Presented by:

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the June 2021 issue of Oil and Gas Investor magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

For thousands of middle-market companies with debt below $100 million, the borrower-lender relationship involves a relatively simple capital structure, with a bank loan secured by a first lien and a mix of preferred and common equity. Such middle-market bank loans typically involve one lead bank, which may partner with a few other banks, and are illiquid investments that are not traded like broadly syndicated leveraged loans for larger borrowers. Middle-market borrowers are typically owner-operated family businesses or portfolio companies of private equity sponsors. Therefore, upon default, neither the lenders nor the owners can readily exit their investment in these private companies, so they must find a negotiated resolution to avoid bankruptcy.

During these negotiations, lenders may find that they enjoy an unfair advantage where the troubled borrower relies on the bank loan for its liquidity to fund day-to-day operations, the owners are unable to invest additional capital and refinancing options are limited. While all parties will generally prefer avoiding bankruptcy, lenders may discover that borrowers’ lack of familiarity with bankruptcy law often makes them deeply concerned about the stigma and risks involved in a bankruptcy filing, which leaves room for negotiation of an out-of-court solution. When lenders overreach at the negotiating table, however, they risk lender liability.

Rights and responsibilities

Equity owners of a business have the right to attend shareholder meetings, vote on strategic directions and/or elect members to the board of directors. The board of directors, in turn, selects officers to manage the day-to-day operations of the business, including hiring employees. For solvent companies, the directors and officers owe fiduciary duties to equityholders, including the duties of care, loyalty and good faith. For insolvent companies, the fiduciary duties of directors and officers flip from equityholders to creditors. The business judgment rule insulates directors and officers from liability as long as they observe their fiduciary duties, thereby protecting them from frivolous lawsuits.

By contrast, a lender forfeits the right to control a borrower’s business in exchange for certain legal rights: liability protection from stakeholders, the right to seize underlying collateral, priority treatment in bankruptcy and predictable cash flows in the form of interest. As long as “the lender-borrower relationship is that of an arm’s length transaction,” lenders typically do not owe fiduciary duties to borrowers and other stakeholders.

However, if a lender acts contrary to its role as a passive investor by exerting excessive control over a borrower’s day-to-day operations or effectively usurping or dominating the management function of the borrower’s business, lender liability risks arise. Lender liability claims could include breach of contract, tortious interference, fraud, equitable subordination and breach of fiduciary duties. In lender liability litigation, a borrower (and creditors harmed by the lender exerting excessive control, such as vendors, counterparties, taxing authorities and other unsecured creditors) may bring causes of action against the lender, and the lender may be held liable for damages, thereby piercing its shield against such liability and jeopardizing its priority treatment in bankruptcy. Courts may consider whether the lender’s conduct was inequitable, caused harm to the borrower’s other creditors or conferred an unfair advantage to the lender.

Facing COVID-19 challenges

Stay-at-home orders driven by the COVID-19 pandemic have severely decreased demand across numerous industries, with the energy industry being hit doubly hard due to a simultaneous OPEC price war in the first quarter of this year. The subsequent decline in oil prices has caused energy companies to face plummeting revenues and diminishing liquidity. With the debt and equity markets largely closed to the energy sector, borrowers are pleading for liquidity from their banks.

The issue is exacerbated by the industry’s decades-long reliance on asset-based lending. In asset-based lending, loan advances are limited to a percentage, called the “advance rate,” of eligible collateral. “Eligible collateral” refers to assets that meet the bank-specified criteria for inclusion in the borrowing base. The “borrowing base” is the total amount of the borrower’s eligible collateral, which may be significantly different from its total collateral due to customer concentration, aged receivables, slow-moving inventory and other factors. This lending model has proven problematic for energy companies because the very asset values that drive the company’s credit lines are collapsing in tandem with oil prices.

A prime example of potentially problematic asset-based lending is “reserve-based lending,” which was popularized in the 1970s amid rising oil prices. Reserve-based lending provides E&P companies with revolving credit facilities that are sized by the net present value of a portfolio of producing assets. Typically, only assets actively producing oil and gas are classified as eligible collateral. The borrowing base is periodically recalculated using updated reserve data and price projections, called a “borrowing base redetermination.” With borrowing bases for upstream oil and gas companies adjusted twice a year to match the latest price projections, banks are notifying energy companies of large deficiencies, meaning that the amount drawn on the revolving line of credit exceeds the amount allowed per the revised borrowing base.

Often concurrent with collapsing collateral values, lenders can further restrict borrowing in multiple, subjective ways: (i) changing eligibility requirements and (ii) changing advance rates. The net result of these two variables may cause the borrowing base to suddenly fall below the borrowed amount. If so, the lender can cause the loan to become overdrawn, putting the borrower in default.

To cure a borrowing base deficiency or overdrawn loan, the borrower needs to pay down the loan, usually in six equal monthly installments, or add more collateral. In other words, the borrower may have been in compliance before the lender redetermined the borrowing base, but then the lender’s new borrowing base calculation may create a surprise deficiency.

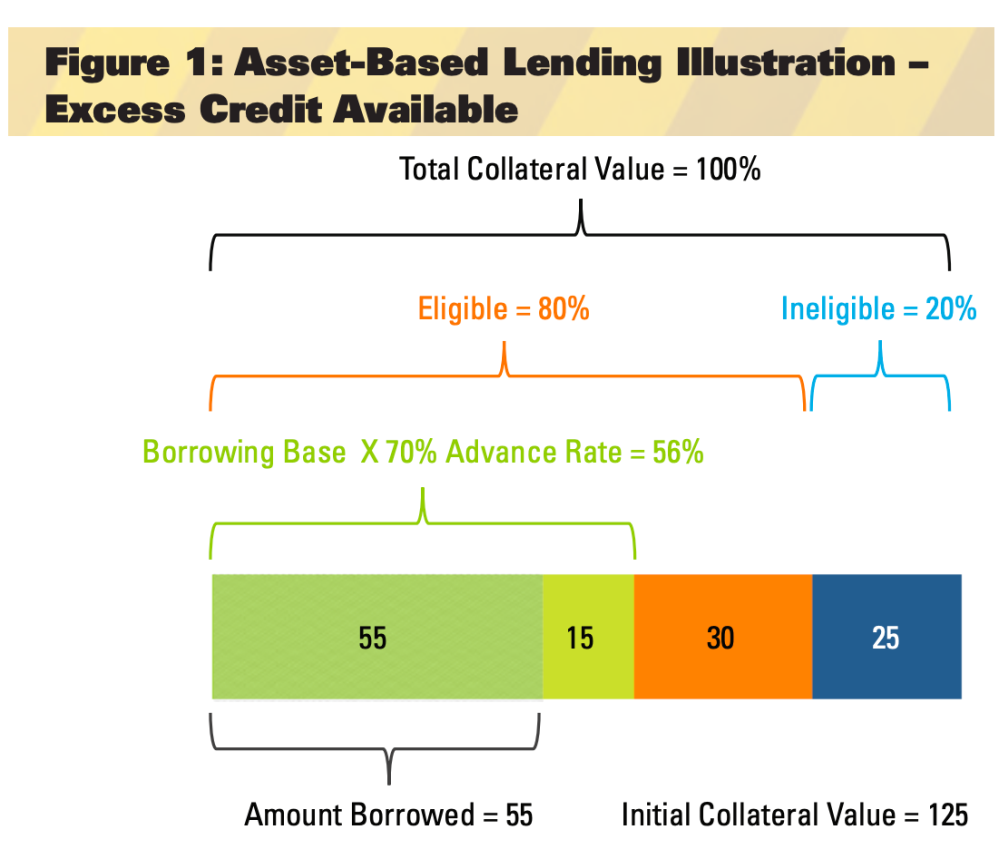

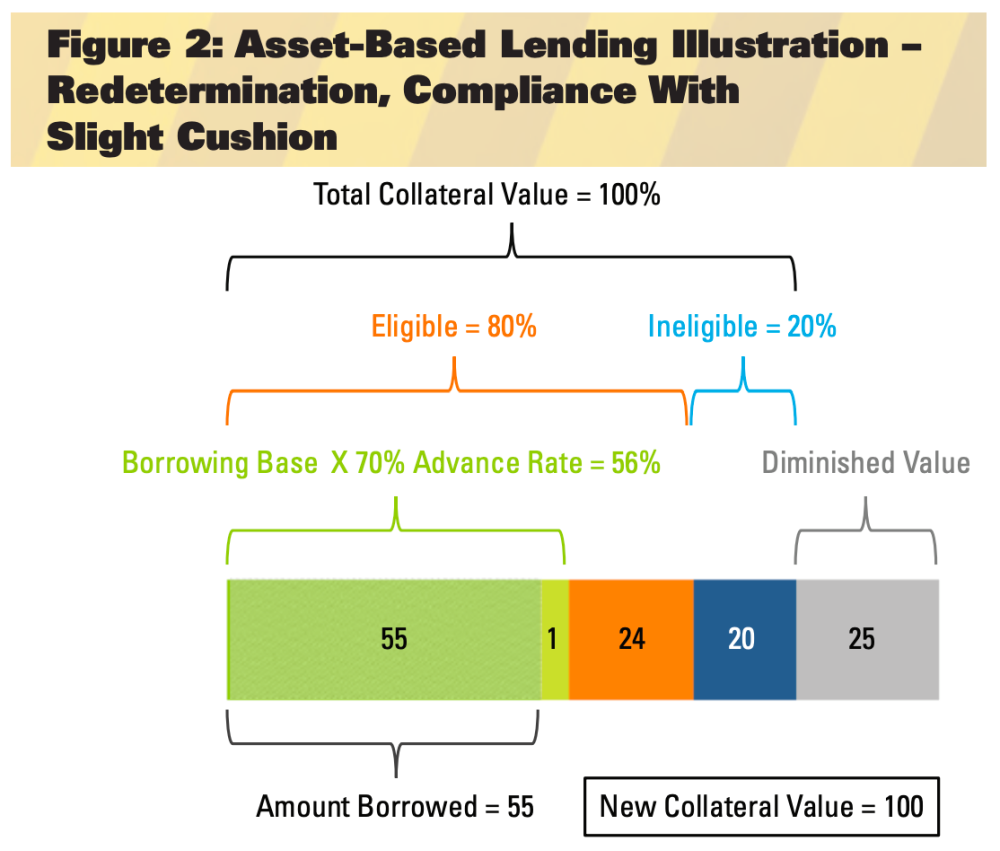

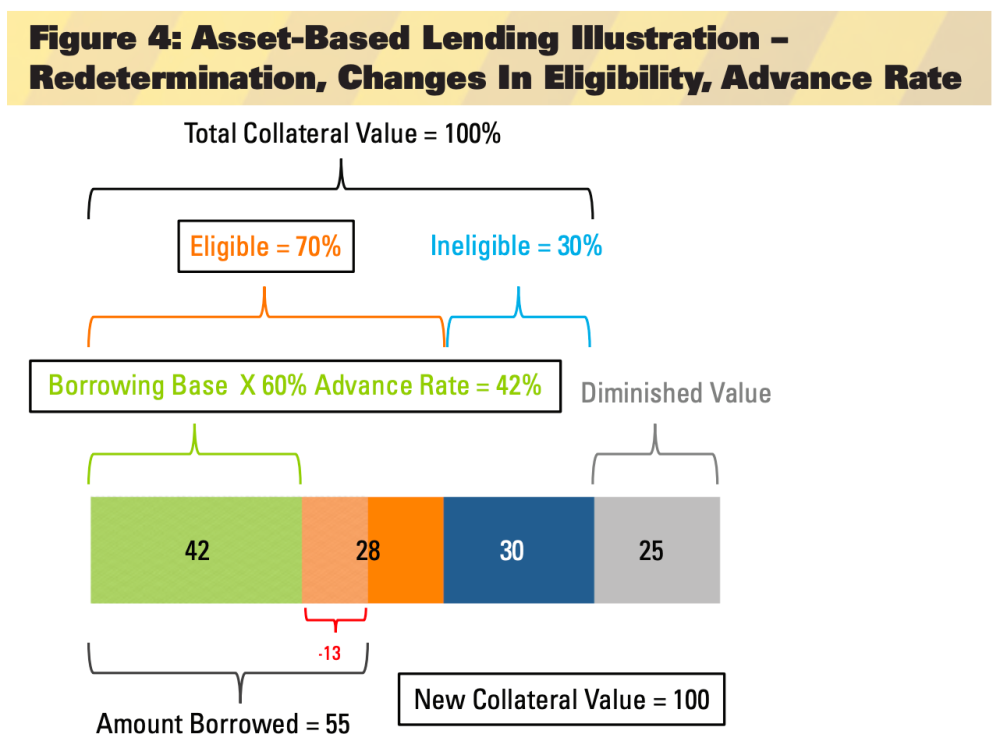

Figures 1 to 4 provide an illustration of this redetermination, as well as other issues that can arise from falling oil prices and declining asset values.

In Figure 1, the base case begins with $125 million of initial total collateral value of which the bank determines that 80% is eligible. The bank proposes to advance up to 70% the value of eligible collateral. Thus, $100 million of the collateral is eligible, and the maximum available loan is $70 million. In this scenario, since the borrower only borrowed $55 million, there exists a comfortable $15 million cushion of excess availability. However, presuming that oil prices collapse, the total collateral value subsequently becomes reduced to $100 million of which 80% is eligible with a 70% advance rate under the predetermined formula. Thus, eligible collateral has now decreased from $100 million to $80 million, and the maximum available loan has reduced further to $56 million. Since the loan amount remains $55 million, the excess availability cushion has shrunk from $15 million to only $1 million. This cushion was meant to absorb unexpected shocks, such as fluctuations in energy commodity prices, by shrinking the borrowing base in proportion to declines in collateral value. In this example, the formula worked since the borrower remained in compliance despite a 20% decrease in total collateral value.

An additional complication, though, is that a sudden drop of 20% of the total collateral value may alarm lenders. A nervous lender may overreact to sharp declines in collateral values across an industry and feel motivated to restrict credit exposure to that sector. Such overreactions may create deficiencies where there were none before, leading to preventable defaults.

In Figure 3, the lender responded to the sudden decline in collateral value by subjectively increasing the calculation of ineligible collateral to 30% of the total collateral value, causing eligible collateral to decrease from $100 million to $70 million (rather than $80 million) and the maximum available loan to be reduced from $70 million to $49 million (rather than $56 million). As a result of this one discretionary change, the borrower suffers a $6 million deficiency rather than having a $1 million cushion.

Lenders can further restrict borrowers by decreasing the advance rate in tandem with collateral value declines. In the figure above, the lender decreased the advance rate to 60% in addition to increasing the calculation of ineligible collateral to 30% of the total collateral value. Accordingly, eligible collateral decreased from $100 million to $70 million (rather than $80 million), and the maximum available loan was reduced from $70 million to $42 million (rather than $56 million). As a result of this double whammy, the borrower suffers a $13 million deficiency rather than having a $1 million cushion.

These examples illustrate how reserve-based loans give lenders the power to deepen the distress for troubled upstream E&P borrowers to overcompensate for sudden drops in energy commodity prices.

Striking a balance for energy loans

Because lenders possess some discretion with borrowing base calculations, they may gain substantial negotiating leverage over such borrowers. During healthy periods for the energy sector, a borrower can usually find alternative lenders to escape an overbearing one. However, during troubled periods, alternatives may not exist. Without alternatives, the existing lender may attempt to coerce the borrower into strategic and operational changes in lieu of curing a borrowing base deficiency, which the lender used its discretion to create in the first place. Lender liability is designed to deter a lender from abusing its negotiating leverage to usurp the judgment of the borrower’s officers and directors.

In fall 2020, approximately 65% of respondents to the Haynes and Boone Borrowing Base Redeterminations Survey said they believed borrowing bases would decrease by 10% or more. Indeed, according to a late-June S&P Global survey of 34 speculative-grade E&P companies, the average borrowing base redetermination was lowered by 23%.

Per the loan agreements for most asset-based loans, the lender has the right to take control of the borrower’s cash if the borrowing base declines to a level below the loan balance. Specifically, most asset-based loans include a deposit account control agreement, which gives lenders control over deposit accounts should a default arise.

Excessive restrictions on liquidity, however, could compel borrowers to act in desperation— drastically cutting payroll, defaulting with vendors—and they may ultimately lose customers because of a hampered ability to fulfill orders. As a result, the lenders may inadvertently impair the value of their collateral, as well as alarm their other borrowers.

Typically, extreme financial distress reduces the ability of the company to collect receivables from its customers on a timely and full basis. Also, vendors may restrict the availability of critical goods and services if they fear that their outstanding invoices will never be paid.

Further, key employees tend to abandon a sinking ship.

Overall, keeping the business as a going concern is often the best way for lenders to maximize their recoveries. Accordingly, from a lender’s perspective, engineering a discrete liquidation is often preferable to forcing an actual liquidation, although lenders should be cautious of adverse consequences for other stakeholders. Notably, harm to other creditors is part of the three-part test for equitable subordination.

When confronted with the harsh reality that customary remedies, such as foreclosing on collateral or sweeping cash accounts, will not maximize their recoveries, a lender usually realizes that it must continue funding losses for a business that may be in a death spiral. As J. Paul Getty, named the richest living American in 1957 by Fortune magazine, explained, “If you owe the bank $100, that’s your problem. If you owe the bank $100 million, that’s the bank’s problem.”

An aggressive lender risks that the borrower will ultimately declare bankruptcy to gain legal protection from its creditors, including the lender. Bankruptcy, however, may not advance the lender’s objective. The costs of administering a bankruptcy case, such as paying for lawyers, trustees, creditors’ committees and other administrative expenses, may diminish the value of the lender’s collateral even further. In some circumstances, the court may approve post-bankruptcy financing with priority ahead of the lender’s secured loan.

Furthermore, the bankruptcy process may prolong an inevitable sale of some or all of the borrower’s assets. Finally, the breathing room provided by the bankruptcy process may allow the borrower to litigate lender liability as a way to improve recoveries for unsecured creditors and delay action by the lender.

The risks and uncertainty involved in bankruptcy often cause lenders to look for out-ofcourt remedies to protect their collateral via loan amendments, forbearance agreements and standstill agreements. These remedies, however, often come with strings attached for the borrower, such as onerous requirements to reduce overhead costs, put the company up for sale, provide more frequent financial reporting, waive potential claims against the lender and other lender-friendly terms and conditions.

When evaluating a troubled borrower, the lender faces the challenge of providing enough cash for borrowers to recover while limiting business activity that poses risks to the lender’s collateral. This balancing act must be done while maintaining an arm’s length relationship. If overreaching causes the lender to cross the line from passive to active investor, the lender may trigger lender liability.

Breach of fiduciary duty

Mitigating strategy: Transparent communication with borrowers.

When a lender begins to pursue its remedies, the borrower may react unexpectedly. With the unfair benefit of hindsight, a court may determine that the lender exercised undue influence over the borrower by pursuing a specific remedy. To avoid surprises, and subsequent liability claims, lenders should create open and transparent lines of communication with borrowers. Ideally, communications should be documented, so consider asking questions via email rather than over the phone. Receiving frequent financial reporting from distressed or defaulted borrowers is also highly recommended. However, distracting executives from managing their day-to-day operations is generally counterproductive.

The need for communication and continuous financial reporting is illustrated in the New York Supreme Court case U.S. Bank N.A. v. DCCA. In the case, the lender refused to provide additional funding to defaulted borrower Doral Arrowwood Hotel and Conference Center. Without that liquidity, the company announced mass layoffs on Christmas Eve, effective on Jan. 12, 2020. The court determined that the lenders knew that their withholding funding would force Doral Arrowwood to close and that employees would not get the 90-day notice of termination required under the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) Act. The bank was held liable for the cost to employees for Doral Arrowwood’s failure to provide 90 days prior written notice of mass layoffs. The situation may have been avoided had the bank been aware of the borrower’s payroll status. Given energy companies’ reliance on banks for liquidity, it is easy to see how a similar scenario could play out in the oil patch.

If the borrower-lender relationship has soured, making meetings contentious, it might be the right time to hire a third party with experience in creating open lines of communication between borrowers and lenders. A restructuring advisor, turnaround consultant or independent director can work with troubled borrowers to restore the lenders’ credibility.

Tortious interference

Mitigating strategy: Avoid any perceived or actual advisory role with the borrower.

In an effort to safeguard collateral, lenders may be tempted to provide advice to troubled borrowers regarding working capital management, overhead expenses, employee retention, marketing initiatives, agreements with customers and vendors, maintenance capex, potential asset sales and other topics related to day-to-day operations. However, history is replete with instances of lenders being found liable for providing advice to borrowers that resulted in damage to the borrower’s other stakeholders.

Additionally, lenders should beware of relationships with borrowers that are atypical, i.e., what courts have deemed “special relationships,” that can impose certain fiduciary duties on the lender if the lender is ruled to have exercised extensive control.

Avoiding advisory roles is of particular importance under the Paycheck Protection Program, whereby borrowers are only eligible for loan forgiveness if they meet certain criteria. Lenders should take particular caution that they do not advise borrowers in ways that could seem to manipulate borrower’s eligibility for loan forgiveness.

“Lender liability is designed to deter a lender from abusing its negotiating leverage to usurp the judgment of the borrower’s officers and directors.”

Because lenders provide financing to many borrowers, they may have a good idea of typical industry practices. Therefore, it can be tempting to offer proposed “benchmarks” or “norms.” Lenders should make it clear to borrowers, in writing, that no advisory relationship exists between them. If a lender thinks that a troubled borrower would benefit from an outside perspective, then the lender should encourage the borrower to hire a restructuring advisor, turnaround consultant or independent director to maintain the arm’s length relationship between the lender and the borrower. While the lender can approve of the person or firm being hired, the lender, as a passive investor, should not be the one making the final decision.

Duty of good faith and fair dealing

Mitigating strategy: Avoid providing assurances to the borrower, and communicate clearly and consistently the lender’s obligations.

Given the federal “perks” provided to lenders that administer coronavirus relief loans, there may be an expectation from the courts that the lenders work with borrowers, rather than simply “canceling” the loan.” For example, lenders under the Main Street Lending Program only retain 5% participation in any Main Street Loan, and federal banking agencies modified capital rules in favor of lenders participating in the PPP program. Even prior to the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act, there have been several cases where lenders’ failure to work with borrowers, imposing steep penalties that borderline excessive control, has resulted in imposing additional liability. In K.M.C. Co. v. Irving Trust Co, K.M.C. asserted that Irving’s refusal to fund without prior notice breached a duty of good faith implied in the agreement and led to the collapse of the company. Irving paid K.M.C. $7.5 million for its failure to act in good faith.

Irrespective of court expectations, it is often in a lender’s best interests to negotiate with its troubled borrowers, providing them with amendments or forbearance agreements. In the case of energy asset-based lending, lenders would likely encounter severely depressed prices were they to foreclose and attempt to sell energy assets while values are low, like during the COVID-19 pandemic. Negotiations can maximize recovery. Regardless of the course of action, it is important that lenders communicate clearly about the current remedies sought.

Breach of contract

Mitigating strategy: Establish a fireproof loan application process.

Because lenders and borrowers have a contractual relationship, lenders could be held liable for breaching oral, implied and written contracts. Despite the enormous volume of applications lenders have received pursuant to the CARES Act, lenders still have a duty to process loan applications with reasonable care. If a bank’s failure to process a borrower’s loan application in a timely manner is to the borrower’s detriment, the bank could be liable. Clearly, lenders should document the loan application process for both internal and external use to manage timing expectations among borrowers and prevent internal processing errors.

Fraud involving lender liability

Mitigating strategy: Communicate with caution about providing any guarantees of funds, amendments or forbearance when these cannot be assured.

When negotiating remedies, do not make promises you cannot keep. Lenders have been found liable for threatening borrowers with no ability or intention to follow through with those threats. Make it clear that you are in the midst of negotiations and that remedies have not been finalized.

Require borrowers to provide written confirmation that they recognize that their loan is in default and that they have agreed to engage in negotiations. A neutral third party can aid in quickening negotiations, and restructuring advisors are experienced in negotiating with all stakeholder groups. In some cases, advisors may provide borrowers with refinancing opportunities to move troubled loans out of lender portfolios.

The value of a third-party voice

Restructuring advisors are seasoned at dealing with distressed firms and can help you and your borrowers navigate an out-of-court workout or bankruptcy proceeding. Hiring a restructuring advisor can help mitigate lender liability risk by maintaining an arm’s length relationship as well as:

- Improve reporting accuracy and transparency;

- Evaluate borrower liquidity and provide cost recommendations that do not violate the arm’s length relationship;

- Provide paths to open, thorough, documented communication throughout the application and modification process; and

- Equip borrowers with effective benchmarking tools.

Bringing in an objective, third-party restructuring advisor to guide all players’ next steps can help mitigate lender liability risk while working toward maximized outcomes for all stakeholders. During a distressed situation, the lender will likely resent “leakage” of cash going to fund interest payments on unsecured debt, bonuses to key employees, timely payments to vendors, management fees to sponsors, marketing initiatives, routine maintenance of equipment and professional fees to advisors or consultants, even though such expenditures may be needed to maximize valuation of the enterprise.

While the lender’s desire to protect the value of its collateral may diverge from the interests of unsecured creditors and equityholders in rehabilitating the value of the business, lenders should be wary of overstepping their bounds.

Jeff Anapolsky has more than 20 years of leadership experience in finance, law and operations, including more than 40 out-of-court workouts and bankruptcy reorganizations. As an industry generalist and functional expert, he has created credible forecasts, raised private capital, resolved multiparty disputes, determined complex valuation, managed transaction closings and delivered effective presentations for a variety of special situations.

Recommended Reading

Santos’ Pikka Phase 1 in Alaska to Deliver First Oil by 2026

2024-04-18 - Australia's Santos expects first oil to flow from the 80,000 bbl/d Pikka Phase 1 project in Alaska by 2026, diversifying Santos' portfolio and reducing geographic concentration risk.

Iraq to Seek Bids for Oil, Gas Contracts April 27

2024-04-18 - Iraq will auction 30 new oil and gas projects in two licensing rounds distributed across the country.

Vår Energi Hits Oil with Ringhorne North

2024-04-17 - Vår Energi’s North Sea discovery de-risks drilling prospects in the area and could be tied back to Balder area infrastructure.

Tethys Oil Releases March Production Results

2024-04-17 - Tethys Oil said the official selling price of its Oman Export Blend oil was $78.75/bbl.

Exxon Mobil Guyana Awards Two Contracts for its Whiptail Project

2024-04-16 - Exxon Mobil Guyana awarded Strohm and TechnipFMC with contracts for its Whiptail Project located offshore in Guyana’s Stabroek Block.