A drilling rig is shown in the Permian Basin in Texas. (Source: GB Hart/Shutterstock.com)

The drive toward lower breakevens amid less-than-favorable oil prices could put shale operators on the road to vertical unbounded wells instead of cube developments in the Permian Basin until well economics improve, experts say.

The shift could put future productivity from adjacent zones at risk. However, experts at RS Energy Group (RSEG) say a closer look at the subsurface using electrofacies—which depict characteristics of rock intervals from petrophysical log data—can help pinpoint areas where there is less risk for hydraulic communication between zones.

An added benefit is that it is a visual exercise and a geology background is not necessarily needed to understand the petrophysics, according to Bryn Davies, a senior associate with the data intelligence firm that recently became part of Enverus.

“The electrofacies simplify all the log signatures into something more meaningful that you can tie to your general understanding,” Davies said, “and because it’s a very multi-disciplinary workflow, it really brings in concepts of engineering and data science as well. I think that regardless of your background, you can kind of take something away to better understand your basin and your acreage.”

The words were delivered as U.S. shale operators endure the latest downcycle brought on by lower, but slowly improving, oil prices and weaker demand due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. Companies have reduced activity and opted to shut in uneconomic wells.

RSEG believes today’s conditions will lead operators to prioritize top tier acreage and best benches, with no wells above or below, that deliver the lowest breakevens to survive through the year, Davies said. She highlighted a couple of pilots in which the firm’s geology models and data science teams used electrofacies to determine areas likely to have optimal EURs and areas where EURs could suffer.

Analysis revealed carbonate barriers can prevent across-zone communication.

In one pilot, she explained, a Wolfcamp A child bench was developed at 300 ft vertical spacing from the Wolfcamp B—where a parent well was drilled in 2017 at 1,800 lbs/ft and 47 bbl/ft. The child well was brought online about nine months later with a higher completion intensity. EURs for both parent and child were nearly half of what was forecasted. Results indicated a strong hydraulic communication between benches, she said.

Another pilot was carried out nearby using a similar completion design and spacing. The main difference, however, was the presence of more carbonate layers between benches. Neither the parent or child well suffered.

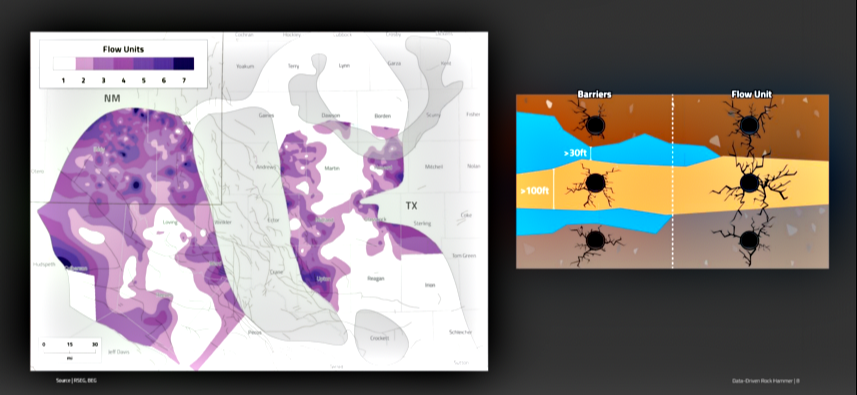

“We were able to do this using the electrofacies to flag 30 feet of continuous cemented carbonates where they separate a minimum hundred feet of reservoir, then mapped the number of flow units in the most targeted stratigraphy across both basins,” Davies said. “Where there’s a high number of flow units, the dark purples, there are more barriers between benches. Therefore, less risk to cross zone communication. While the areas where no barriers are present, the white areas, we see this is one continuous flow unit and high risk for future parent-child degradation if single zone development is prioritized.”

It also helps to know the basin, examining updated maps and other materials before beginning geological workflows, given perspectives may change as new wells are drilled, according to Graham Bain, also a senior associate with RSEG.

In addition, knowledge of carbonate deposition and distribution can help identify anomalies in future workflows. That way errors can either be singled out and fixed, or outliers can be explained.

As part of the workflow process, Bain explained that publicly available data such as wireline logs are gathered and the dataset is cleaned.

“We can use that data to create our electrofacies and determine the number of clusters we would like to use for evaluation. The electrofacies are made using a K-means clustering algorithm, which cluster unique associations from the triple combo curves: gamma density porosity, neutron porosity and resistivity,” Bain said. “The number of clusters we choose really depends on how granular we need to get. Are we looking to identify major lithology breaks such as carbonate, silica and shale?”

The firm’s study also examined fracability using an index that determines how easily rock fractures and where are fractures likely to stay open among other geomechanical properties. The index also comprised information from use of Poisson’s Ratio, Young’s Modulus and Shear Modulus along with Rickman’s Brittleness, fracture toughness and strain energy release rate, according to RSEG.

“The main purpose of using fracability in this study was to help solidify our understanding of potential fracture barriers,” Bain said.

To determine which facies acted as a flow barrier, each was correlated to other properties for classification using lithology, porosity and fracability.

“From our analysis, we generally get a sense that a minimum of 30 feet of carbonate is required to create a flow barrier,” he said.

He later noted, however, results can change depending on methodology used and techniques can be refined. Regardless, understanding the play at basin scale is key to knowing what lithologies to expect in different areas.

“This [clean] analytics-ready data feeds the electrofacies, which leverages the power of data science to cluster like log signatures and provide an effective tool that can be correlated to lithology, fracability and other data to help define the facies these cluster groups represents,” Bain said.

“You can use the electrofacies to identify flow barriers where you can define your own cutoffs, change them quickly to adapt to differences that you’re seeing on a local or regional level,” he added. “So, it really is a choose your own adventure type of workflow in identifying these flow barriers.”

Recommended Reading

Baker Hughes Marks Hydrogen Milestones

2024-01-29 - The energy technology company is involved with several hydrogen projects as it works to accelerate the hydrogen economy.

Braya Renewable Fuels Begins Commercial Operations at Revamped Refinery

2024-02-23 - The Come By Chance refinery in Newfoundland and Labrador produces renewable diesel instead of petroleum diesel.

Shell Taps Bloom Energy’s SOEC Technology for Clean Hydrogen Projects

2024-03-07 - Shell and Bloom Energy’s partnership will investigate decarbonization solutions with the goal of developing large-scale, solid oxide electrolyzer systems for use at Shell’s assets.

Stonepeak Joins Shizen to Form Asian Onshore Wind Platform

2024-03-26 - Stonepeak will have an 80% interest in the onshore wind energy platform, with Japan-based Shizen retaining the remaining 20% interest.

Bill Gates: ‘A Heroic Effort’ is Beginning, but Climate Goals Still Won’t be Hit

2024-03-26 - Bill Gates said during CERAWeek by S&P Global that the energy transition was picking up speed but still wouldn’t be able to achieve the climate goals established under the Paris Agreement of 2015.