like to go to remote places. Climbing to the top of Mount Chimborazo in Ecuador with my wife in socked in weather with no visibility would be high on that list. More recently there was a pretty remote waterfall called Cedar Falls a couple of mountains behind my house in Montana, so a combination of ski and rappel, traveling back there to climb that frozen waterfall was also a great achievement.

But the most spectacular climb I did was in Alaska with my wife. We never even made the top of the mountain, but we had an awesome few days on a peak in Alaska.

Recommended Reading

EIA: Permian, Bakken Associated Gas Growth Pressures NatGas Producers

2024-04-18 - Near-record associated gas volumes from U.S. oil basins continue to put pressure on dry gas producers, which are curtailing output and cutting rigs.

Benchmark Closes Anadarko Deal, Hunts for More M&A

2024-04-17 - Benchmark Energy II closed a $145 million acquisition of western Anadarko Basin assets—and the company is hunting for more low-decline, mature assets to acquire.

‘Monster’ Gas: Aethon’s 16,000-foot Dive in Haynesville West

2024-04-09 - Aethon Energy’s COO described challenges in the far western Haynesville stepout, while other operators opened their books on the latest in the legacy Haynesville at Hart Energy’s DUG GAS+ Conference and Expo in Shreveport, Louisiana.

Mighty Midland Still Beckons Dealmakers

2024-04-05 - The Midland Basin is the center of U.S. oil drilling activity. But only those with the biggest balance sheets can afford to buy in the basin's core, following a historic consolidation trend.