As the first American woman to summit and descend Mount Everest without supplemental oxygen, world-class mountain climber Melissa Arnot has learned a lot from her journeys in nature—knowledge that applies to all walks of life, she says. (Courtesy of Melissa Arnot)

By any measure, Melissa Arnot is an achiever. A working mountain guide since 2004, she has logged more than 100 climbs on Mount Rainier in Washington and has guided ascents of Aconcagua as well as the Colombian Andes, volcanoes in Ecuador, Kilimanjaro and multiple peaks in Nepal.

Arnot is the first American woman to successfully summit and descend Mount Everest without supplemental oxygen and has climbed the world’s highest peak six times. If that isn’t impressive enough, she also completed the Fifty Peaks Challenge, summiting the highest point in each of the 50 states, an achievement that, as of 2018, only 272 other people had accomplished. In 2016, Arnot set a world record with climbing partner Maddie Miller, completing all 50 ascents in 41 days, 16 hours and 10 minutes, a full 24 hours faster than the previous world record holder.

Looking at the long list of “firsts” and achievements, it is easy to assume Arnot is simply extraordinarily gifted—and possibly very lucky. But that would be an oversimplification.

Every milestone was the hard-won result of training, persistence, dedication and hard work. And every “first” was preceded by missteps and failures.

But for Arnot, the “failures” on her path have been more like mile markers on her journey to achievement.

“Success is achieving something and asking, ‘Now what?’ but failure contains the possibilities,” she said. “It tells you this is where you are and challenges you to figure out what you need to do to get beyond that point. Failures are where all the learning and all the progress exist.”

The path to the summit

It might be surprising to know that Arnot did not begin climbing until she visited Glacier National Park in Montana with a friend when she was 19 years old.

“I went climbing there, and everything clicked,” she said. “In beautiful places like that, every step you take opens up new possibilities. You imagine all the other places you can go. I knew on that first climb that if I got better and more skilled, I would have endless opportunities to explore, and I reoriented my life toward learning everything I could about climbing.”

Hearing her talk about how she found her passion inspires many, but the fact that she immediately recognized her calling can be a bit intimidating for those who are still searching for theirs.

According to Arnot, it is not unusual to be unsure about the path ahead, and it is OK to leverage someone else’s passion.

“Let somebody else’s passion be your inspiration for finding your own,” she said, but cautioned, “Don’t make their passion your passion. Follow them. See how they live and how they clarify the voice of that passion and how it directs their actions.”

In short, “Follow your values,” she said, and take the time to recognize the difference between values and validation.

That can be difficult, but Arnot suggested one way to make that distinction is to ask some basic questions. “What things do you do when you’re totally alone? What are you doing for yourself simply because you just feel good about doing it?”

The answers provide clarity and purpose.

“I feel better succeeding for myself rather than achieving a goal just to prove someone wrong,” Arnot said. “There are always going to be people saying negative things about you. Living your life and accomplishing things just to prove them wrong is a sort of ‘chasing your tail’ way to live.”

And running in circles will never lead upward.

The value of being present

Distilling personal experiences to find your purpose takes focus, Arnot said, and sometimes finding that focus can be challenging.

For Arnot, who is extremely active and is happiest when she is under pressure with a full schedule of commitments, the mountain dictates a slower pace, forcing her to slow down because, as she put it, “The consequences of inattentiveness can be fatal.”

But truly being in the present is not as easy as it sounds.

“We think of being present as not doing anything, as just being,” Arnot said, “but there is so much ‘doing’ in being present.”

On a mountain expedition, she said, “I have to be completely present. That is nonnegotiable. That is what nature teaches me. I need to have the clarity of what’s in front of me while maintaining a sense of the big picture.” There is no room for any distractions.

“Being present is challenging any time you’re doing something really hard that has consequences, and that is different for everyone. We all face challenges on a microlevel every day of our lives, and we push through the difficulty. You go past the discomfort and that gives you an incredible sense of knowing what you can handle.”

From the mountains to the mundane

The mountains are a palpable, experiential way to meet personal challenges for mountaineers like Arnot, but for her, that experience is not confined to climbing. “I apply that to the rest of my life all the time,” she said. “I know I can get through discomfort, and I know what that feeling is on the other side of the discomfort. It is the feeling of growth. It is the knowledge of what I’m capable of.”

The way a person confronts discomfort is critical to achieving progress, Arnot said. “If you are facing really adverse conditions, you can’t lead your way out of that. You have to listen and be responsive.”

That can be particularly difficult for people who like to have a plan.

“One of the biggest lessons the mountains teach me, especially as a Type-A person who likes to control the things I can, is that there will always be situations where I am not in control,” she said. “Being in an environment you absolutely cannot control teaches you to listen, evaluate and react.”

In day-to-day interactions, being reactionary can be viewed as negative, but as with so many other traditional definitions, Arnot turns this one on its head. “I see it as a positive trait,” she said. “Nature teaches us that systems go out the window in a dynamic environment. You see what’s in front of you, and you react to that, and that plays forward into how we work within the team.”

Reversing the rope

Teamwork is imperative in mountain climbing, but team members do not always fill the same role, Arnot said, noting that the fluidity of roles is vitally important.

“There is tremendous value in holding every space in a team,” she said. “When we climb with a rope, one person typically climbs to the summit and then flips the rope so the person who was on the back of the rope leads the way down. Every person along the rope is a member of the team as a leader and a follower.”

This challenges the traditional team structure of a leader and a top-down hierarchy. “The mountains teach you that you have to lead from all positions,” she explained. “You have to be able to stand in each role and fill it.”

That lesson translates to the workplace.

“The leaders you’ve enjoyed working with are those who have let you lead them as well,” Arnot said.

Recommended Reading

Darbonne: The ESG Sword: BlackRock's Life, Death by ESG

2024-04-17 - BlackRock, the $10 trillion investment manager, is getting heat for too much ESG investing, while shareholders are complaining it’s doing too little.

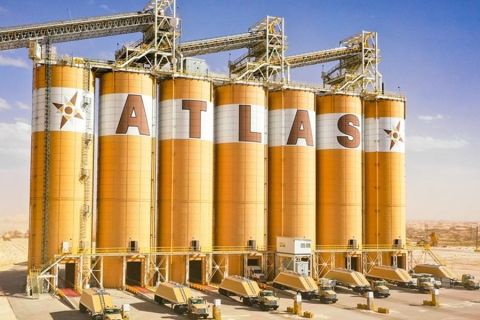

Fire Closes Atlas Energy’s Kermit, Texas Mining Facility

2024-04-15 - Atlas Energy Solutions said no injuries were reported and the closing of the mine would not affect services to the company’s Permian Basin customers.

Coalition Launches Decarbonization Program in Major US Cities, Counties

2024-04-11 - A national coalition will start decarbonization efforts in nine U.S. cities and counties following a federal award of $20 billion “green bank” grants.

Exclusive: Scepter CEO: Methane Emissions Detection Saves on Cost

2024-04-08 - Methane emissions detection saves on cost and "can pay for itself," Scepter CEO Phillip Father says in this Hart Energy exclusive interview.