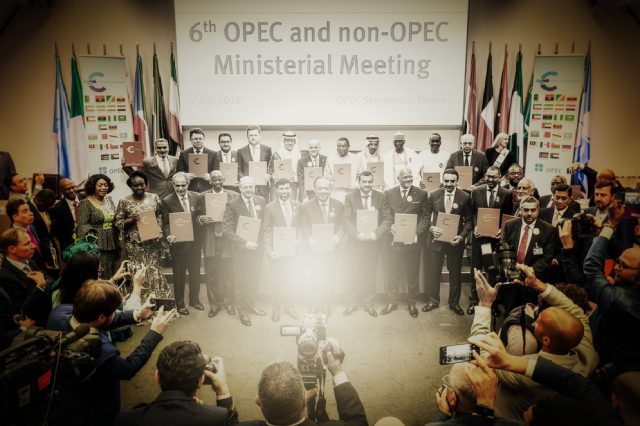

OPEC and non-OPEC ministerial meeting in Vienna in July 2019. (Source: OPEC)

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the September 2020 issue of Oil and Gas Investor magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

September 1960 will be remembered by baseball fans, political junkies and oil industry watchdogs. Here’s why.

That month, Pittsburgh baseball fans were on fire. Their beloved Pirates had just clinched the pennant in Milwaukee and, thus, the team was on the way to its first World Series since 1925. Later that October, the players won it all in Game 7 over the New York Yankees, 10 to 9, with a walk-off home run. This has been labeled one of the most exciting Game 7s in baseball history, with the lead changing hands four times.

On Sept. 26, history was made in another, more serious way. Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy faced off in a CBS studio in Chicago for the first-ever televised campaign debate between two presidential contenders. The symbiotic link between politics and television has never been the same since.

On a macroeconomic level, something even more momentous occurred, for on Sept. 14, some large oil producers met in Baghdad to discuss the sorry state of global oil prices. The result? The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries was formed. The five founding members were Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Venezuela and Kuwait.

They met to figure out how to offset low oil prices caused by a supply glut—sound familiar? Starting in the mid-1950s, U.S. production had increased just as discoveries in the Middle East enabled those countries to ramp up oil production. The tug of war between the West and the Middle East began.

Sixty years later, is OPEC as relevant today as it was then? As powerful? During the shale boom from 2008 to 2014, it was fashionable to say no. Rising U.S. oil production and exports from our shores were remaking global oil flows, risk, storage fundamentals and prices. Before the pandemic hit, we were exporting about 3 MMbbl/d and producing about 12% of the world’s oil. That’s rookieof-the-year star power.

But in 2019, OPEC collectively produced 42% of the world’s oil, in a league of its own. Saudi Arabia produced about 12% at the height last year, Russia 11%. When adding Iraqi output, these three members of OPEC+ account for more than a third of the world’s oil supply. That’s hall of fame status that cannot be dismissed.

Since 1960, it’s always been too easy to blame OPEC for the industry’s woes whenever oil prices crash—even if it’s because of a supply glut caused by others, or an unprecedented drop-off in demand caused by a virus. It’s also been way too easy to wish OPEC would do something to fix the industry’s troubles—even if that’s really a matter of global economic or geopolitical factors instead.

The only real Band-Aids an individual producer has at hand are to hedge and cut costs. Bring on those swaps, collars and floors. Shut in producing wells and stop drilling. That has been done.

The EIA said that in May during the worst of it, U.S. oil production dropped by 1.9 MMbbl/d or nearly 17%, the largest monthly decline since 1980.

The top 25 public U.S. producers cut production by almost three-quarters of a million barrels a day, according to Rystad Energy. But OPEC has cut even more, some 1.2 MMbbl/d from January 2019. In May 2020 when repercussions from the pandemic and global downturn were severe and more visible, OPEC+ agree to cut by 9.7 MMbbl/d. Oil is hovering around $44/bbl.

But let’s face it—although we can debate the importance of OPEC, it’s clear that we all hang on the organization’s every word, perhaps never more so than this year, a year that will go down in infamy. Negative WTI? Global demand down more than at any time in history? Demand for OPEC oil supply fell to an astonishing 30-year low in April.

At press time, OPEC revised its 2020 energy outlook, saying world oil demand will fall by 9 MMbbl/d this year. It does not see demand in 2021 getting back to what it was in 2019, but it retained its forecast that demand will improve some next year, by 7 MMbbl/d. The International Energy Agency (IEA) reduced estimates for oil demand for almost every quarter through to the end of 2021.

“The energy market is still flashing the same warning signs it has been flashing since March,” wrote Robert Yawger, director of energy futures, Mizuho Securities USA, in August. “The situation has improved some, but the market dynamics are still less than stellar. For starters, the stubborn contango curve continues to rule the WTI price curve. Contango curve implies the market is oversupplied.”

The upshot seems to be that when U.S. producers vow to spend only enough to hold production flat, their place in the game may change. IHS Markit’s Raoul LeBlanc thinks that a grand reset is unfolding, with shale possibly never regaining its former batting average.

Recommended Reading

Asia Spot LNG at 3-month Peak on Steady Demand, Supply Disruption

2024-04-12 - Heating demand in Europe and production disruption at the Freeport LNG terminal in the U.S. pushed up prices, said Samuel Good, head of LNG pricing at commodity pricing agency Argus.

US Natgas Prices Hit 5-week High on Rising Feedgas to Freeport LNG, Output Drop

2024-04-10 - U.S. natural gas futures climbed to a five-week high on April 10 on an increase in feedgas to the Freeport LNG export plant and a drop in output as pipeline maintenance trapped gas in Texas.

US NatGas Futures Hit Over 2-week Low on Lower Demand View

2024-04-15 - U.S. natural gas futures fell about 2% to a more than two-week low on April 15, weighed down by lower demand forecasts for this week than previously expected.

Report: Freeport LNG Hits Sixth Day of Dwindling Gas Consumption

2024-04-17 - With Freeport LNG operating at a fraction of its full capacity, natural gas futures have fallen following a short rally the week before.

API Gulf Coast Head Touts Global Emissions Benefits of US LNG

2024-04-01 - The U.S. and Louisiana have the ability to change global emissions through the export of LNG, although new applications have been frozen by the Biden administration.