New England’s grid operator says a prolonged cold period could force it to ration electricity supply this winter. (Source: Shutterstock.com)

A European-style winter energy crunch is looming over New England in the Northeast U.S., even as American natural gas producers export record volumes and a wave of fuel heads across the Atlantic.

Utility bosses in the region have called for emergency assistance from Washington to pre-empt a crisis, while lashing out at a century-old law that has cut New England off from some of America’s prolific shale output and left it more dependent on expensive imports.

On Nov. 18, a vessel laden with LNG will land in Massachusetts—but the federal law preventing foreign vessels sailing between U.S. ports means the gas will come from Trinidad, not the U.S. export plants along the Gulf of Mexico that are shipping record amounts of fuel abroad.

“You would think that charity would begin at home . . . that American fuel would go to American ports,” Joe Nolan, CEO of Eversource Energy, one of New England’s biggest utilities, said in an interview. “We’re going to have to compete just like everybody else—in the global market.”

The New England regional grid operator has said it will be able to cope under normal weather conditions this winter, but warned that a prolonged period of particularly cold temperatures could force it to ration electricity supply, potentially through rolling blackouts.

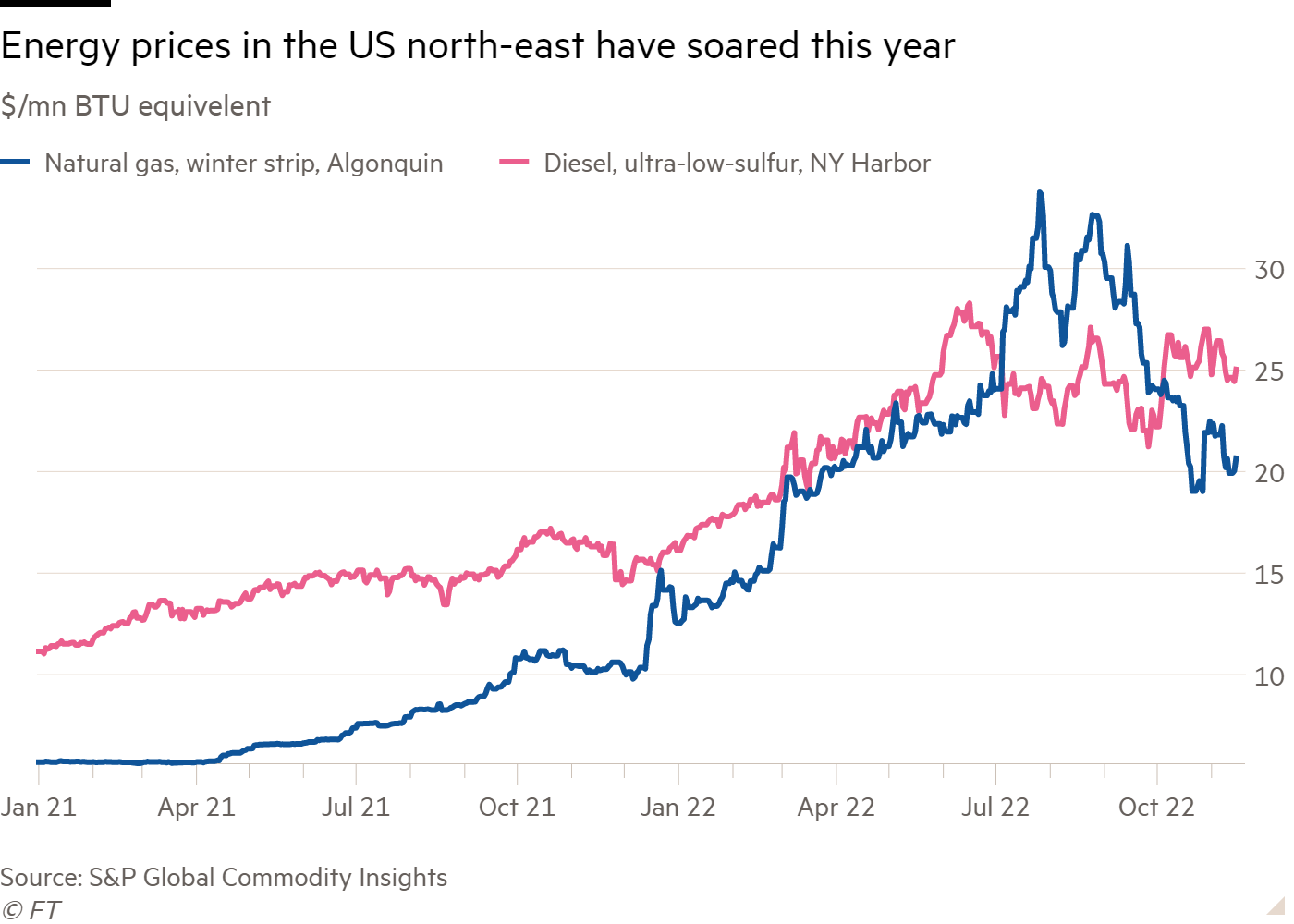

Prices for gas to be delivered in Boston this winter have soared to almost $30/MMBtu on the Intercontinental Exchange, comparable to current prices in Europe, where utilities are scrambling to find international supplies to replace Russian energy.

Gas elsewhere in the U.S. for the same months is trading at about a quarter of that level. Spot prices even plunged below zero in western Texas in recent weeks, as production has climbed to new highs.

RELATED

West Texas Gas Price Falls Below Zero from Pipeline Outages

Plans to pipe more gas to New England from huge shale deposits in nearby Appalachia were scrapped in recent years, while the 1920 Jones Act prevents foreign vessels—such as LNG carriers—from delivering gas superchilled on the Gulf to customers in the Northeast.

As Gulf terminals export record volumes of gas, Elizabeth Warren, the Democratic senator from Massachusetts, this year urged the administration of Joe Biden to curb LNG exports “to keep prices low for American consumers.”

The vessel arriving from Trinidad at the Everett LNG terminal near Boston will be the 11th to land in the region this year, up from nine last year, according to Kpler, a tanker tracker. The price is likely to be close to European levels, said analysts. The terminal owner, Constellation Energy, said the U.S. Coast Guard prohibited it from publicly disclosing information about cargoes arriving into the terminal.

Despite the imports, utilities responsible for electricity transmission in the region, including Avangrid and National Grid, have warned of New England’s “tenuous reliability position” as temperatures drop.

“On the precipice of the 2022-2023 winter period, New England is facing retail energy supply prices that are approximately twice what they were last winter and, perhaps more concerning, a dangerous fuel security situation should the region experience prolonged cold weather or an unplanned disruption to fuel supplies,” they wrote in a submission to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) last week.

The region has been in the vanguard of efforts to decarbonize U.S. energy supply and build up new renewable power generation capacity, and a nascent offshore wind industry is starting to take root.

But those developments will take time and analysts say the retirement of nuclear capacity, the blocking of new power transmission lines from Canada and gas pipelines from western Pennsylvania’s shale gas fields, as well as overly rosy assumptions about cheap foreign supplies, have left New England exposed.

“You sleep in the bed you make,” said Jen Snyder, senior adviser at energy consultancy Validere. “There were decisions along the way that were a little optimistic about oil and LNG prices and about how quickly . . . wind and solar could serve a bigger and more consistent share of the power market.”

“We are importing LNG—but we are also importing European prices,” Snyder added.

The dim outlook for natural gas supplies is mirrored in the market for liquid fuels known as distillates, including diesel and the heating oil that is used as a fuel in many New England households.

The Energy Information Administration warned on Nov. 17 that households using heating oil—about a third of homes in the Northeast, versus 4% nationally—would pay 45% more for their fuel this winter than last due to a tight market. Stocks of the fuel in the Northeast have fallen by nearly half over the past year.

An assessment by the non-profit North American Electric Reliability Corp. (NERC) last week found that without “considerable effort” to replenish stocks of oil and LNG, there were concerns as to “whether there will be sufficient energy available to satisfy electricity demand during an extended cold spell.”

A Department of Energy spokesperson said the administration was engaging with companies on ways to increase inventories and would “continue to closely monitor the situation, work with state and industry partners, and is ready to support as appropriate.”

Nolan of Eversource Energy recently wrote to Biden calling for an emergency federal response to pre-empt a crisis, including the release of supplies from a federal fuel stockpile and a waiver of the Jones Act, saying the Northeast’s reliance on foreign supplies could worsen a global supply crisis too.

“Additionally, increasing reliance on foreign-sourced natural gas poses a particular national security threat at this time given the war in Ukraine,” he said.

Recommended Reading

Canadian Natural Resources Boosting Production in Oil Sands

2024-03-04 - Canadian Natural Resources will increase its quarterly dividend following record production volumes in the quarter.

Par Pacific Asset-based Revolving Credit Bumped Up by 55%

2024-03-25 - The amendment increases Par Pacific Holdings’ existing asset-based revolving credit facility to $1.4 billion from $900 million.

NGL Growth Leads Enterprise Product Partners to Strong Fourth Quarter

2024-02-02 - Enterprise Product Partners executives are still waiting to receive final federal approval to go ahead with the company’s Sea Port Terminal Project.

Enbridge Advances Expansion of Permian’s Gray Oak Pipeline

2024-02-13 - In its fourth-quarter earnings call, Enbridge also said the Mainline pipeline system tolling agreement is awaiting regulatory approval from a Canadian regulatory agency.

E&P Earnings Season Proves Up Stronger Efficiencies, Profits

2024-04-04 - The 2024 outlook for E&Ps largely surprises to the upside with conservative budgets and steady volumes.