Despite the deal to gain Sen. Joe Manchin’s (D-W.Va) vote for the Inflation Reduction Act, passage of Manchin’s permitting reform legislation in September is not a slam dunk. And if the bill does pass, it may do little to accelerate the pace of infrastructure projects, legal experts told Hart Energy.

“I would anticipate, certainly, a change in perspective on the side of the federal regulator, but that does not mean that the permits for any particular project are a foregone conclusion or a project development is a fait accompli,” said Cale Jaffe, law professor at the University of Virginia. “There still are other stakeholders that are not parties to that agreement and I think you’ve seen that from a lot of the nonprofits who have already said they still intend to fight oil and gas infrastructure projects that they’ve been opposing.”

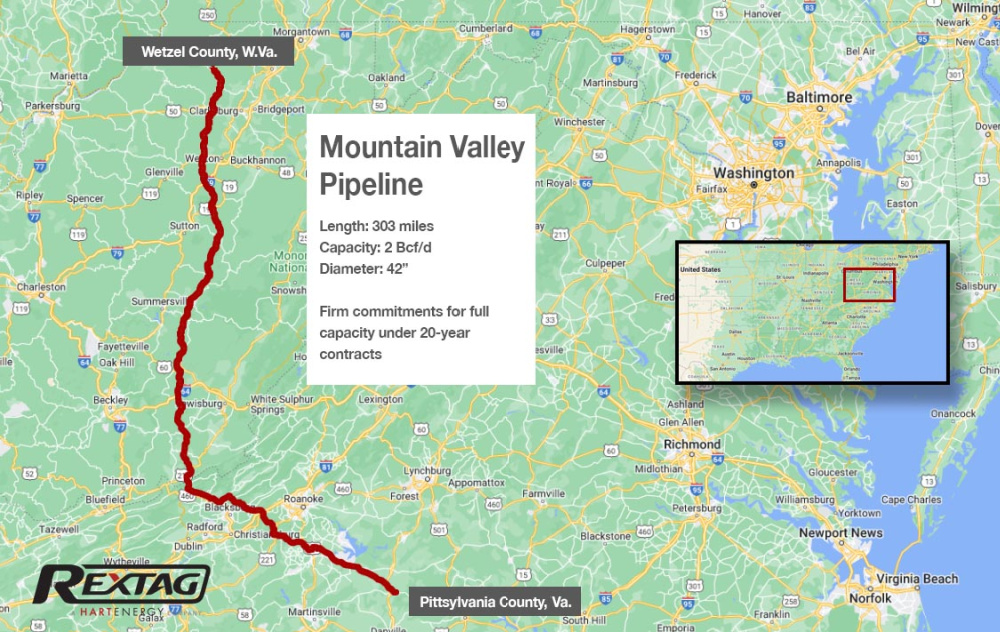

The deal between Manchin and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) promised a vote on the permitting reform bill before the end of the fiscal year on Sept. 30. Among its provisions is a requirement for “relevant agencies to take all necessary actions permit the construction and operation of the Mountain Valley Pipeline.” It also would move all future litigation of the project to the jurisdiction of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit from the Fourth Circuit.

“I cannot think of any other legislative precedent for moving an active controversy from one federal circuit to a different federal circuit.”—Cale Jaffe, University of Virginia

No legislation has been submitted, but Manchin has said it will be attached to a spending bill that must pass to avoid a government shutdown. A single-page rundown of provisions that has circulated around Capitol Hill has already aroused opposition. Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.) told The American Prospect that progressives “sure as hell don’t owe Joe Manchin anything now. He and his fossil fuel donors already got far too much in the IRA.” On the Republican side, Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) said, “I will not vote for a continuing resolution that is part of a political payback scheme.”

Time frames

According to the rundown, the bill would set maximum timelines for permitting reviews under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). They would be two years for major projects and one year for lower-impact projects.

Speeding up the permitting process drew support from Equitrans Midstream Corp., the lead stakeholder in the consortium building the long-delayed Mountain Valley Pipeline.

“The proposed permitting reform legislation addresses issues that have presented costly, time-consuming delays in the construction of energy infrastructure projects and supports Americans’ demands to execute a timely transition to clean energy, while at the same time ensuring energy reliability and affordability,” Natalie A. Cox, spokeswoman for Equitrans Midstream, told Hart Energy. “By providing a timely and certain permitting process, the proposed legislation would benefit all energy infrastructure projects, which is just as important for renewable energy infrastructure projects as it is for oil and gas.”

David Adelman, professor of law at the University of Texas at Austin, agrees that resolving permitting issues is critical to managing the scale of development needed for the energy transition.

“We are not prepared for it,” he told Hart Energy. “This is a pressing issue and it would be wonderful if we could develop permitting reform in a thoughtful, constructive way.”

Strict time frames, however, may not be the way to go.

“Having an arbitrary time limit, I think, probably will be useless,” Adelman said. “In a lot of cases, it won’t matter; it can be done in that time period. But so much of it is going to turn on how you measure that two-year period.”

If the time frame is not well defined, federal regulators might be tempted to delay environmental reviews until later in the evolution of the project, he said. This could happen if they believe the project will be delayed for other reasons or change significantly.

“Basically, what the agencies could do is game the system so that even if they’re initiating some consultation and some work, they haven’t formally started the time for preparing an EA (environmental assessment) or the time preparing an EIS (environmental impact study), and I think it would be really hard to monitor that,” Adelman said.

He also disagrees with the logic that all delays are associated with the actual process of undertaking the analysis and writing up the EA or the EIS. Often, the key factor is resource limits that hold up projects, Adelman said, referring to a federal agency’s shortage of people or budget.

Change of venue

Perhaps the most unusual aspect of the agreement between Manchin and Schumer is moving jurisdiction of cases involving the Mountain Valley Pipeline to the more conservative D.C. Circuit from the Fourth Circuit, where groups opposing the natural gas project have had some success.

“It’s going to be a more favorable forum for the federal government,” Adelman said. “It’s flagrant forum shopping.”

“It’s certainly novel,” Jaffe said. “I cannot think of any other legislative precedent for moving an active controversy from one federal circuit to a different federal circuit.”

“This is a pressing issue and it would be wonderful if we could develop permitting reform in a thoughtful, constructive way.”—David Adelman, University of Texas at Austin

There is, however, precedent for designating the D.C. Circuit as the forum for challenges. Under the Natural Gas Act, an appeal to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission on a natural gas permit decision goes directly to the D.C. Circuit, he said.

“It’s not as if D.C. Circuit hasn’t weighed in on some of these issues,” Jaffe said. “Litigants will find D.C. Circuit decisions that are favorable to the oil and gas industry and they can find D.C. Circuit precedents that are favorable to community opponents of that infrastructure. And there are cases that you could cite on both sides.”

Jaffe also questioned a provision to address excessive litigation delays.

“I don’t have the sense that the cases on the [Mountain Valley] Pipeline have languished, frankly,” he said. “There have been some wins and losses on all sides and subsequent appeals that, of course, take some time but I can’t think of a case where it was briefed and argued and then just sat unresolved for a year or more.”

And victories in court don’t necessarily result in a project’s success. Dominion Energy and Duke Energy prevailed in the Supreme Court in 2020 to gain permitting for the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Less than three weeks later, they canceled the project.

The political climate in Washington might pose the biggest challenge to the bill. Acrimony over the process of passing the Inflation Reduction Act could, strangely, put some Democrats in opposition to a measure that could accelerate construction of infrastructure for renewable fuels. Some Republicans might find themselves refusing to vote on legislation that would benefit fossil fuel interests.

“It seems like it would have to be bipartisan,” Adelman said. “That is going to be challenging to put it together so that you can attract some Republicans but not make it overly Draconian. Threading that needle strikes me as something that will be hard.”

Recommended Reading

EQT Sees Clear Path to $5B in Potential Divestments

2024-04-24 - EQT Corp. executives said that an April deal with Equinor has been a catalyst for talks with potential buyers.

Matador Hoards Dry Powder for Potential M&A, Adds Delaware Acreage

2024-04-24 - Delaware-focused E&P Matador Resources is growing oil production, expanding midstream capacity, keeping debt low and hunting for M&A opportunities.

TotalEnergies, Vanguard Renewables Form RNG JV in US

2024-04-24 - Total Energies and Vanguard Renewable’s equally owned joint venture initially aims to advance 10 RNG projects into construction during the next 12 months.

Ithaca Energy to Buy Eni's UK Assets in $938MM North Sea Deal

2024-04-23 - Eni, one of Italy's biggest energy companies, will transfer its U.K. business in exchange for 38.5% of Ithaca's share capital, while the existing Ithaca Energy shareholders will own the remaining 61.5% of the combined group.

EIG’s MidOcean Closes Purchase of 20% Stake in Peru LNG

2024-04-23 - MidOcean Energy’s deal for SK Earthon’s Peru LNG follows a March deal to purchase Tokyo Gas’ LNG interests in Australia.