[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the March 2020 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

More than the luck o’ the Irish may be at play to explain the extended success of Lario Oil & Gas Co., a private E&P nearing 100 years old—never merged, never acquired and still owned by the O’Shaughnessy family. Through the Depression, World War II, the 1980s downturn, the crashes of 1998 and 2014, plus the advent of shale plays that demand more capital than vertical drilling, Lario has stood fast.

While drilling at home and abroad, Lario has bought and sold production as the situation dictated. Legacy vertical wells in western Kansas, Oklahoma and nonoperated horizontal assets in the Bakken Shale now help fund its current focus, which is the Midland Basin’s Wolfcamp and Spraberry formations. But what’s the secret to this E&P’s staying power?

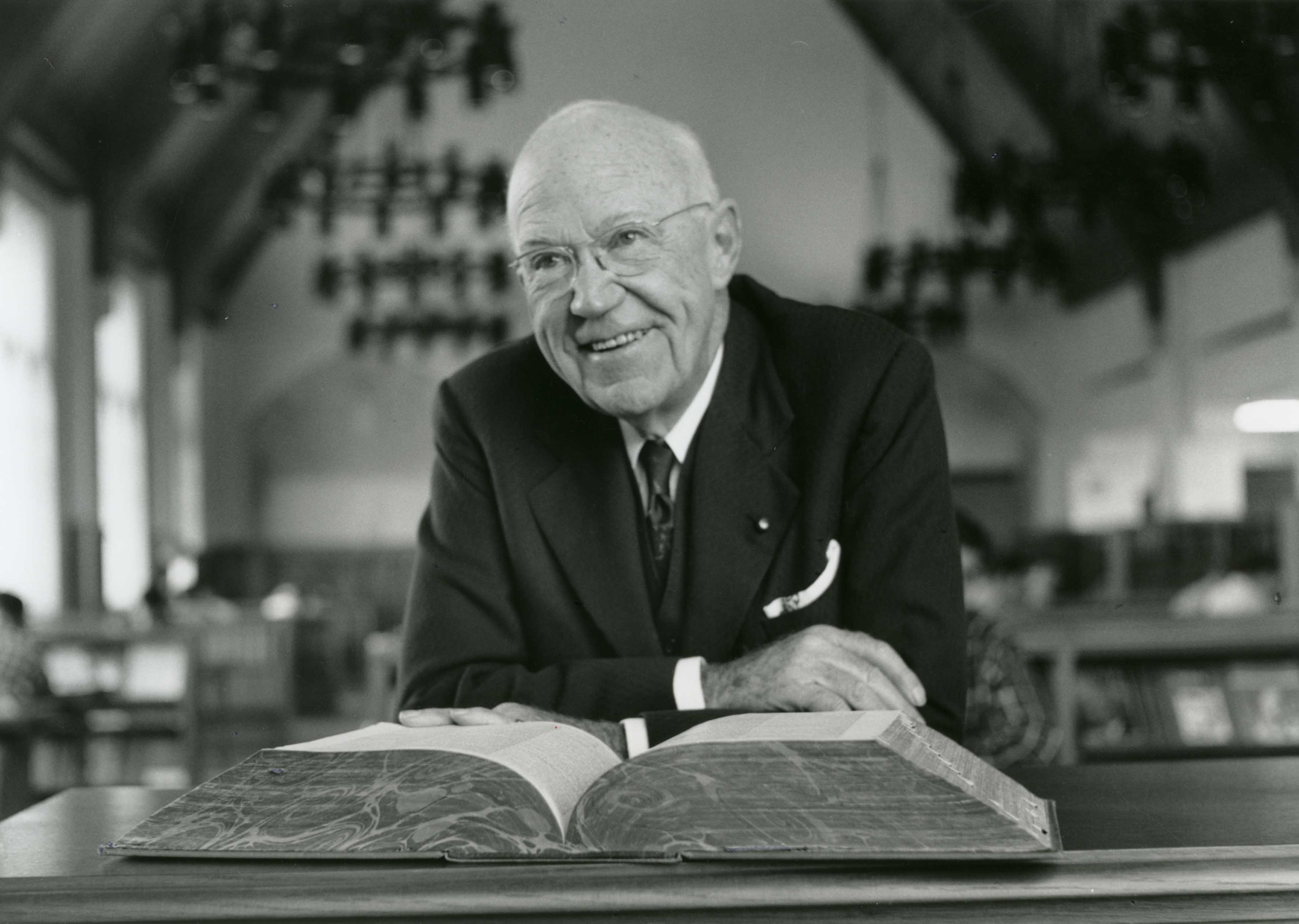

“We found ourselves looking in the rearview mirror and found that in every decade, we had significant discoveries that got us through the tough times. When you’re an almost-100-year-old company, you’d better have some nice discoveries along the way,” said current chairman and CEO, Mike O’Shaughnessy, grandson of the founder, known as I.A. (for Ignatius Aloysius) O’Shaughnessy.

The original business dates to 1917 when I.A., the patriarch, formed and built a small refining company in Blackwell, Okla., called Globe Refining Co., and later acquired a second one in Lamont, Ill., and then built one in McPherson, Kan. He was the youngest of 13 children of Irish immigrants; his father was a bootmaker for the lumberjacks during the golden age of lumbering in St. Croix, Minn.

After attending St. Thomas College in St. Paul, Minn., selling insurance in Texas and working for the Gates Rubber Co. in Denver, among other jobs, I.A. entered the refining business in 1917, eventually becoming one of the largest independent refiners in the U.S. But by 1927, he decided he needed to start an E&P company as well in order to get more oil as feedstock.

“The name came from I.A.’s son, Lawrence (Larry). Lari-o, for Larry O’Shaughnessy. People wonder about the name, thinking it means something exotic, but it’s just named for my Uncle Larry who was a child at the time,” Mike explained.

By the decades, Lario continued to expand. In the late 1920s, it was in Kansas, where it made its first discovery in Sumner County, followed by the discovery of the Ritz-Canton oil field a few years later. In the late 1940s, Lario moved into the Permian Basin when Mike’s father, Don, opened the Midland, Texas, office.

Also in that decade, I.A. joined a small group of independents that formed the American Independent Oil Co., which included Phillips, Ashland Oil Co., Deep Rock Oil, Sunray, J.S. Abercrombie and Ralph E. Davis (formerly with Standard Oil), to explore in the “Neutral Zone” lying between Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, acquiring a 6.25% interest in the concession. The forerunner of Getty Oil Co. (Pacific Western Oil Co.) bought it out later.

O’Shaughnessy admits that each generation believes they have big shoes to fill, not least of which because of his grandfather’s patriotism during WWII. Globe Refining saw some of its greatest growth during the war due to the accelerated demand for fuel by the military. Many jobs were created while Globe supplied oil to the U.S. Navy, and Globe invented some new refining processes for high octane fuel as well. I.A. also served on the National Refining Board as part of the war effort and in a newspaper article of the day, I.A. was quoted saying, “The hell with profits, we’ve got a war to win.”

In the 1950s after all the refineries were sold, Lario was operating leases in the Goldsmith-Blakeney Clearfork Unit in Ector County and in various other West Texas fields in Scurry, Martin and Crane counties. “That long-term production helped us grow during the ’50s and ’60s,” Mike said.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Lario went into western Canada and then the U.S. Rockies. Lario became one of the more active operators in the Minnelusa Trend and held that position until selling to the True Companies and Helis Oil and Gas Co. in 2010. Lario also exited Canada over a three-year period between 2010 and 2012.

During the 1980s, O’Shaughnessy started buying minerals throughout North Dakota, but the assets in Mountrail County were never leased until 2006 when the Bakken play was getting underway. “We had participated in the Elm Coulee Bakken development in Montana, and so we knew the Bakken could be incredible. I flew to North Dakota and found EOG [Resources Inc.] and Whiting [Petroleum Corp.] had leased up most of the county, so we brought in as many brokers as we could and leased around 75,000 net acres in Mountrail and offsetting counties.” Today the company’s most active partner in the Bakken is the Slawson Cos. Inc., another legacy family oil company dating from 1957 in Wichita, Kan., where Lario got its start.

Building and selling assets played a big role in the company’s history, all developed by exploratory drilling. “It was all wildcatting then, but in the 1990s when wildcatting was getting tougher and oil prices were lean, we made a concerted effort to start buying PDP instead of drilling. It seems most of our growth has come during the downturns. There’s always opportunity—when people are running for the exits,” Mike said.

The current E&P, which is based in Denver and Wichita, Kan., with field offices elsewhere and a big presence in Midland, is headed by O’Shaughnessy, who grew up in Midland and joined the company in 1977 after stints at Tenneco and some independents.

In turn, his oldest son, Ryan, joined the company in 2014 and is president. The latter began his career at Deutsche Bank in the energy sector and then spent 12 years working for investment banker and analyst Tom Petrie; he then served with the Agee family-owned company, Wapiti Oil & Gas LLC, in Houston, so he was very familiar with A&D tactics and energy financing. In 2014, Mike and his immediate family bought out most of the remaining family’s interest in Lario, with Ryan able to complete the deal through his banking connections.

“We have a rich family history in the company, so I guess we’ll have to wait a while to see if that continues into the fifth generation, as my oldest of 16 grandchildren is only 11,” Mike said.

Through the years, the company has learned how to operate wildcat drilling, conduct waterfloods in Wyoming and Kansas, go horizontal, and partner with key figures in the Bakken. Now it’s applying those horizontal lessons in the Midland Basin.

Learning quickly from mistakes has been one of the hallmarks that keeps Lario going, Mike said. “Now we like to say, ‘Fail fast; learn faster.’ No one wants to fail, but it seems our best lessons come from it and provide the impetus for growth and change.

“If you’ve got some long-term plans and long-lasting properties, you can take advantage of great opportunities. It used to be you held things from cradle to grave, but that’s changed,” Mike said. “We’ve often given up good long-term assets for buying even better assets. It’s important to be opportunistic, but you’ve got to do your homework; don’t move on rumors or information from press releases or third parties. Prove it yourself. Avoid group-think and ask hard questions again and again.”

Relationships matter, Mike believes. “Being born and raised in Midland, I know what a small world the oil industry can be. Old friends and acquaintances often end up being your partner.”

Starting out in the oil patch by sand blasting in the Texaco Inc. tank farm east of Midland, during blazing West Texas summers, Mike moved on to tagging along with Lario’s company landman to the courthouses.

“Being inside an air-conditioned courthouse was a vast improvement over getting sunburnt every day, but I loved it all. I never wanted to do anything else,” he recalled. Summer oil internships followed while he worked toward a degree in petroleum land management at The University of Oklahoma.

Bright future in the Permian

Today, Lario has 87 full-time employees who manage the company’s operated production in West Texas, Kansas, Oklahoma and nonop assets in the Bakken Shale, partnering with operators such as Slawson, EOG, Equinor (formerly the assets of Brigham Oil & Gas) and Whiting Petroleum.

The learning curve in the Midland Basin is steep, as it’s quite different from the Bakken, Mike told Investor. Cash flow from its horizontal Bakken assets and legacy vertical Kansas wells helped fund Lario’s renewed focus on the Permian Basin in its early stages of drilling.

In 2017, it acquired 10,000 acres in Midland and Martin counties from private-equity-backed Trail Ridge Energy Partners II for $345 million, a significant bolt-on to some assets it had acquired there a few years earlier.

At one time Lario also had properties in the Delaware Basin, but it has exited its handful of blocks there, finding it was getting too expensive to build the acreage position it wanted, Mike said, adding the company never likes to overpay. Instead it is focused entirely on the Midland Basin where it had a larger position. Add several dozen additional large and small acquisitions, and its position there now totals around 20,000 acres.

Since the end of 2017 the company has been running two rigs and one frac crew in the Midland Basin to hike operated current production above 22,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day. Lario has over eight to 10 years of inventory at this two-rig pace. “We’ll be cash-flow positive by the summer of 2020,” said Mike.

Lario joins several hundred private companies operating throughout the greater Permian Basin, but unlike many of them, it is not backed by a private-equity fund. All along, this has been built from the ground up, funded by internal cash flow from legacy production and a few select private individuals. However, Mike said, it restructured its business model in the 2014 to 2015 downturn to be more like a private-equity-backed company when it began rebuilding its technical horizontal team.

Adaptability has been a hallmark of Lario’s endurance. At one time it left West Texas in favor of more Bakken activity once that shale play took off. But, needing more capital to satisfy its share of authorizations for expenditures, it decided in 2013 to sell a portion of its Niobrara Denver Julesburg Basin assets. In the data room, ConocoPhillips Co. expressed interest in acquiring 100% of those assets, so Lario struck a deal. With the proceeds, it decided to return to West Texas in a big way and did so via the Trail Ridge deal.

“Going back to the Permian as an operator meant hiring some of the best minds in the business,” Mike said. “Our new team was formed specifically to drill and complete horizontal wells, and it came from great companies like Noble Energy [Inc.], Pioneer [Natural Resources Co.], Halliburton [Co.], Chevron [Corp.], Enduring [Resources LLC] and Apache [Corp.]. We’ve drilled 86-plus horizontal wells so far.”

In 2020, Lario’s focus will be on Wolfcamp A, B and lower Spraberry benches. The company has drilled some of the deeper benches to hold acreage, Mike said, “and now we’re systematically drilling from the bottoms up. The company is extremely data-driven, which helps in all our facets of drilling, completing and operating.”

Mike’s son, Ryan, added: “As far as the question of well spacing in the Permian goes, the industry’s focus needs to be on development sequencing in addition to the distance between wells. Lario analyzed public and private, proprietary data to reach this conclusion.

“While there’s been a lot of attention paid to co-development and in some cases cube development, we have concerns that these development strategies are impacting well productivity. Our philosophy at this stage is to honor a bottoms-up process in a single bench, as we believe this maximizes well performance.”

There’s been some debate in the industry on whether the Permian will eventually be a play only for the majors. True? “No. Companies like us can also compete and be highly successful here,” Mike said.

“It’s challenging though, because the title is so busted up; it took us five years to acquire enough acreage in the core area to build out our drilling units. But, keep two or three rigs running in the Permian and you can build a nice business.

“I’ll take the Permian over any other basin any time, even the Bakken, much as I love the Bakken. I’ve never seen anything like it before. We believe our position is located in one of the most economic, multibench areas of the Midland Basin. We’ve built a position we love.”

If Mike were to boil it down to three things that have enabled Lario to be closing in on its 100th anniversary, it would be consistently good leadership, perseverance and optimism.

“My grandfather, I.A., was the dynamic founding entrepreneur, and we are still very much aware and in awe of the legacy he left us. My father, Don, and his brother, John, took the reins in the next generation. They were followed by my cousin Patrick, who was CEO before I took over, along with his brother, Gerry, who contributed great entrepreneurial ideas in the third generation. I am the beneficiary of their careful management and wise counsel.

“The business has changed greatly in the last 10 years and the same perseverance that got us through the tough times in past historical downturns is what provided the will to change from more of an exploratory business to today, a data-driven resource company.

“But I think the greatest characteristic of any successful company, especially in the energy industry, is optimism. You just can’t operate in this environment if you don’t believe that you can find solutions to the challenges, that you can adapt to the changes and that the future is bright. If I didn’t truly believe all that, I wouldn’t be here today. I have a lot of faith in the new generation of our company and am optimistic that we’ll be here well beyond that 100th anniversary. And it doesn’t hurt to count on a little Irish luck, too.”

SIDEBAR:

Hire Tall Men

In the early days of the U.S. oil industry, in the late 1920s and 1930s, it was common for E&P and refining companies to sponsor their own baseball and basketball teams, which would compete against regional oilfield teams and/or teams fronted by other industries. A forerunner of Lario Oil & Gas Co., Globe Refining Co., had its own basketball team, and apparently it was a good one, since its members participated in the historic 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

“My granddad I.A. loved sports,” said Lario CEO Mike O’Shaughnessy. Indeed I.A. O’Shaughnessy was a star offensive tackle at the College of St. Thomas in Minnesota, and at one time he worked for the Amateur Athletic Association. He graduated in 1907. Later when he became the largest independent refiner in the U.S., he formed the Globe Refiners basketball team out of McPherson, Kan., which eventually lost the AAU championship against the Universal Studios team from Hollywood by one point. Players from those two teams formed the 1936 U.S. Olympic team, which went to the Berlin Games.

Team USA won gold by defeating the Canadians. This was the first time that basketball became an official Olympic sport. It was also historic because Adolph Hitler refused to award medals to any of the winning teams if they had African American players—recall that African American track star Jesse Owens won several races in these Games, which enraged Hitler. So instead, the iconic James Naismith, who had invented basketball in 1891 in Springfield, Mass., presented the gold medal to Team USA. He wrote the original rule book and lived to see the game become an Olympic sport. In the end this was a far greater honor for the players.

Recommended Reading

Oil Dips as Demand Outlook Remains Uncertain

2024-02-20 - Oil prices fell on Feb. 20 with an uncertain outlook for global demand knocking value off crude futures contracts.

Imperial Expects TMX to Tighten Differentials, Raise Heavy Crude Prices

2024-02-06 - Imperial Oil expects the completion of the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion to tighten WCS and WTI light and heavy oil differentials and boost its access to more lucrative markets in 2024.

US Oil Stockpiles Surge as Prices Dip, Production Remains Elevated

2024-02-14 - EIA reported crude oil stocks increased by 12.8 MMbbl as February began, far outstripping expectations.

US Gulf Coast Heavy Crude Oil Prices Firm as Supplies Tighten

2024-04-10 - Pushing up heavy crude prices are falling oil exports from Mexico, the potential for resumption of sanctions on Venezuelan crude, the imminent startup of a Canadian pipeline and continued output cuts by OPEC+.

Oil Rises After OPEC+ Extends Output Cuts

2024-03-04 - Rising geopolitical tensions due to the Israel-Hamas conflict and Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping have supported oil prices in 2024, although concern about economic growth has weighed.