Presented by:

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the April 2021 issue of Midstream Business magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

In the story of takeaway capacity for the Permian Basin, crude oil pipelines represent Papa Bear—too big, too much capacity for current production. Natural gas pipelines are Baby Bear—just right, i.e., capacity in sync with output (at least for the moment).

And Mama Bear? In this metaphor, the overworked mom is saddled with the “not enough” label. She has been laboring to overcome bottlenecks and transport hydrocarbons to market for so long that she deserves some hibernation time. At least until production ramps up enough to warrant another round of infrastructure overbuilding.

The cyclical nature of the oil and gas business could buttress the argument that “overbuild” is just another term for “ahead of its time.” What cannot be argued is that, in 2021, oil pipeline projects in service and on the way offer considerably more capacity than production can fill.

“Production is probably going to stay flat at best this year,” Peter Fasullo, principal at EnVantage Inc., told Midstream Business. “The reason why so much crude takeaway was built is because everybody was anticipating the growth would continue. I think what’s going to happen is, there’s going to be a real fight for market share over time.”

Fasullo estimates that oil pipeline takeaway utilization in the Permian is less than 60%. That figure comes from subtracting production from capacity, then subtracting the volume of crude delivered to local refineries. Historically, the lion’s share of Permian production headed to the Cushing, Okla., oil storage hub. Then the unconventional revolution came to town.

Houston vs. Corpus Christi

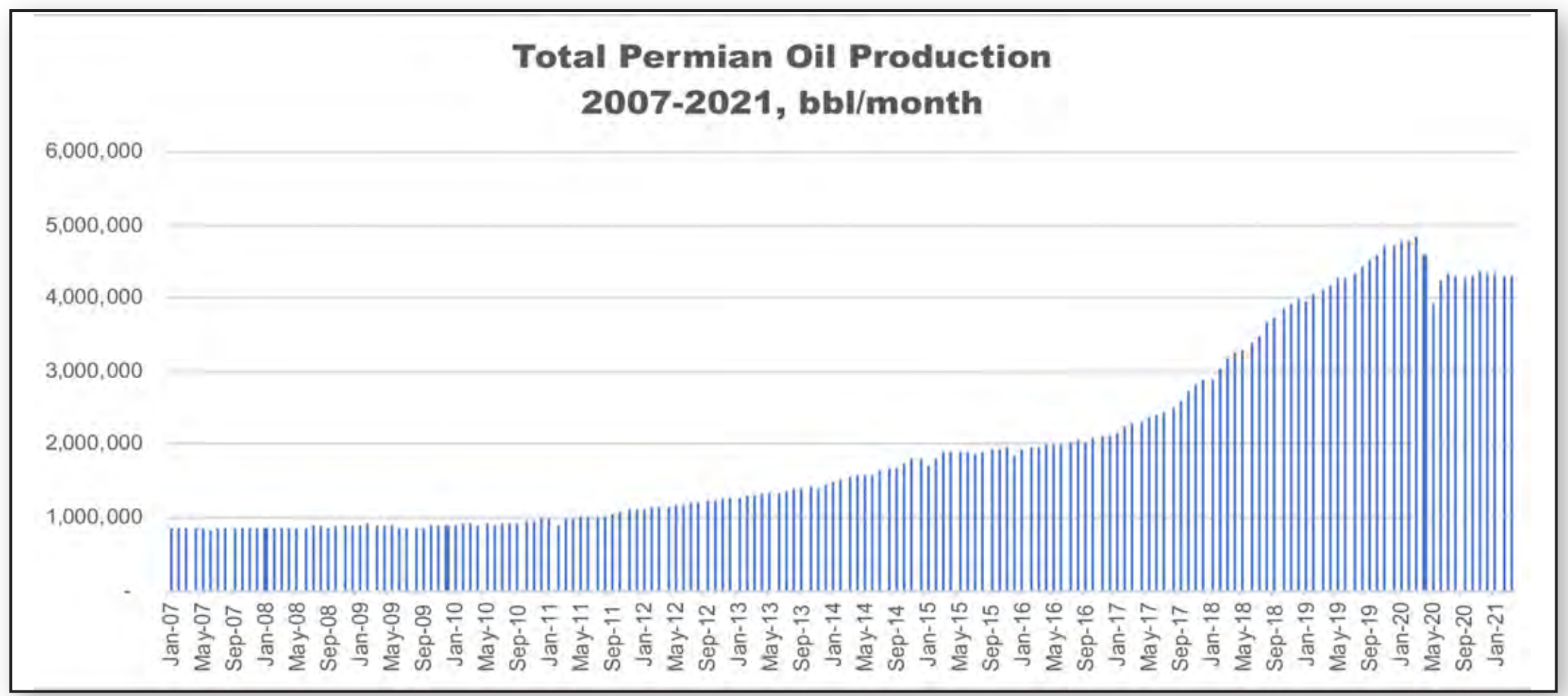

The Permian’s meteoric rise in production in the past decade roused the midstream into a buildout frenzy. Basin oil production passed 1 million barrels (MMbbl) per month in May 2011, according to Energy Information Administration data. It would take more than five years to crack 2 MMbbl in July 2016. Only 19 months later, production topped 3 MMbbl in February 2018 and just 12 months later, in February 2019, Permian production eclipsed 4 MMbbl. Production peaked at 4.85 MMbbl in March 2020, just as the COVID-19 pandemic kneecapped the global economy and energy demand plummeted. Even so, Permian production since that time has only dipped below 4 MMbbl per month once, in May 2020. Production in February 2021 was about 4.3 MMbbl.

“In 2015, ’16, ’17, we were operating well over 90% of capacity on the crude takeaway situation,” Fasullo said. “That’s what spurred a lot of people to say, ‘Hey, we need more pipe if the Permian’s going to continue to grow.’ And they did their job. They put more pipe in, and the problem is, it’s just too much right now given where production is ending up.”

As pipeline companies scrambled to build and keep up with ever-greater volumes coming out of the basin, two primary targets emerged as destinations on the Gulf Coast: Houston and Corpus Christi.

The Port of Corpus Christi offered less congestion and is closer to deep water than the Port of Houston, allowing it to handle larger tankers. It’s also cheaper to transport oil to the smaller port.

“However, Corpus lacks the optionality you have in the Houston area where you can network with more pipelines. You get more refinery capacity in the greater Houston area, and you’ve got more storage,” Fasullo said. There is also a slightly higher price to be gained at Houston, he said. “It’s kind of like going to Grand Central Station versus going to just a regional terminal.”

But the battle over moving scarce oil is not just between ports. Pipeline operators are also fiercely defending their market share while seeking to poach volumes off of competitors’ pipes, especially volumes that belong to the strongest producers. Even those producers that were not in the best financial shape may be able to score a better deal by switching to a different pipeline, Fasullo said, but the larger, more stable E&Ps can count on being wooed the most. If and when the producers switch, their oil will probably be headed to Houston.

“I think [pipelines] going to the Houston area will have an advantage over the long run over those going through the Corpus area if production stays fairly flat for a while,” he said.

Gas status

“Right now, we are adequately piped for natural gas evacuation from the Permian,” Terry Ciliske, principal at EnVantage, told Midstream Business. That is partly due to wintertime demand. “By summer, we should have excess capacity.”

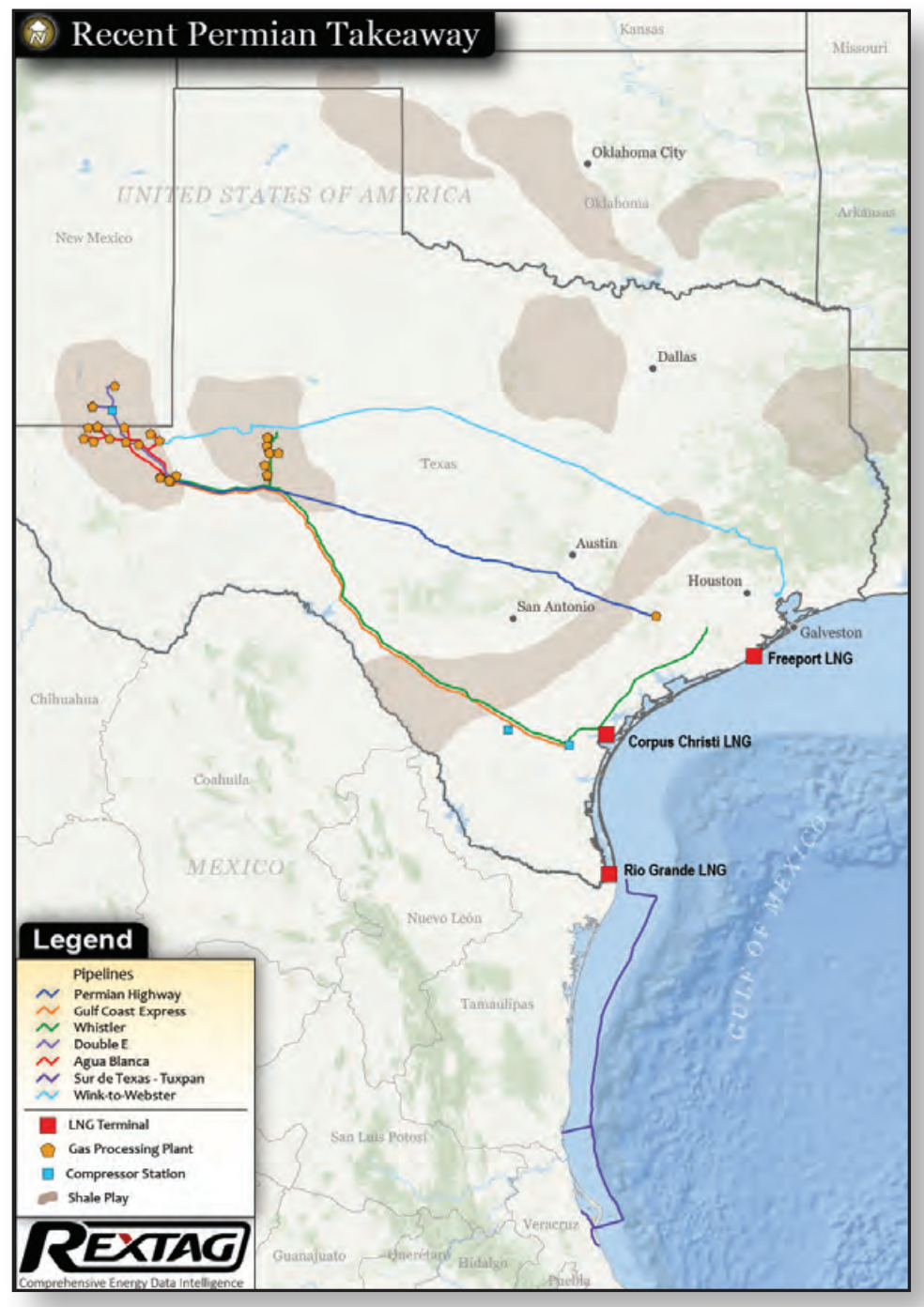

The game-changer is Kinder Morgan Inc.’s Permian Highway Pipeline, which went into commercial service in January. The 430-mile, 42-in. pipe delivers natural gas from the Waha hub to Katy, Texas area, with connections to the U.S. Gulf Coast and Mexico markets with a capacity of 2.1 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d). Kinder, EagleClaw Midstream and Altus Midstream each own a 26.6% interest in the line, with Kinder as operator. The remaining share is held by a shipper.

Permian Highway is fully subscribed under 10-year agreements. There are seven committed shippers, East Daley Capital Advisors said in a recent East Daley Midstream Navigator report. Most of the committed capacity is taken up by original partners Apache Corp., EagleClaw and Exxon Mobil Corp. Other Permian producers likely make up the rest of the list, East Daley said.

“The agreements likely offer producer counterparties a fixed Gulf Coast price discount, effectively eliminating spread risk for KMI,” the analysts said.

Sometime around mid-year, Ciliske expects the Whistler Pipeline to come online. The project is a joint venture of WhiteWater Midstream LLC, MPLX LP, West Texas Gas Inc. and Stonepeak Infrastructure Partners and will be able to move up to 2 Bcf/d from the Permian to the Agua Dulce hub southwest of Corpus Christi. Also on the plus side, he said, are infrastructure completions in Mexico, enhancing the amount of gas that can be transported from the Permian to northwestern Mexico.

“All these changes have taken the pressure off pricing in the Permian,” Ciliske said. “Natural gas basis has improved considerably, such that there are relatively tight differentials between Waha, for example, and other parts of Texas.”

Rig counts are starting to move up again but that trend is oil-driven, and the numbers are still well below the peaks of the past two to three years. In late February, the U.S. total count was just under 400 rigs, or about half the count of a year earlier. Still, it was well above the record low of 244 in August 2020. That means, he said, that declines in oil and gas production are likely to have bottomed out. Production growth during the next two years is expected to be modest.

EnVantage projects a Permian production increase of 1.5 Bcf/d to 2 Bcf/d by year-end 2022 from current levels.

“We’ve just started up a 2 Bcf pipeline,” Ciliske said. “We’re getting ready to start up another 2 Bcf/d pipeline, so there should be more than adequate capacity to handle the growth of natural gas over the next couple of years.” The projection relies on some presumptions:

- Volumes of gas heading east and to California remain within norms of recent years;

- Exports to Mexico continue to increase modestly; and

- There continues to be adequate demand on the Permian’s older pipelines and its three new ones— Kinder’s Permian Highway and Gulf Coast Express, and the consortium’s Whistler—to absorb the volume.

“Now, what could be happening is that there is a competition on the eastern end of those new pipes vis-à-vis gas that’s sourced off of the interstates that have been bringing gas in from points East, whether it’s from the Marcellus or the Haynesville,” he said. “So, there may be some gas-on-gas competition in the region between Agua Dulce and Katy, Texas.”

Where will it go?

There are a lot of moving molecules in this market. Much of the increased production has been absorbed by two new LNG facilities on the Gulf Coast— Freeport LNG (15 mtpa capacity) and Cheniere Corpus Christi (15 mtpa capacity when the third train goes into service), both of which went into service in 2019. The startup of TC Energy Corp.’s Sur de Texas–Tuxpan Pipeline, which moves gas from near Brownsville, Texas, below the Gulf of Mexico to power plants in Altamira, Tamaulipas and Tuxpan in the Mexican state of Veracruz.

The 478-mile Sur de Texas–Tuxpan has a nameplate capacity of 2.6 Bcf/d but has been flowing in the range of 600 MMcf/d to 800 MMcf/d in recent months because infrastructure construction has lagged on the tail end of the pipe.

“Theoretically, if the infrastructure and the demand in central/southern Mexico can be adequately piped and the demand is there, there is sufficient capacity to move incrementally roughly about 1 Bcf/d of gas south of the border, which would help alleviate some of this gas-on-gas competition in South Texas,” Ciliske said.

In the near term, LNG demand in the Gulf Coast region has topped out. Freeport and Cheniere Corpus Christi can handle between 4 Bcf/d and 4.5 Bcf/d at peak, but that demand is met now, before Whistler goes into service. Assuming there is sufficient gas to fill up Whistler, gas-on-gas competition could intensify during the shoulder months.

Longer term, continued drilling and growth in the Permian beyond 2022 would support new pipeline projects aimed toward the Gulf Coast. If modest demand growth continues in Mexico, the existing systems would be better utilized, he said, and additional volumes could start flowing on Sur de Texas– Tuxpan to help absorb any additional growth out of the Permian. But the key word regarding growth expectations remains “modest.”

“At the growth rates that we’re looking at right now, based on rig counts etc., we would not anticipate that additional gas capacity out of the Permian would be necessary prior to about 2024,” Ciliske said.

If more gas pipeline capacity is added too soon, it could create gason-gas competition between West Texas and eastern-sourced gas (from Appalachia) and result in a short-term price weakness. Whether that happens depends to some extent on how the second round of LNG export terminals shakes out. As terminals come online, they will provide demand for higher volumes of gas—that is, if they are built. In late January, NextDecade Corp. scrapped its Galveston Bay LNG site in Texas City, Texas, citing the potential for prolonged uncertainty over whether it would be able to proceed with construction. In fact, it would have taken a literal act of Congress to allow for the environmental development of the site.

NextDecade’s Rio Grande LNG, in late-stage development at the Port of Brownsville, Texas, will definitely move forward, the company said. But even that project’s status has raised eyebrows. In November, French gas and power utility Engie SA withdrew from its $7 billion deal to purchase LNG from the terminal under pressure from the French government over climate concerns. The deal breaker was the feedstock natural gas that was extracted via fracking and the methane emissions that accompany it. As new trains come online (or not) at existing facilities in the region, the demand scenario could experience other shifts. But those factors really don’t come into play until 2024. For now, Permian gas takeaway is in Baby Bear status. This is as good as it gets.

“It’s the best news the Permian has seen in a number of years with regard to capacity,” Ciliske said. “And capacity is going to a good, valued market as opposed to taking the route in which it would have to compete with Canadian gas and Rockies gas in the Midwest. That was the least desirable path for Permian gas.”

More discipline

Downcycles have led customarily to upcycles in the oil patch when a glut depressed prices so much that demand naturally increased. Soon, increased production would fill up the formerly overbuilt pipeline system, and the “capacity constraint” mantra would be heard again. And it very well might happen that way again. And it might not.

“The nature of the business has changed to some degree to where producers are going to have more discipline,” Fasullo said. “In the past, say, prior to 2020, the main goal was, in a lot of cases, increased volumes.”

For some, generating those larger volumes led to high debt situations and insufficient returns to satisfy investors. Then the COVID-19 pandemic crashed the global economy, resulting in mergers, bankruptcies and a beleaguered E&P sector licking its wounds. Even among those making a living off the celebrated rock of the Permian Basin.

“Just because prices go up, you may not see the type of runaway production that we had prior to 2020, where you just had a huge increase in production taking place,” he said. “I mean, the rock is very good, but I think it’s just going to be produced in a more disciplined way.”

Fasullo expects production to grow again but growing oil pipeline infrastructure may take a bit longer.

“The problem is, we put a lot of capacity in the ground,” he said. “So, if you’re operating at less than 60% now, it’s just going to take time for things to get back.”

Fasullo estimates that Permian oil takeaway capacity is well above 7.6 MMbbl/d but production is only at about 4.2 MMbbl/d. The volume that goes to local refineries could total 300,000 bbl to 350,000 bbl. The rest goes into the pipes. The situation is the same for NGL. There is takeaway and fractionation capacity aplenty, which forces fights over market share.

“In a sort of ironic way, our NGL production is flat at best right now, but demand for our NGL is extremely high,” he said. “We’re exporting record amounts but the problem is, we’re having to draw down inventories to supply that international pull for LPGs. And so that’s creating a squeeze.”

The last time the propane supply was as low in number of days was in 2014, the winter of the polar vortex. But that was weather driven, Fasullo said. The market tightness now is internationally driven, although the Presidents Day freeze in Texas drove the price of propane over $1 a gallon. Still, he said, that’s not enough to convince a producer in the Permian to drill for crude to make money on propane.

Wolf at the door

Back to the bears. They’re at home, strategizing about how to get by until Papa Bear’s oil pipeline overcapacity can be balanced by production growth without developing the kinds of takeaway constraints that will stress out Mama Bear again. Suddenly, the big, bad regulatory wolf appears at the door and threatens to blow their house down. Different story altogether? Actually, the essence is quite relevant so just bear with it.

“If the Trump administration had continued, you would have thought, ‘OK, maybe this industry is going to rebound,’” Fasullo said. “We knew the Biden administration was going to be tough on traditional energy. The cancellation of [KXL] however, this may be the first of many things to come.”

It may not be the feared ban on fracking, but more regulations or actions along those lines could constrain E&P efforts going forward, he said, even if the economics warrant expanding production. Fasullo is aware of predictions that constraints on U.S. production will tighten oil supplies and bolster prices but he has his doubts. There is, after all, the reality that OPEC is holding back production of about 7 MMbbl/d.

“I’m trying to think of what could actually just catalyze production upward in a big way, and I can’t come up with a reason for it,” he said. “Over the next couple of years, at least, production is going to stay flat, or it may actually drop a little bit.”

Recommended Reading

US Drillers Add Most Oil, Gas Rigs in a Week Since September

2024-03-15 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, rose by seven to 629 in the week to March 15.

US Gas Rig Count Falls to Lowest Since January 2022

2024-03-22 - The combined oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, fell by five to 624 in the week to March 22.

US Drillers Cut Oil, Gas Rigs for Third Week in a Row

2024-04-05 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, fell by one to 620 in the week to April 5, the lowest since early February.

US Drillers Add Oil, Gas Rigs for First Time in Five Weeks

2024-04-19 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, rose by two to 619 in the week to April 19.

US Drillers Cut Oil, Gas Rigs for Fourth Week in a Row-Baker Hughes

2024-04-12 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, fell by three to 617 in the week to April 12, the lowest since November.