Consolidation, particularly between large independents and small and mid-size companies, seems likely to be part of the balance of deal making in 2019. (Source: Illustration by Rick Corrigan)

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the March 2019 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

As 2018 unfolded, buyers bargained and sellers were willing to entertain offers. The backlog for A&D was deep. Oil prices flirted with $75 per barrel (bbl). Yet something was off.

Victor Barcot, managing director at Houlihan Lokey, calls 2018 “the missed upcycle.” Even as oil prices escalated and deals were discussed, “we were kind of looking at each other across the table and saying, ‘yeah, but this sure feels like a $40 environment,’” Barcot told Oil and Gas Investor.

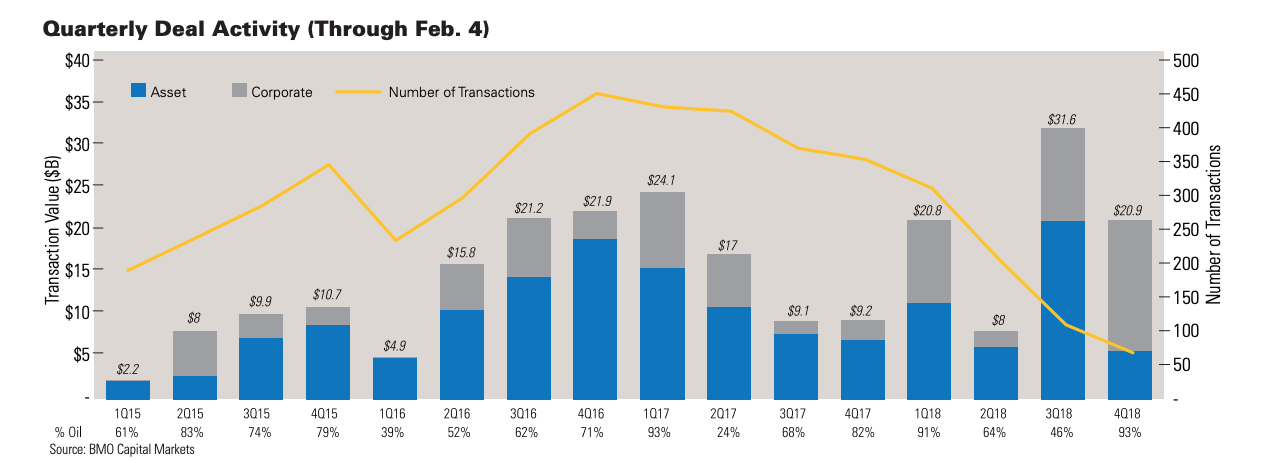

Measured by value, 2018 was easy to see as a return to form for M&A, with overall deal value up 26% compared to 2017, according to the January report, “Unrealized Potential,” by Deloitte. Multibillion-dollar deals and mergers uniting big-name, independent oil and gas companies flourished. But the large deals obscured a slowdown in closings for smaller and mid-size deals.

On June 27, a barrel of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude reached its highest spot price in three years, seven months and 17 days at $77.41/bbl, according to U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) data. Spot prices spent more than one-fifth of the year’s trading days above $70.

“It ended up being somewhat of a disappointing year from a transactional standpoint,” Barcot said. “To sum it up, no one really felt like it was sustainable.

“No one benefitted from it. The clients didn’t benefit from it.”

with Houlihan Lokey, calls 2018

“the missed upcycle,” noting that

even as the oil price environment recovered,

“no one benefited from it.”

Across all sectors, the oil and gas industry spent more than $300 billion on deals, the highest value since 2014, according to a January presentation by PwC. However, about $120 billion of those transactions were restructurings and simplifications of midstream MLPs, which converted to C-corp business structures.

In the upstream, M&A values soared—on paper, and specifically share certificates. Megadeals of at least $1 billion powered the overall U.S. upstream deal market to an $80 billion year. But for independent E&Ps, the currency of choice was common stock.

The top 10 largest upstream deals by value, strewn along the year from February to November, totaled $49.6 billion, or more than half of all the year’s upstream deal value, according to Oil and Gas Investor data. Major oil company BP Plc’s purchase of U.S. assets from BHP Billiton, now BHP Group Plc, led all upstream deals at $10.5 billion in cash.

However, public companies such as Concho Resources Inc. and RSP Permian Inc., and Diamondback Energy Inc. and Energen Corp., merged companies in the Permian Basin by putting virtually zero cash on the table. Among U.S. independent E&Ps and excluding BP, the 10 largest upstream deals totaled about $42 billion, roughly 81% of which was paid using stock, according to Oil and Gas Investor analysis.

However, the overall rate of 2018 transactions fell 16%, or by 35 deals, compared with 2017, PwC said.

“When you look at 2018 on a deal volume basis, the 186 deals were well below our average of about 200 deals over the last nine or 10 years,” said Joe Dunleavy, PwC’s U.S. deals leader, in a January web presentation.

Mid-sized and smaller deals sometimes didn’t get done or did so at a slackened pace from years past.

Fourth-quarter Blues

For an industry that prides itself on optimism, the end of the year was a fog of pessimism.

With gallows humor, William A. Marko, managing director at Jefferies LLC, joked to a colleague, “Well, at least up to now, we’ve had a decade-long run.

“The year took a bad turn,” Marko said, citing falling oil prices, the continued volatility of the general stock market, the unknowns of tariffs and trade wars. Interest rates also rose, and with a “malaise in the public capital equity markets for energy, it’s hard to do deals at this moment,” he said in January.

“It opened like a lion and ended with a thud,” Marko said of 2018. “The fourth quarter was awful.”

The rest of 2018 saw a see-sawing of deal activity—the second quarter was miserable, the third quarter fabulous—and the usual suspects being haggled over.

with a thud,” William A. Marko,

managing director at Jefferies LLC,

said of 2018, adding that the

fourth quarter was “simply awful.”

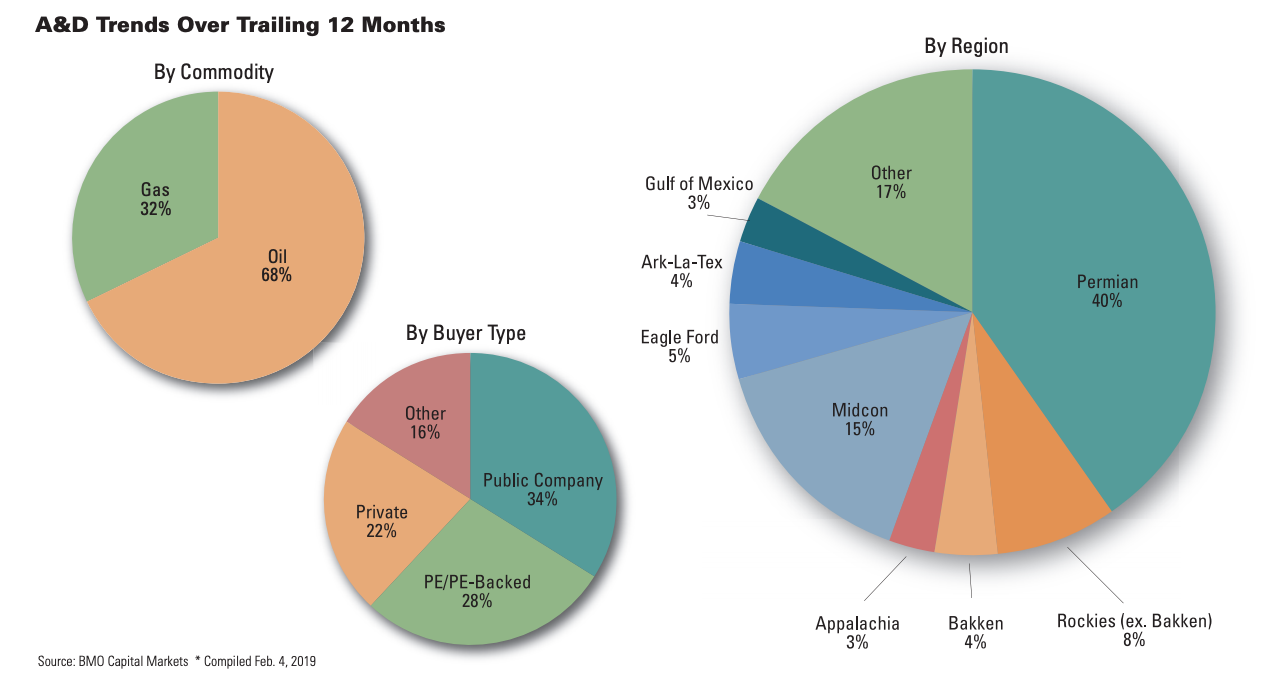

The Permian Basin lead all basins both in value and volume with 33 deals tallying $36 billion, followed by the Bakken at $21 billion, PwC said.

Deloitte added that, “in any given quarter, the weighted average dollar per acre paid by companies for Permian assets is two to five times higher than prices for acreage in other basins.”

In the Eagle Ford, about $8 billion in deal value opened up and $10 billion in the Scoop/Stack, Deloitte said.

But in the M&A trenches, advisers and business development professionals saw the year close in stark contrast to the megamergers and hearty third quarter.

From early October through the end of 2018, spot prices dropped by $30.68/bbl, ending at $44.48, the lowest price of the year. Average fourth-quarter WTI prices fell 15% compared to the third quarter’s average.

Fourth-quarter deal value fell by 37% compared to the third quarter, excluding dropdown deals and related party transactions, PwC said.

Already announced but unclosed mergers may yet face additional hurdles, Marko said.

“The public mergers are under a lot of pressure at this moment,” Marko said. “I think the intention by many is to try to get them closed, and we’ll see how things turn out.”

Evidence of that pressure surfaced in late December, as sliding oil prices and relentlessly falling stock prices played a role in Earthstone Energy Inc. nixing its $950 million deal for Sabalo Energy LLC. Denbury Resources Inc.’s $1.7 billion deal for Penn Virginia Corp. is also under fire by some investors who consider Denbury’s offer too low. And Denbury’s share price averaged a 46% decline from Oct. 28 through early January. [Editor's note: Denbury and Penn Virginia agreed to mutually terminate their merger March 21, 2019.]

As first-quarter 2019 begins, deals and larger consolidation are at risk, especially as oil prices continue to stall out and potential buyers’ stock prices continue to swoon, said Austin Elam, an attorney with Haynes and Boone LLP’s Oil and Gas Practice Group.

“Until prices stabilize, there is an expectation that A&D activity for oil-focused basins will slow, including a pause to increased industry consolidations,” Elam told Oil and Gas Investor.

Capped Market

In first-quarter 2018, Houlihan Lokey had seven A&D sell-side mandates and Barcot expected them all to close, he said. Oil prices were at a healthy level. Clients expressed interest in transacting.

But as the summer neared and the second quarter began, potential buyers began to pull back, he said.

“The buyers were … falling through because of funding. Funding wasn’t coming through,” Barcot said. “Access to capital markets seemed to be an issue for publics.”

Bolstered by epic-sized deals, M&A seemed on solid footing but hid the difficulty many public E&Ps faced. Even as companies show sustained efforts toward capital discipline, Barcot said, investors have made a fundamental shift in capital allocation away from the oil and gas space.

The hope had been that increased prices, E&Ps’ restrained spending and paying down debt would lure the market investors back in 2018, Elam said. That hasn’t helped E&Ps, however, which see their values continue to trail commodity price increases.

“The markets have reiterated the need for producers to demonstrate value through drilling within cash flow and to rationalize their balance sheet, relying less upon debt and equity issuances than in prior years,” he said. “Until producers can demonstrate that ability, public investor appetite for the upstream industry might remain depressed, continuing trends from 2018.”

Last year, companies played it safe by divesting noncore assets or consolidating with other producers. Shale producers also kept busy swapping acreage to create more contiguous blocks to allow for maximum lateral wells, Elam said.

Still, as oil prices have dropped precipitously, Marko said, times have changed at oil and gas companies. In early 2017, an executive vice president at Equinor noted that in 2014, the company needed $90/bbl to make money.

“In 2018, we’ll make money at $50,” the executive said.

Marko said that E&Ps are prepared, should prices remain in a long-term funk.

“That’s kind of a microcosm of what a lot of companies have done. They’ve really looked at cost structure,” Marko said. He noted that ConocoPhillips Co. evaluates its portfolio by cost of supply and how low prices can get while the company still earns 10% returns at different price levels. Some of those prices are as low as $30/bbl, he said.

“They’ve really scrubbed the portfolio so they can live in a lower-cost environment,” he said.

‘The Fear Index’

With public companies hamstrung by the markets, essentially one subset group of buyers—private equity—remained. “And they all knew they were the only buyers,” Barcot said.

However, private equity faces its own challenges, chief among them a path toward the exits. Partly that’s due to the cold shoulder markets continue to give IPOs and follow-on offerings.

Private-equity firms still command a huge stockpile of cash and demand remains strong, but private capital appears to be behaving cautiously, Marko said.

“There are probably more than 250 management teams, so there’s somebody out there looking at almost anything you could think of,” he said. “So there is demand to some extent for almost anything.”

Curt Karges, PwC managing director and energy leader, sees sentiment in the industry more negative that it was a year ago, despite oil at roughly the same price.

The rate of global growth, trade complexities, market volatility and rising interest rates are concerning, he said during the January presentation.

“I would call that sort of the fear index,” he said. “Added to that is the actual experience by investors.”

Karges noted that private equity has invested in about 250 service companies, with 180 of those investments made prior to 2015 at relatively high valuations. Headed into 2018, many private-equity companies “believed they were going to be able to finally exit at a profit” for their older portfolio of investments.

But the industry as a whole saw “a lot of busted auctions. There’s still a bid-ask spread between owners of properties and prospective owners or investors.”

A scarcity of IPOs and lethargic market activity have also hampered private equity from finding the exits.

an expectation that A&D activity

for oil-focused basins will slow,

including a pause to increased

industry consolidations,” said

Austin Elam, an attorney at

Haynes and Boone LLP.

In the second half of 2018, public oil and gas companies’ secondary offering average $1.5 billion, down from an average $3.25 billion in the previous four quarters, according to PwC. For the nine months spanning the second, third and fourth quarters, only one IPO successfully launched, though at least 10 companies have expressed interest in going public, according to PwC.

E&Ps and particularly natural gas companies, most backed by private-equity capital, will be hard-pressed to make substantial moves in 2019, Marko said.

“You’ve got a number of Haynesville producers that have publicly stated ‘we’d like to go public,’” he said. “There’s no IPO market for energy in general and even less so for gas,” he said.

Investors have also pulled up stakes in the oil and gas industry in general, Barcot said. Prior to the 2014 and 2015 downturn, large-scale investors were allocating up to 15% to 17% of the entire capital allocation to the space. Since then, “the bucket of money” devoted to the space “has shrunk to 7% to 9% and we’re there permanently now,” he said.

With a “flight to quality, mature companies and vertically integrated companies such as ExxonMobil [Corp.] and ConocoPhillips performed well compared to the group,” he said. “Overall the sector’s down and is underperforming the broader market.”

2019 Themes

The road to M&A in 2019 may be as treacherous and full of blind curves as it’s been since the downturn.

The market volatility that began to stabilize in January will need to further settle before more megamergers or acquisitions kick off in 2019, said Kraig Grahmann, an attorney with Haynes and Boone.

Views of M&A vary widely, with speculation over what moves international oil companies have to make in the U.S. and how oil and gas pricing might make a difference. Consolidation, particularly between large independents and small and mid-size companies seems likely to be part of the balance of deal making, but cash flow will continue to be more of a motivator than raw acreage, deal makers and other industry observers said.

Grahmann sees 2019 M&A revolving around themes: a major or super-major making a transformative entry into a basin—or an independent E&P company exiting an asset that it acquired in a better price environment to pay down debt, return cash to shareholders or invest in its core assets.

Karges, however, said it appears that most of the majors have finished positioning in shale plays and will likely work toward lowering costs and improving drilling efficiency. While integrated companies have clearly become convinced that shale is part of their future, they also retain deepwater investments.

“They have established positions in the major shale regions, most notably the Permian,” he said.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR:

Key Areas To Watch

Acreage or production? Curt Karges, PwC managing director and energy leader, said that 2019 will likely “continue to see that investors will be buying cash flow, not acreage.” Companies will try to lower costs through scale, invest in technology and “balance spending money vs. monetizing prior investing.”

The Permian’s many remaining small- and mid-cap Permian pure plays will also be asking themselves serious questions about longevity or the ability to compete with their larger neighbors in productivity, costs and services, Greig Aitken, director, M&A research at Wood Mackenzie, said in a January report.

“How do they remain relevant to investors? We expect more combinations,” Aitken said.

Aitken also said that at least two material positions appear to be piquing the interest of buyers. One is EnCap Investments-backed Felix Energy Resources LLC’s Delaware Basin position. The other is Endeavor Energy Resources LLC, which holds more than 300,000 net acres in the Midland Basin.

“It is no surprise that Chevron [Corp.], ExxonMobil and Shell are rumored to have kicked Endeavor’s tires,” he said. “A deal in 2019 is not a foregone conclusion, but if Endeavor’s backers want a near-term exit, the IPO route looks like a nonstarter under current market conditions.”

QEP Resources Inc. has also engaged advisers to explore a possible sale after an activist investor offered to buy the company. Abraxas Corp., which has formally hired an adviser to sell its Bakken assets, is also a potential Permian buyout candidate.

Consolidation remains necessary in the Permian if the market is to strengthen, Barcot said.

“We have just way too many companies in the U.S. Fourteen or 15 independent companies in the Permian Basin is not sustainable,” Barcot said. “If I look at the outlook and the bright side of it is that reduced capital allocation in the sector, reduced oil prices are going to force some healthy transitions.”

Oil pricing will remain a key determinant in how deals flow in 2019, Karges said.

“Tell me what the oil price is going to be, and I’ll tell what M&A activity is,” Karges said. “Obviously, supply of oil is going to be there. The question is, what is the demand?”

Deflated oil prices will also likely mean companies will deal for low-risk, producing assets rather than undeveloped acreage, Deloitte said.

Oil demand is now more important that supply. Barcot, a former equity research analyst and CEO of a publicly traded E&P, said 2018 was the year he finally stopped looking to supply for answers to oil and gas pricing and deals.

The switchover to a demand-focused world appears to have become cemented in the minds of investors as well, he said. Even OPEC’s late push in December to install quotas did little to raise prices or stir the market.

Where peak oil production once was the obsession of oil companies, Barcot said that peak demand now appears to be driving the markets. Renewable energy is also sapping an increasingly larger share of electric generation.

U.S. crude oil production is still predicted to set annual records through 2027 and to remain at more than 14 MMbbl/d through 2040, according to the EIA’s 2019 energy outlook.

Barcot, however, said that demand is a fundamental question.

“We’ve sort of answered that we have unlimited supplies in the U.S.,” he said. “We’ve grown to this astronomical output figure, to where now private-equity firms are fighting over export terminals and deepwater docks to export our excess hydrocarbons.”

As the second half of the year came to a close, he said that “industry keeps trying to fix supply, but the reality is the investor universe, as the capital providers to this space and the buyers of the stock, they’re not focused on supply. Supply was answered from 2008 to 2014. Now it’s demand, peak demand.”

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Darren Barbee can be reached at dbarbee@hartenergy.com.

Recommended Reading

TotalEnergies Starts Production at Akpo West Offshore Nigeria

2024-02-07 - Subsea tieback expected to add 14,000 bbl/d of condensate by mid-year, and up to 4 MMcm/d of gas by 2028.

Well Logging Could Get a Makeover

2024-02-27 - Aramco’s KASHF robot, expected to deploy in 2025, will be able to operate in both vertical and horizontal segments of wellbores.

Shell Brings Deepwater Rydberg Subsea Tieback Onstream

2024-02-23 - The two-well Gulf of Mexico development will send 16,000 boe/d at peak rates to the Appomattox production semisubmersible.

E&P Highlights: Feb. 26, 2024

2024-02-26 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including interest in some projects changing hands and new contract awards.

Remotely Controlled Well Completion Carried Out at SNEPCo’s Bonga Field

2024-02-27 - Optime Subsea, which supplied the operation’s remotely operated controls system, says its technology reduces equipment from transportation lists and reduces operation time.