Production from U.S. unconventional plays—boosted by advances in completion technology and techniques—has undoubtedly transformed the oil and gas scene both in the U.S. and abroad. However, low recovery rates for shale oil and gas plus steep declines for wells show there is still room for improvement. Some are turning to microseismic and refracks to better results given today’s market conditions.

“Beating the decline curve in unconventional reservoirs requires continuous drilling and completion of new wells. This can be costly and time consuming,” Sudhendu Kashikar, vice president of completions evaluation for MicroSeismic Inc., explained in a webcast this week. “Refracking provides a lower cost alternative to drilling new wells. Refracking generally provides increased production from existing wells at a much lower cost.”

However, aiming to stimulate new rock by refracking is not without challenges.

For starters, performance can be an issue with variation in coverage and impact of treatment pressures. Most refracks today are done without mechanical isolation, opening all stages and perf clusters to fluid flow.

“We try to achieve isolation using various types of divergers to help progress the refrack along the lateral from the heel (of the well) to the toe; however, miscroseismic observation shows significant variation in achieving complete re-stimulation of the lateral,” he added.

The key challenge is determining when and where new fractures are being created.

He compared surface microseismic data acquired during initial hydraulic fracturing to microseismic data acquired during a refrack, which followed several years of production.

An overlay revealed evidence of depleted fractures that had been reactivated as well as microseismic activity in regions where no such activity existed with the original frack. “We can conclude that we have succeeded in creating new fractures during this refrack program,” he said.

Comparing the two results, “First, generally the refrack azimuth is the same as the azimuth of the original fracks. There is limited evidence of any fracture reorientation during this refrack,” he explained. “Finally, the degree of depletion prior to starting the refrack certainly impacts the results.” Once we had the luxury of acquiring microseismic data from the original and the refrack ̶ many of the wells being refracked today did not have microseismic data from the original well ̶ the challenge then becomes ‘how can one distinguish new rock being stimulate versus activating or restimulating existing depleted fractures?’ ”

This is where microseismic and looking at the initial shut-in pressure (ISIP) can help.

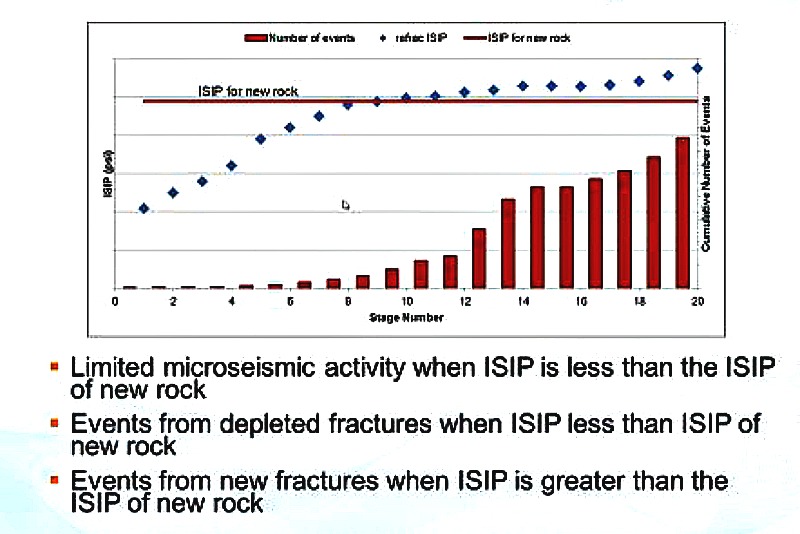

Kashikar used a chart to make his point.

New fracks or reactivation of existing fracks

The X axis shows the stage number during the refrack, while the primary Y axis shows the ISIP for each stage. The solid red line represents the ISIP during the original frack, while the second vertical axis (right) illustrates the miscroseismic activity as the refrack job progresses.

Key observations:

- Several pumping cycles and pumping cycles pass before there is any significant microseismic activity;

- The ISIPs in the initial stages are lower than the ISIPs recorded during the original frack, indicating fluid being pumped early on is trying overcome depletion and not resulting in significant microseismic activity;

- Once the ISIP reaches or exceeds the ISIP for new rock, there is a jump in microseismic activity. “Microseismic events recorded beyond this point most likely belong to new fractures that are being created or new rock being stimulated,” Kashikar said.

“We can use the above information to create a map of depleted zones using the location of microseismic events recorded while the ISIP is less than that of the new rock,” he explained.

“Similarly, the events that happened at ISIPs equal to or greater than the ISIPs for new rock can be used to create a map of new fractures that were created during the re-stimulation.

“Observations from other wells also indicate that it is possible to get an accurate picture of depleted fractures by pressuring the wellbore prior to starting the frack,” he continued. “This provides a mechanism to identify and quantify the additional stimulated rock that was generated by the refrack.”

Several companies think refracks can lead to more production, and some are already having success.

Speaking during last year’s DUG Midcontinent conference, Mark Castell, vice president, Oklahoma assets, for PetroQuest Energy, predicted the future would likely hold more refracturing of wells. He called it the renaissance of refracking.

“I think you’re going to see more of it with time as we get into the later life of shale plays and the rates are dropping off,” he said.

Contact the author, Velda Addison, at vaddison@hartenergy.com.