Southwest of Midland, Texas, Parsley Energy Inc.’s $2.3 billion purchase of Jagged Peak Energy Inc. illustrated that a smart, all- stock transaction with a low price premium could survive Wall Street’s otherwise withering reaction to deals. Photo by James L. Durbin.

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the April 2020 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

It was wild, like a first date, first oil, the first million-dollar check deposited in the bank. M&A lit the shale revolution like the pilot light of a great furnace that seemed capable of burning on forever.

And like a flame, it was wild, and then it wasn’t.

Shalepalooza is gone, and there’s no going back. But transaction advisers see a way forward. Tricky and treacherous, but forward.

“No question, it’s a tough environment,” said Art Krasny, managing director and head of A&D for Wells Fargo Securities.

outlook for the

year is shaped

by the tug of war

between the logic

of consolidation

and benefits of

scale on

one hand and

the worsening

conditions in

the commodity

and capital

markets on the

other,” said Art

Krasny, managing

director and head

of A&D for Wells

Fargo Securities.

Welcome to 2020 A&D, the sequel to a year that tore down any lingering hype over oil and gas asset values.

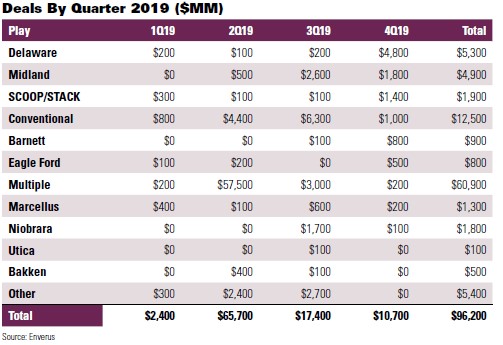

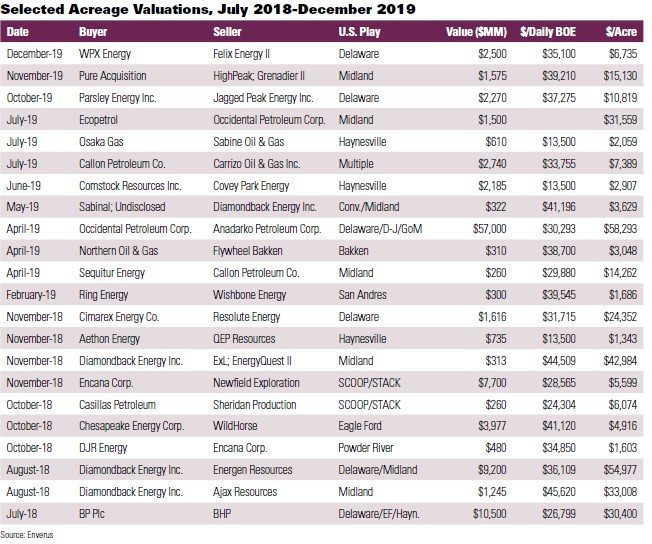

Even in the Delaware Basin, where two years ago leasehold cost $95,000 per acre, the bubble for acreage prices appeared to have burst. WPX Energy Inc.’s $2.5 billion purchase of Felix Energy II’s position averaged $6,700 per acre, according to Enverus. Likewise, Marathon Oil Corp. paid an average of $2,600 per acre in Ward and Winkler counties, Texas.

The market faces the push and pull of competing forces, Krasny told Investor.

“As we sit here in late February,” he said, “with natural gas prompt prices at $1.80 per MMBtu and $52 per barrel of oil and the global economic outlook shaken by the spread of the coronavirus, the M&A outlook for the year is shaped by the tug of war between the logic of consolidation and benefits of scale on one hand and the worsening conditions in the commodity and capital markets on the other.”

The fourth quarter of 2019 ended with a clunk for asset deals, but investors lit a signal fire for future mergers: when in doubt, underpay.

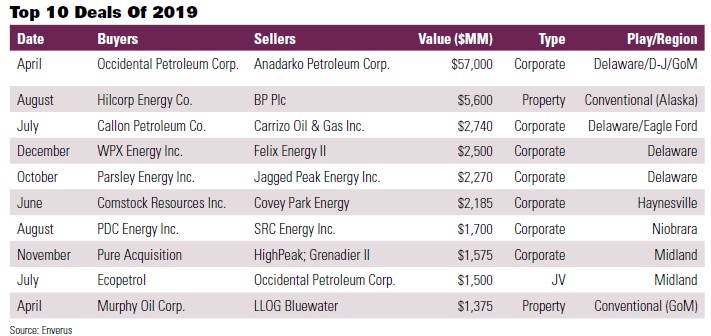

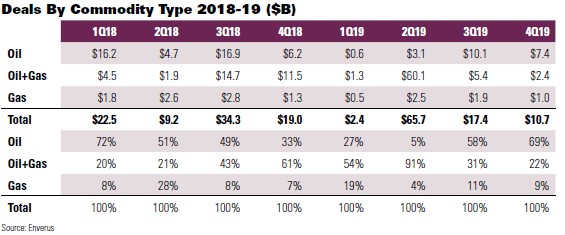

Over the course of the year, oil and gas deals racked up roughly 200 deals totaling roughly $100 billion, according to Enverus. But the dollar figure was somewhat illusory, with Enverus calculating that about 60% of total deal value was propped up by a single transaction—Occidental Petroleum Corp.’s purchase of Anadarko Petroleum Corp.

Overall, the largest deals centered on corporate consolidations as asset transactions dwindled.

Advisers expect the remainder of 2020 to tick by in the same fashion, with the Permian Basin still the center of attention but the deals there looking as they did in the fourth quarter, when the top three mergers were corporate consolidations. However, they also caution that it’s time to learn to live with uncertainty. The threat of the economy stalling, a pandemic and the abysmal performance of commodity prices leave M&A up in the air.

Payne rig. Parsley closed on Jagged Peak Energy’s West Texas leasehold in January. Photo by James L. Durbin.

Asset transactions, in particular, hit a wall in 2019, with many deals left on the table, said Bruce Cox, managing director for A&D at Citi Global Energy Group. “Only about 30% of public ... asset deals were completed in 2019 versus the typical 75%,” Cox said.

Likewise, Mark Nelson, executive director of A&D at CIBC Griffis & Small, saw a grim marketplace that will probably carry on throughout 2020.

“The reality is that Lower 48 asset sales in 2019 were about one-fifth of the 10-year average, both in deal count and total transaction value,” Nelson said. “We see a similar activity level in 2020 and expect public M&A to increase as the year unfolds.”

Increasingly, words like “shift,” “adjust,” “recalibrate” and “reset” are being used to describe how buyers and sellers are trying to work in a market environment in which sellers and buyers are at odds over price and the public markets are openly hostile to deals.

“Buyer and seller expectations are still trying to recalibrate to the current market. In deals that don’t transact, buyers are being overly conservative, and sellers are being overly optimistic about asset values or the reality of the assets,” Nelson said.

The market remains replete with obstacles. Company executives want to remain in control rather than step away from businesses. In a down market, bid/ask spreads may widen while producers that are intent on a sale will face hurdles over their commodity mix and general price uncertainty, Cox said.

Cox expects to see more M&A in 2020 but said that transactions “could face headwinds and be delayed until the second half of 2020 [by] the coronavirus and market instability.”

“Any potential transactions will run into headwinds originating from coronavirus issues associated with reduced oil demand and lower commodity prices,” he said.

“Uncertainty, regardless of the source, [is] always a limiting factor in deal flow, which will need to work its way out of the market into 2020.”

by oil majors and independents further securing scalable positions. Photo by James L. Durbin.

Merger of equals

The color spectrum outside of Monahans, Texas, seems to narrow into bands of grays and browns that blend at the horizon. But the land in Monahans in March, pocked with mud puddles and holding up a few derricks under overcast skies, represents something new, at last, in the Delaware Basin of Texas—synergy.

In October, Parsley Energy Inc. announced it would purchase Jagged Peak Energy Inc. for $2.3 billion.

In the past two years, similar deals have resulted in upstream companies’ stock undergoing a public evisceration on Wall Street.

But Parsley’s deal and others that emerged in the fourth quarter of 2019 weren’t flogged.

The long campaign for consolidation has clearly won the hearts, and now the minds, of E&P executives and investors. The push E&Ps needed: the bottom of the market. E&Ps have performed worse than any other sector of the market over the past decade and represent less than 4% of the S&P 500 Index, an all-time low, according to Kimmeridge Energy Management Co. LLC.

have entirely

too many E&P

companies

with duplicated

overhead

infrastructure

and everything

else,” said Andrew

Dittmar, senior

M&A analyst at

Enverus.

“We really just have entirely too many E&P companies with duplicated overhead infrastructure and everything else,” said Andrew Dittmar, senior M&A analyst at Enverus.

But the particulars of how mergers are structured and paid will continue to be vitally important for successful mergers this year.

That lesson was made clear during and after Occidental’s bidding war to buy Anadarko. Chevron Corp. made an initial offer for Anadarko in April, offering $65 per share—a 39% premium on Anadarko’s stock price at the time.

Occidental countered at $76 per share, a staggering 62% premium on Anadarko’s market value.

Since announcing the deal, Occidental’s share price has taken a massive hit, and its value vaporized by $20 billion.

By contrast, successful deals in the latter half of 2019 centered on all-stock mergers offering low or no premiums between neighboring companies, Dittmar said.

“The playbook is pretty well-established from 2019,” he said, adding that companies also have to “lay out a very solid case on how does this accelerate the runway … how does this accelerate positive free cash flow?”

Merger of equals began to pick up momentum in late 2019, led by PDC Energy Inc.’s acquisition of SRC Energy Inc. in an all-stock merger worth about $1.7 billion, including debt. PDC paid no premium on SRC’s stock.

In contrast to other deals that have been whipsawed by market negativity in recent months, PDC stock rose 17% on the announcement.

Likewise, Parsley’s acquisition of Jagged Peak was an all-stock transaction that offered a 1.5% premium. Parsley was buffeted up and down by the market but otherwise didn’t appear to suffer directly from the deal.

Both the Parsley and PDC deals closed in January.

In cases where the premium didn’t sit right with investors, they rebelled.

The eventual merger between Callon Petroleum Co. and Carrizo Oil & Gas Inc. was stalled after Callon shareholder Paulson & Co. objected to the “unjustifiable” 25% premium the offer placed on Carrizo. A revamped proposal lowered Carrizo’s premium to roughly 7% and brought the deal’s final price down to $2.7 billion from $3.2 billion.

In a different test case, WPX Energy Inc. said on Dec. 16 it would purchase Denver’s Felix Energy II for $2.5 billion in a deal that was 64% stock. Dittmar said that after learning of the deal, he expected WPX’s stock to plummet like many other Permian Basin buyers.

Instead, WPX closed out the week nearly 12% higher.

WPX “showed you could go out and do a deal if the asset quality was high enough and the price was right,” he said. “And investors wouldn’t sell [a company’s stock] just because they saw the headline scroll across.”

managing

director for A&D

at Citi Global

Energy Group,

said his clients

are being more

cautious about

what they buy

while the typical

early year rush

to get to market

has decreased

significantly as

sellers hesitate.

The push by investors to reward operations with size and scale is historically tied to the premise that, combined, they deliver on total shareholder value, free cash flow and growth, Cox said.

“M&A is the pathway needed to consolidate companies, achieve efficiencies and eliminate G&A [general and administrative]” expense, Cox said.

“Consolidation will continue,” provided combinations feature low premiums, clearly defined strategic rationales, a clear-cut execution plan and operational efficiencies.

Opportunities also exist for private companies to buy other private E&Ps in roll-up transactions, particularly where private-equity sponsors have several companies in the same basin or area.

“While there have been discussions around this concept, roll-up sales may occur this year,” he said.

The headline grabbing deals of 2018 and 2019 will also lead to divestitures this year, particularly as strategic decisions are made on the focus of company portfolios, according to a February report on M&A by Deloitte.

Occidental’s Anadarko deal resulted in the sale of its newly acquired Africa assets for $8.8 billion. Occidental also entered into a $1.5 billion joint-venture agreement with Columbia’s Ecopetrol and is exploring a sale of its Utah assets.

“Increased rate of divestments to generate cash could go hand in hand with prioritizing projects in its expanded footprints in West Texas, Colorado and the Gulf of Mexico,” Deloitte said.

The potential hiccup is that companies are hunting for bargain basement prices that sellers simply cannot afford.

Fast and spurious

A mindboggling amount of money fueled the rise of the shale revolution. Since 2010, M&A has cost $567 billion, including about $140 billion coming from the Midland and Delaware basins, Enverus said.

That’s enough money to buy 43 of the U.S.’ most advanced aircraft carriers, plus tax, or fund the entire military budget of the U.K.—for each of the past 10 years.

Investors remain deeply skeptical of shale oil and gas, particularly upstream companies they view as debauched spendthrifts.

Already in a financial hole, investors are resistant to addition deals. Mark Viviano, head of public equities at Kimmeridge, sees little value in pursuing more.

“We don’t think the answer to the chronic over-investment within the industry is to put more capital at risk,” Viviano said. “The fundamental problem with a lot of these companies that are making acquisitions is they don’t have a premium valuation that can make it accretive. All they’re doing is amplifying the execution risk without a clear valuation arbitrage.”

To put a finer point on it, many deals haven’t led to greater returns for shareholders, which is often the pitch made to Wall Street, Viviano said.

“There’s just countless examples over the last few years where you’re not seeing the benefits of the acquisitions that were promised to investors,” he said. “There’s a reason that the market is skeptical and treating these companies the way that they are when they announce these deals. The value creation proposition is not clear.”

New inventory also amplifies execution risks, which have resulted in a number of companies “stumbling operationally coming out of deals.”

“We don’t think the answer is putting more capital into the business. It is taking capital out of the business and returning it to shareholders,” he said.

But rhythm of deal making in 2020 will likely take its cues from 2019 with fewer but higher-value transactions that hinge on PDP assets.

As U.S. shales continue to mature, a clear shift is underway toward corporate M&A and away from land deals. Last year was another step down, as asset transactions totaled about $25 billion—a 40% drop from 2018, Krasny said.

“Based on deal count, market velocity [for deals] collapsed by over 60% in 2019 year-over-year,” Krasny said. “We expect these conditions to continue in 2020 and could potentially see an even softer market.”

E&Ps appear reluctant, or at least pickier, as they shop for deals. The Permian remains the most attractive multibasin play, particularly as valuations have decreased and enhanced the potential to transact, Cox said.

Nelson said CIBC tries to help its clients as well as buyers see values and opportunities more realistically. But in basins such as the Delaware, comparable transactions, to some extent, have lost their meaning. “It’s a real challenge, and past transactions no longer serve as good indicators of current asset prices,” Nelson said. “Each deal and each asset is now being evaluated on its own merits.”

Krasny said he’s tuning into three M&A “frequencies” where he thinks the deals could keep coming.

In the Permian, transactions look to be driven by oil majors and independents further securing scalable positions. Despite the diversification of deals in other basins, Krasny said that the activity remains substantially centered there.

“Everything in M&A begins and ends in the Permian,” he said.

Thematically, however, corporate deals and consolidation via M&A remain important, if complicated by the market’s reluctance to fund deals.

“Single-well productivity is no longer the driver behind value creation and attention has switched to operational scale and efficiencies, pursuit of G&A and operational synergies and deployment of best practices across larger asset portfolios,” he said.

CIBC’s clients are generally interested in pursuing transactions, Nelson said. But as they weigh whether to take assets to market, they’re taking a more thoughtful approach to what is marketable now and how a transaction would help meet corporate objectives.

“Some groups are holding back and taking a wait-and-see approach to the market,” he said. Despite a souring of commodity prices, buyers are closely following where the bid/ask spread stands.

Cox said that his clients are also being more cautious about what they buy. The typical early year rush to get to market has decreased significantly, and sellers are largely waiting in the wings, he said.

“Sellers are willing to ‘soft shop’ the market, but they’re unwilling to run a process to avoid a potential failed deal,” he said. Instead of relying on sale processes, buyers and sellers are reaching out to “targets or buyers of choice to strategically pair companies.”

But deals are still missing one basic ingredient: capital.

Shelter in place

The fast money is gone from shale, racing like a jetliner’s shadow over landscapes and the half-scuttled fleets of drilling rigs, leaving E&Ps nowhere to hide. Capital is often given jaunty characteristics—patient, public, private, long or short—but it has forsaken the oil and gas world and taken on a new and surly identity: frustrated.

As 2019 ended, $16 billion in debt uncertainty hung over just 11 companies in the oil and gas industry.

By March, one of those companies, oilfield service provider Pioneer Energy Services Corp., filed for bankruptcy, prompting Eric Rosenthal, Fitch Ratings senior director, to offer a dire prognosis. As of early March, the default rate for high-yield energy debt during the past 12 months was about 10% compared to the overall rate of 3%. That rate, Rosenthal said, could hit 13% in 2020.

As the first quarter came to a close, pressure from debts, activist investors and souring commodity prices would seem to make the year ripe for distressed asset sales and further consolidation.

Large public companies are keen to reduce leverage and address reserved-base lending shortfalls by selling noncore assets, transactions advisers said.

But A&D doesn’t work without money, and the market and lenders have stubbornly tightened their money belts.

The A&D market that’s emerged is stressed, Cox said. An oversupply of sellers are faced with finicky buyers. Public companies in particular may prefer to shelter in place, eschewing land deals in favor of building operations into free-cash-flowing businesses.

Public companies are “highly reluctant to sell assets,” Cox said, particularly as they’re offered “reduced valuations when their cost of capital is lower than asset valuations being offered.”

As Krasny noted, when leverage levels rise above 3x debt to EBITDA, it becomes increasingly difficult to sell at a price that allows the owner to reduce leverage.

In the current market, valuations are driven less by price per acre and more by net asset value, Cox said.

The historical cycle of public-private asset deals is also out of sync.

“Private equity is looking to persevere by holding on for longer and recognizing the need for a more established production history that de-risks inventory,” he said.

Public companies are resistant to make purchases, since value is more and more difficult to show, even with economic, delineated inventory, Cox said.

Nelson said that public companies are looking to make strategic moves to divest noncore assets just as the bid/ask spread begins to narrow.

“More important to the climate for deals is capital availability, which we all know is brutally low and difficult to navigate for buyers,” Nelson said. “This is not only on the equity side but also with securing debt.”

Shifts in the M&A market that occurred in 2019 persist in 2020. Most of them, however, aren’t good.

“It’s a seemingly endless list of negative commentary around the market,” Nelson said.

sellers are still

adjusting their

expectations,

with transactions

stuck where

buyers are overly

conservative

or sellers too

optimistic

regarding asset

values, said Mark

Nelson, executive

director of A&D

at CIBC Griffis

& Small.

Public E&Ps sat out on the buy side. Private-equity funds seemingly came to terms with the reality of the new A&D market and pulled back, and their limited partnerships were less supportive of new fundraising efforts.

Commercial banks continued to tighten their underwriting standards for reserve-based lending.

Bankruptcies, too, seemed destined to continue marching on in 2020, which could further drag down transaction values, he said.

“The positive in all this … is an absolute lack of high-quality asset acquisition opportunities,” he said. “For our clients, it has created tremendous interest for their assets and given them the opportunity to transact with financially capable buyers are attractive values.”

A system-wide crash in capital availability is also possible. As capital markets keep up their resistance to providing E&Ps funding, Krasny said an expected contraction of the syndicated loan markets is unfolding. Loan syndication allows large amounts of money to be borrowed by breaking up the amount over groups of lenders to lessen exposure.

“The contraction is already underway,” Krasny said.

That also means that as E&Ps file for bankruptcy, banks are facing limited ways to recover senior secured debt.

“Profound disruptions in capital markets, from syndicated loans to bonds to equity, create headwinds to M&A, particularly, as prices continue to soften and leverage levels escalate,” he said. “These losses are likely to cause further contraction of the capital supply available to E&Ps, [which is] expected to result in further downward pressure on asset values. The degree of [that] is challenging to predict.”

And while potential defaults would seem like a leg up for buyers, it’s just another complication to deals, Krasny said.

“When equity markets are shut, bond markets are available only to a select few, and the bank market is increasingly poised for a pull back, asset monetizations emerge as a remaining source of accessing capital,” he said.

“Beyond certain levels of distress, the menu of strategic alternatives shrinks markedly and ultimate restructuring through bankruptcy remains the only alternative placing a firm into a state of ‘strategic paralysis’ until the ultimate restructuring takes place,” he said.

Bankruptcy sales require an investment of human and capital resources in order to walk away with a winning bid. The playbook for hunting for distressed assets is technical, complex and requires special expertise and stomach for particular kinds of risks.

“However, with the right team, capital and adviser, it could certainly be a potent and successful strategy.”

For the disciplined, well-capitalized buyers, however, the market offers an opportunity to hunt for the right asset at the right price. Buyers know the assets must sell in order to help keep the seller afloat, Cox said.

“Companies are thinking ahead regarding high-yield maturities and the need to get ahead of liquidity crunch,” he added.

Cox said that A&D could improve alongside the market across the next nine to 18 months.

“Asset sales can be impactful to companies undergoing financial issues, if material enough and divested early enough, to reduce leverage and help reposition the company,” he said. “Distressed asset sales will unfortunately continue. In recent months, several injured, challenged companies have been acquired at extremely low valuations compared to NAV [net asset value] and historical public valuation multiples.”

As 2020 speeds along, dealmakers offered a similar prediction for what would surprise them most this year: an A&D market returned to normal.

With fears rising of oil trade wars and a pandemic, the Delaware remains a prime spot. Photo By James L. Durbin.

SIDEBAR

| The Activism Bible |

|

Kimmeridge Energy Management Co. LLC is looking to put the E&P sector into a kind of business reform school. In a recent white paper, the activist firm said the U.S. E&P industry is in a time of crisis that has caused capital to flee the space. Kimmeridge, which agitated for PDC Energy Inc. to deliver sustainable cash flow prior to its merger with SRC Energy Inc., plans to persuade, cajole and, if necessary, fight to focus on equity underperformance in the public E&P space. In February, the firm said Mark Viviano would join the firm as head of public equities to lead the effort. Viviano will lead a team focused on public market investing within the energy sector. “The good thing about trying to be an activist in the sector is there’s no shortage of opportunities out there when you think about underperforming companies,” he said. “This is not about day one trying to go into proxy battles with a specific company. The idea is to own a concentrated portfolio of public energy equities where you think you have the ability to affect change.” Overall, Kimmeridge sees public E&Ps as enterprises that have suffered from mismanagement and held on to a production growth mindset long after the notion of oil and gas scarcity was played out. The firm largely sees E&Ps as companies that should seek to return capital to investors through sustainable dividends and share buybacks. “Change is really focused around capital allocation decisions and management incentives, and we think we’re uniquely positioned to launch a strategy that’s going to help reform the sector,” he said. Viviano said that activism is more about persuasion and winning over shareholders to better alternatives. With relationships spanning 15 years, he said he arguably has “as many battle scars as anyone else in the public energy sector. And that carries a certain degree of credibility when you’re talking about what needs to change within the industry.” Viviano said the firm is exploring different options to invest within the energy sector with an ace up its sleeve: experience on the buy side, sell side and in operations. “The key differentiator for Kimmeridge is having the in-house technical and geological expertise. That’s a big advantage that not many other activists in the space [have],” he said. Kimmeridge’s operational and technical team, based in Denver, gives the firm the ability to understand the assets and discuss with management teams what the assets are expected to deliver and how “we would be running them differently.” “There’s just a lot more credibility when you’re sitting down having those discussions as opposed to somebody who’s a generalist coming into the sector because they see an opportunity of a discounted valuation,” he said. Kimmeridge sees the path toward regaining investor trust as a series of to-dos for upstream companies with these necessary steps:

The firm also wants to compensate executives with less base pay and more equity ownership, with bonuses paid for absolute share price performance and payments that reward selling and consolidation. “We think in a mature sector like this where you can’t count on higher commodity prices in the future, those incentives need to change,” Viviano said. |

SIDEBAR

Deal Guide 2020

Over the past two years, it’s been something of an act of faith for companies to engage in transactions and brace for the moderate to severe backlash from Wall Street. Advisers seem to have divined at least part of what investors want to see.

Bruce Cox, managing director for A&D at Citi Global Energy Group, said a clear pathway to value creation is essential. Simply jamming two injured companies together without synergies can lead to negative reactions. However, jamming two healthily companies together with clear synergies has also proven unpopular.

However, combinations are generally favored because of the recognition that consolidation is needed.

“But, there is a lack of clean exit options for privates due to publics largely exiting as participating, active buyers,” Cox said.

However, successful mergers, in the eyes of the market, need to meet a Tinder profile worth of do’s and don’ts before investors will even consider them.

Cox said that in the current market, successful deals will:

• Maintain or improve corporate-level returns and visibility of free cash flow generation;

• Feature low to zero premiums in which value grows through a merger;

• Complement one another in the same basin or provide entry into superior basin;

• Offer solid production and enough cash to fund development;

• Maintain or improve the balance sheet;

• Generate superior inventory returns at current pricing; and

• Result in accretive growth.

Recommended Reading

Marketed: EnCore Permian Holdings 17 Asset Packages

2024-03-05 - EnCore Permian Holdings LP has retained EnergyNet for the sale of 17 asset packages available on EnergyNet's platform.

Elk Range Royalties Makes Entry in Appalachia with Three-state Deal

2024-03-28 - NGP-backed Elk Range Royalties signed its first deal for mineral and royalty interests in Appalachia, including locations in Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia.

Civitas, Prioritizing Permian, Jettisons Non-core Colorado Assets

2024-02-27 - After plowing nearly $7 billion into Permian Basin M&A last year, Civitas Resources is selling off non-core acreage from its legacy position in Colorado as part of a $300 million divestiture goal.

Analysts: Diamondback-Endeavor Deal Creates New Permian Super Independent

2024-02-12 - The tie-up between Diamondback Energy and Endeavor Energy—two of the Permian’s top oil producers—is expected to create a new “super-independent” E&P with a market value north of $50 billion.

Marketed: Foundation Energy 162 Well Package in Permian Basin

2024-04-12 - Foundation Energy Fund V-A has retained EnergyNet for the sale of a 162 Permian Basin opportunity well package in Eddy and Lea counties, New Mexico and Howard County, Texas.