[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the September 2020 edition of Midstream Business. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

Energy Transfer Partners, as the kids would say, got “2020ed.” The company’s Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) was ordered to shut down in early July by a federal judge who ruled that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers did not conduct an environmental impact statement as required before issuing a permit.

So, three years after DAPL went into operation to transport crude oil from the Bakken Shale to Patoka, Ill., a judge issued his decision based on a rule broken by a third party (the Corps). Three years. Now, friends, you know what it means to be 2020ed.

While that kerfuffle works itself out in court, it’s worth noting that an actual project, the DAPL expansion, could be in doubt. The company planned to double capacity from 570,000 bbl/d to 1.1 MMbbl/d, but the oil price shock and loss of demand cut deeply into Bakken Shale producers’ enthusiasm for the project.

“Honestly, [the DAPL expansion] is not needed,” an anonymous E&P executive whose company committed to space on the expanded pipeline told Reuters. “Would I like to get out? Yes, for sure.”

Those kinds of sentiments convinced Energy Transfer to declare force majeure to compel committed producers to stick with the project and honor their contracts. The federal court decision in early July didn’t help.

“We would assume an expansion would be off the table if DAPL is forced to close, but this is yet another loose end to tie up,” Wells Fargo equity researchers said in a July 8 report. “For now, our estimates continue to assume a DAPL expansion.”

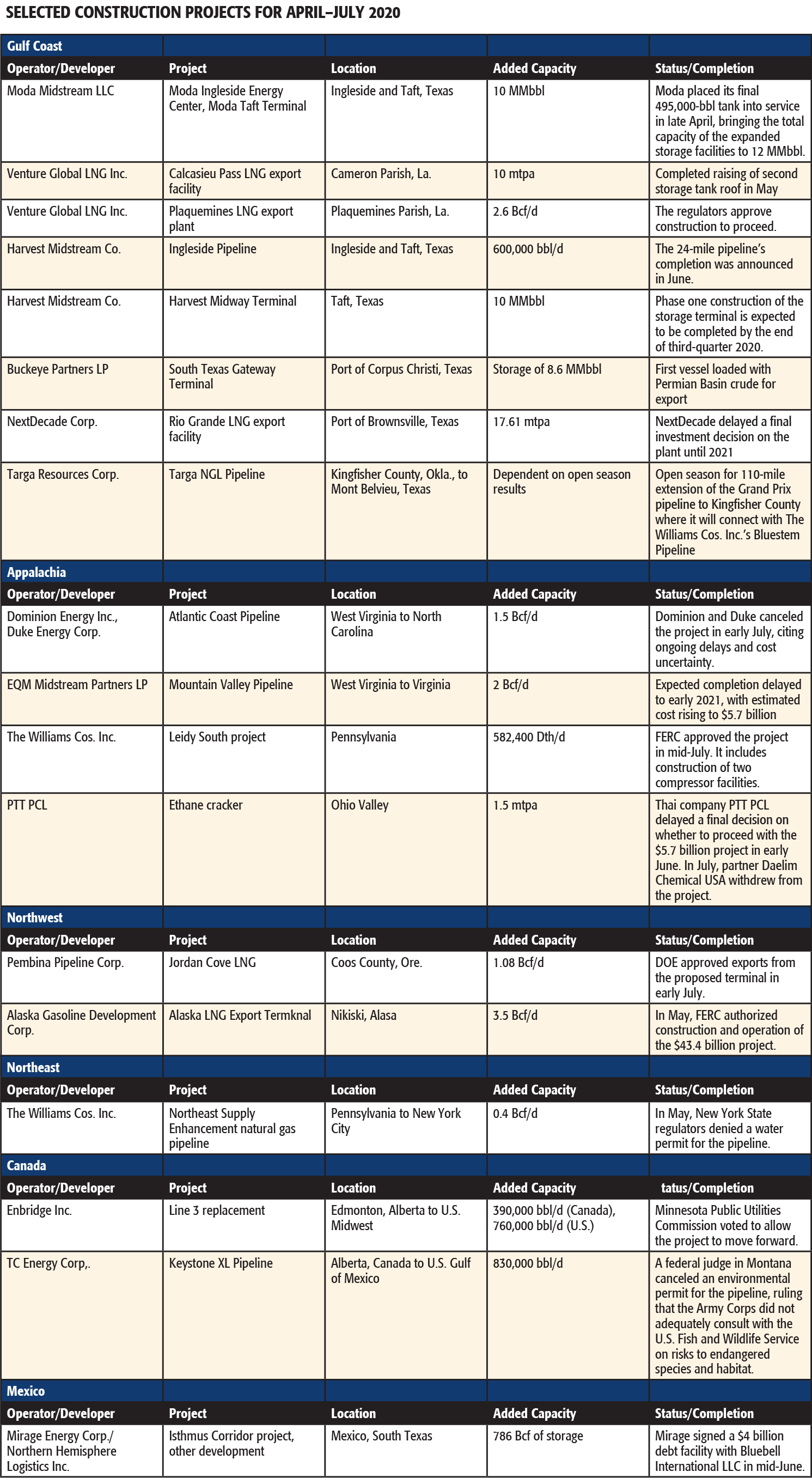

Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast again dominates the list of projects because demand has shifted down the value chain to storage and terminals, and away from wellhead-proximity needs like gathering and processing and pipelines.

In late April, Moda Midstream LLC completed the 10-MMbbl expansion of its Moda Ingleside Energy Center (MIEC) in Ingleside, Texas, and Moda Taft Terminal in Taft, Texas. Placing the final 495,000-bbl tank into service brought total storage capacity to 12 MMbbl.

“Bringing 10 million barrels of storage online in just over a year and a half is a major accomplishment,” Moda’s president and CEO, Bo McCall, said.

The company, though, isn’t done. Work has begun to add 3.5 MMbbl of crude storage at MIEC, bringing the total to 15.5 MMbbl when this expansion phase is completed, probably later this year. Other expansions are in the planning stages pending discussions with customers.

Venture Global LNG Inc. was also in a hurry to complete its projects, raising the 1.8-MMlb tank dome and assembly of its second LNG storage tank at its Calcasieu Pass LNG export facility in Louisiana during a 1 hour and 20 minute operation in May, three months ahead of schedule. Installation of the gas-insulated switchgear was performed on schedule, too.

In mid-June, regulators gave the company a green light to move forward with limited site preparation of its proposed Plaquemines LNG export plant in Louisiana. A decision is expected later in the year, but if Venture Global chooses to proceed, it could be the only U.S. LNG project to begin construction in 2020 as coronavirus-related delays have pushed back plans of other developers. The $8.5 billion Plaquemines plant is scheduled to enter service in 2023.

Plaquemines is designed to produce up to 20 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) of LNG, equal to about 2.6 Bcf/d of natural gas. Analysts estimated the plant will cost about $8.5 billion. Harvest Midstream Co. also kept an eye on the clock, completing its Ingleside Pipeline on time and providing customers with direct access to all three terminals in Ingleside.

“This is one of the fastest growing export centers on the Gulf Coast and we are excited to share this growth with our customers,” Sean Kolassa, president of Harvest Midstream, said in June. The 24-mile, 24-inch oil pipeline has a capacity of 600,000 bbl/d with Harvest Eagle Ford pipeline systems able to feed it with up to 380,000 bbl/d. It began transporting volumes to the Flint Hills Resources Ingleside Terminal first, followed by service to the South Texas Gateway Terminal and the MIEC.

The pipe originates at the Harvest Midway Terminal, which covers 160 acres in Taft, Texas. By the end of the third quarter, Phase 1 construction of the terminal is expected to be completed. The terminal could hold up to 10 MMbbl of crude storage.

Crude oil from the Permian Basin was loaded onto a vessel at the South Texas Gateway in July, a first for the Buckeye Partners LP-operated facility. The terminal is a joint venture, 50% owned and operated by Buckeye Partners. Phillips 66 Partners LP and Marathon Petroleum Corp. each have a 25% ownership interest.

When fully operational, South Texas Gateway’s petroleum products storage capacity will total 8.6 MMbbl with the potential to expand to 10 MMbbl, and up to 800,000 bbl/d of throughput capacity at two deepwater docks. Targa Resources Corp. announced an open season for an extension to its Grand Prix pipeline system.

The 110-mile extension of Grand Prix will connect with Williams’ Bluestem Pipeline in Kingfisher County, Okla., to move NGL to Mont Belvieu, Texas. Not all of the news emanating from the Gulf Coast was as upbeat. In May, NextDecade Corp. said it will not decide whether to build the proposed Rio Grande LNG export plant in Texas until 2021. The company had announced it would make its final investment decision this year but backed off as it assessed demand destruction from the coronavirus to global LNG.

Appalachia

Dominion Energy and Duke Energy announced the cancellation of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline on July 5. The project costs, estimated at $4.5 billion to $5 billion when it began in 2014, had ballooned to at least $8 billion. The companies cited ongoing delays and increasing cost uncertainty, which threatened the pipeline’s economic viability.

EQM Midstream Partners LP’s Mountain Valley Pipeline, which is 92% complete, also experienced troubles. The project, originally expected to be finished in late 2018 at a cost of about $3.5 billion, was delayed to early 2021 with a new cost estimate of about $5.7 billion. Industry analysts, however, were skeptical that the company could meet the new deadline, noting the same legal issue concerning the Corps that tripped up DAPL is in play with Mountain Valley and other U.S. pipelines.

“Mountain Valley faces litigation risk on several upcoming permitting decisions,” Height Capital Markets said.

A different project, PTT PCL’s $5.7 billion ethane cracker in Ohio, also suffered a delay. The cause was the global economic slowdown and the accompanying demand collapse with an already saturated plastics market. The Thai chemical company had planned a final investment decision in the first half of 2020 but in early June put it off until first-quarter 2021.

In July, the company’s partner, South Korea’s Daelim Industrial Co. Ltd., withdrew completely. The facility is planned to produce about 1.5 mtpa of ethylene.

Construction is expected to take four to six years.

Not all projects in Appalachia were in retreat. In late July, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission granted approval for The Williams Cos. Inc. to move forward with its Leidy South Project. It is expected to increase natural gas pipeline capacity by 582,400 Dth/d for Atlantic Seaboard markets by the 2021-2022 winter heating season.

With the exception of two new compressor facilities, Leidy South’s infrastructure addition will be relatively modest because it will rely on existing facilities in Pennsylvania. Alan Armstrong, president and CEO, stressed the clean energy aspect of the project in his announcement.

“There remain more than 80 coal plants in the states Transco serves that can potentially be displaced by clean, efficient and affordable natural gas,” he said.

Recommended Reading

Marathon Petroleum Sets 2024 Capex at $1.25 Billion

2024-01-30 - Marathon Petroleum Corp. eyes standalone capex at $1.25 billion in 2024, down 10% compared to $1.4 billion in 2023 as it focuses on cost reduction and margin enhancement projects.

Humble Midstream II, Quantum Capital Form Partnership for Infrastructure Projects

2024-01-30 - Humble Midstream II Partners and Quantum Capital Group’s partnership will promote a focus on energy transition infrastructure.

Hess Corp. Boosts Bakken Output, Drilling Ahead of Chevron Merger

2024-01-31 - Hess Corp. increased its drilling activity and output from the Bakken play of North Dakota during the fourth quarter, the E&P reported in its latest earnings.

The OGInterview: Petrie Partners a Big Deal Among Investment Banks

2024-02-01 - In this OGInterview, Hart Energy's Chris Mathews sat down with Petrie Partners—perhaps not the biggest or flashiest investment bank around, but after over two decades, the firm has been around the block more than most.

Some Payne, But Mostly Gain for H&P in Q4 2023

2024-01-31 - Helmerich & Payne’s revenue grew internationally and in North America but declined in the Gulf of Mexico compared to the previous quarter.