A silver lining resulting from the painful downturn: low prices have forced a spending austerity by producers, resulting in balance sheets a lot healthier than in the past. (Source: Hart Energy/Shutterstock.com)

HOUSTON—The current energy investing environment is “the worst we’ve seen in multiple decades,” according to KeyBanc Capital Markets analyst Leo Mariani, characterizing investor interest in oil and gas company equities.

Multiples of many E&P companies are below even where they were in the late 1990s—prior to the shale era—when they had an exploration model with a much higher risk than it is today, he said while providing an industry outlook at a breakfast hosted by KeyBanc at the 2020 NAPE Summit.

One headwind energy investors face is the constant narrative that oil demand growth is going to zero, he said. “We’re going negative at some point in the future, but I continue to strongly believe that is overblown.” Oil demand growth decline “is a multi-decade process and not something that happens abruptly in this new decade.”

Keybanc forecasts oil to average $58/bbl WTI over the course of 2020, though it might be a rocky road getting there, he said, not unlike 2019. Last year oil averaged $57, but with a nearly $20/bbl price swing, “there was tremendous volatility. I wouldn’t be surprised to see something like that play out again this year.”

Certainly, that scenario is already in play, as prices entering the year topped $60/bbl, and in a matter of weeks flopped to just below $50, pressured by demand fears related to the coronavirus outbreak in China.

Mariani said the Chinese pandemic was a wrench thrown into the equation. “Coronavirus is driving the bus right now. The world market was in a process of healing itself prior to the outbreak of coronavirus,” he said. “We started to see greenshoots and improvement on the demand side.”

But the epidemic wasn’t as impactful as many anticipated, he said. “I expect as the coronavirus blows over we will get a significant snap-back in demand. I’d not be surprised if we get back in the low $60s by the middle of the year.”

Oil price volatility through the year is more likely to come from geopolitical tensions in the Middle East, which are “as high as they’ve ever been since the Gulf War in the early ’90s. There are tons of barrels that are offline or at risk of potentially going offline.”

Mariani believes OPEC will play its part via production cuts to keep Brent crude prices in the $65 to $70 range to support member country budgets, but non-OPEC supply remains a wildcard. New projects in Canada, Guyana, Brazil and Norway could accelerate growth from a brief slowing in 2019, from 1.3 million barrels of oil equivalent per day (MMboe/d) to 1.45 MMboe/d.

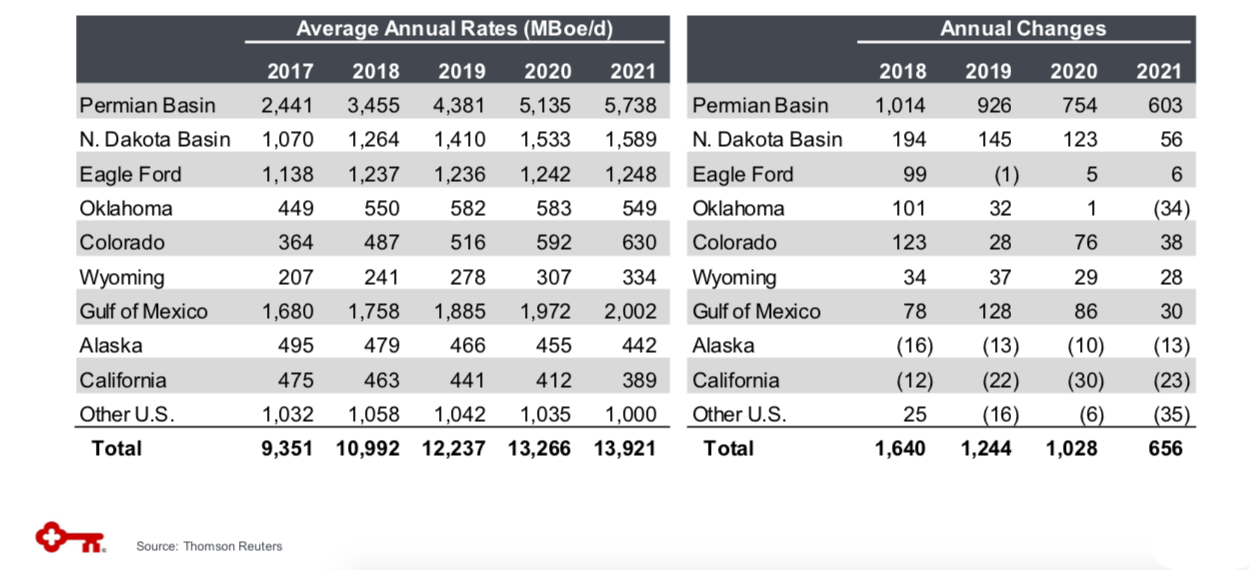

U.S. producers are not helping to slow growth, at least not yet, particularly in regards to Permian Basin production. Looking at large producers such as majors Exxon Mobil and Chevron Corp., and large independents EOG Resources Inc., Concho Resources Inc. and Pioneer Natural Resources Co., “we’re not seeing a sea change in the rate of growth and what they’re forecasting,” he said. “I think you’re seeing more of a soft landing in terms of U.S. oil production growth. I expect it to decline in 2020, but not at a draconian level.”

The optics for oil production growth improve in the back half of the year, he predicted, and global oil growth will fall below 1 MMboe/d. This “should lead to a healing in the oil markets,” he said.

Natural gas faces a tougher path to healing, however. “Unfortunately, it’s been a train wreck the past couple of years,” he said, resulting from “unbelievably high” production growth of 11% in 2018 and 9% in 2019. “When you couple that with a warm winter, that has absolutely crushed the market—and I don’t think we’re going to see a material recovery this year.”

KeyBanc projects natural gas prices to average $2.15/Mcf across the year, undercut by continued oversupply in the U.S. “for the next year or so.”

Mariani did offer that he sees an upside. “We’re at a price where a lot of these existing wells, particularly in mature basins like the Rockies and Midcon, they are simply not economic to produce. However you want to paint it, those prices don’t work for producers, so I think we will see shut-ins during the course of the year and next, which can certainly help balance things out a bit as we get into the second half.”

He also points to solid demand growth, which might slow “a bit” in the near term, but “it’s not going to go negative.” Eventually, he said, supply and demand “should work, and we should see prices go higher in a couple of years.”

A silver lining resulting from the painful downturn: low prices have forced a spending austerity by producers, resulting in balance sheets a lot healthier than in the past. This “has put a lot of these companies in much better shape to withstand lower commodity prices.”

Recommended Reading

Russia Orders Companies to Cut Oil Output to Meet OPEC+ Target

2024-03-25 - Russia plans to gradually ease the export cuts and focus on only reducing output.

BP Starts Oil Production at New Offshore Platform in Azerbaijan

2024-04-16 - Azeri Central East offshore platform is the seventh oil platform installed in the Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli field in the Caspian Sea.

Exxon’s Payara Hits 220,000 bbl/d Ceiling in Just Three Months

2024-02-05 - ExxonMobil Corp.’s third development offshore Guyana in the Stabroek Block — the Payara project— reached its nameplate production capacity of 220,000 bbl/d in January 2024, less than three months after commencing production and ahead of schedule.

What's Affecting Oil Prices This Week? (Feb. 5, 2024)

2024-02-05 - Stratas Advisors says the U.S.’ response (so far) to the recent attack on U.S. troops has been measured without direct confrontation of Iran, which reduces the possibility of oil flows being disrupted.

Tinker Associates CEO on Why US Won’t Lead on Oil, Gas

2024-02-13 - The U.S. will not lead crude oil and natural gas production as the shale curve flattens, Tinker Energy Associates CEO Scott Tinker told Hart Energy on the sidelines of NAPE in Houston.