Liberty Oilfield Services employee working a frac site last year in the Eagle Ford Shale. (Source: Tom Fox/Hart Energy)

[Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the January 2020 edition of E&P. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

With investor pressure sidelining ceramic and other fancy proppant and alternative carrier media like CO2 still but pipe dreams, sand and water will remain indispensable hydraulic fracturing ingredients for the foreseeable future. Those immediate futures, however, are on markedly different trajectories, with the former fretting over too many players and shaky demand prospects and the latter emerging as the newest darling of an otherwise tightfisted equity market.

Not surprisingly, the multizone Permian Basin remains the centerpiece of any evaluation of the supply- demand equation. The numbers speak volumes: Any analysis of U.S. frac sand consumption in 2020 estimates well over half the demand will be in the Permian’s Midland and Delaware basins; the Permian also accounts for $13.4 billion of the $37.5 billion that IHS Markit estimated to be spent on water management across the U.S. in 2019.

The sand and water combo have been among the biggest beneficiaries of the near-universal trend of longer laterals and multiple frac stages, with proppant loadings of 2,000 lb/ft to 2,500 lb/ft now seen as the optimum completions design. Recent completion programs by and large also incorporate fine-grain 100 mesh and 40/70 mesh sand, particularly in plays with in-basin capacity.

Corresponding with the switch to finer grain sand, modified frac fluid chemistry and assorted treatment technologies have enabled the wholesale push to recycle spent water, with some operators reporting 100% reuse. Consequently, sourcing fresh frac water represents a mere 5% of the total water management spend.

“We’ve changed the requirements for frac water, so the water doesn’t need to be completely clean. There are still some plays where they use a lot of freshwater, like in Oklahoma’s Stack and Scoop, but they use a lot of brackish water in Texas, which is a lot cheaper,” said Paola Perez Peña, an IHS Markit principal research analyst.

That leaves the gathering, treatment or disposal of flowback and produced water emerging as a midstream industry unto itself—one that is highly localized and among the few areas in the unconventional sector where the money is readily available.

“The water business is becoming more like a midstream infrastructure industry with a lot of capital being tossed about,” Perez Peña said. “With more localized infrastructure, operators are able to treat water and reduce costs. The entire process becomes more efficient. A lot of people see this as a solution to the whole water problem.”

Avoiding the use of freshwater in frac fluids is particularly crucial in the Permian’s arid and perpetually drought stricken home turf of West Texas and southeastern New Mexico, which until last summer had different rules governing prodigious produced water volumes. Laws enacted in both states clarify, in part, that operators own the water their wells produce and contractually can relinquish control to midstream companies for recycling.

Sand balancing act

The divergent trend lines projected for sand in 2020 reflect the intrinsic ambiguities and fluidity of operators’ spending and completions strategies, as activity going forward remains at the mercy of commodity prices and circumspect investors. Nevertheless, analysts agree a rebalancing of the supply-demand equilibrium is beginning to take shape.

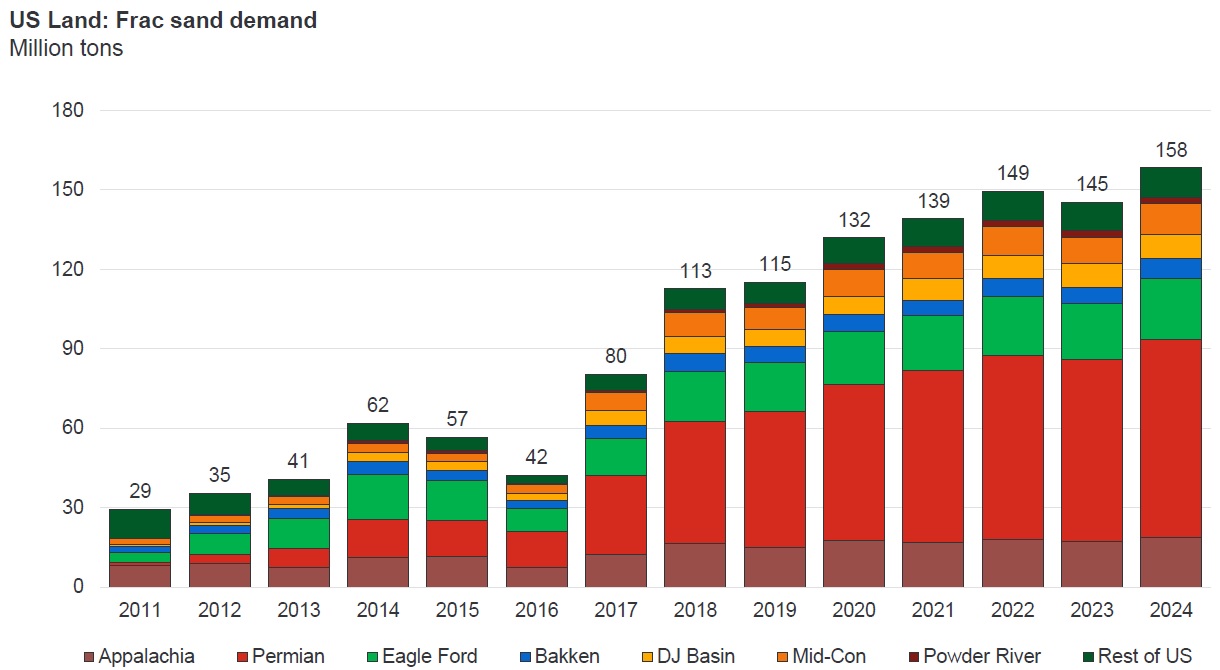

Rystad Energy sees cumulative sand demand increasing from 115 MMtons in 2019 to 132 MMtons in 2020. Rystad’s estimate is more bullish than that of Westwood Global Energy, which predicts U.S. frac sand consumption of 106 MMtons in 2020, up year over year from the estimated 94 MMtons pumped in 2019. The 2019 demand forecast parallels what Westwood estimates will be a 5% and 3% decline in drilling and completions, respectively (Figure 1).

Efforts to bring supply and demand into balance begins and ends in the Permian, where Hi-Crush Partners ignited the stampede to construct in-basin surface and subsurface sand mines some two years ago.

Expectations did not meet realities, and the Permian became oversaturated; at one point in 2019, prices dove to below $10/ton. About 22 active mines remained in the Permian in late 2019, but between five and seven of those were expected to either pull back production or possibly shut down.

“Prices crashed in West Texas but have held up rather decently in other basins, where there are not as many suppliers,” said Thomas Jacob, a Rystad senior analyst. “It’s not just the capacity; it’s the number of people holding that capacity. So with so many companies in that play, the supply is very fragmented.

“The Permian holds 73 million tons in nameplate capacity on paper, but some mines are being utilized at 50% to 60% of capacity. If they had to increase production suddenly, it would take time to increase shifts and eliminate inefficiencies in the supply chain, so the effective supply would be about 80% to 90% of that 73 million nameplate capacity.”

The 13% increased demand Westwood forecasts in the Lower 48 in 2020 falls short of growth expectations but is partly offset with a nationwide supply pullback from 140 MMtons in 2019 to 112 MMtons in 2020.

“In talking with many of the mine owners, you have various strategies being used right now, but obviously they’re kind of pulling back the production of sand, especially in the Permian,” said Todd Bush, Westwood head of NAM and unconventionals. “They’re trying to get closer to the supply-demand balance toward the end of [2019], but that could extend into the first half of 2020.”

After closing one of its three Permian mines, Black Mountain Sand, for one, opened two mines in the Eagle Ford in 2019 and another in Blaine County, Okla., its first outside of Texas. Annual production from the five active facilities totals 16.3 MMtons, with all but 6.3 MMtons coming out of the two operational West Texas mines.

“For the overall market, we see demand increasing over the long term and very little new supply of sand or last mile services being added to the market,” said Bob Rasmus, CEO of Hi-Crush, which expected to sell between 2.4 MMtons and 2.7 MMtons in the third quarter of 2019, compared to second-quarter deliveries of 2.7 MMtons.

After ramping up capacity at its Kosse, Texas, mine earlier in 2019, U.S. Silica Holdings in November closed mines in Tyler, Texas, and Utica, Ill., citing the declining outlook in completion activity. “Energy markets deteriorated further and faster than expected during the [third] quarter as E&P budget exhaustion slowed completion activity, resulting in lower demand and pricing pressure,” President and CEO Bryan Shinn told investors on Oct. 30.

Meanwhile, truckers naturally followed miners into the Permian and quickly found themselves surrounded by too many trucks and too little to haul. “We heard of several trucking companies that have actually pulled out of the Permian because the pricing and competition are so fierce that many were not making margins,” Westwood’s Bush said.

Plans to expand in-basin mines beyond the Permian, Eagle Ford, Oklahoma and the Haynesville have been stymied by low-quality sand reserves, insufficient activity to justify the investment or stifling permitting requirements. The regulatory climate is particularly chancy in the contentious Colorado core of the Niobrara-Codell play in the Rockies’ Denver-Julesburg (D-J) Basin.

“We currently have plans for expansion, but the process of permits and exploration takes a while,” said Allison Donahue, Black Mountain’s brand manager. “We’ve announced our intent to expand into the D-J Basin, but it’s going to take a little time.”

Owing to their proximity to Upper Midwest mines, operators in the Appalachia Basin’s Marcellus and Utica plays, the D-J Basin and the Bakken rely mostly on the once-dominant Northern White sand. Along with direct rail access, plays like the naturally fractured Bakken require comparatively low proppant loadings per well, making in-basin mines impractical.

“The Bakken has sand reserves, and some are of sufficient quality, but they don’t use a lot of frac sand from a completions intensity perspective, so the incentive’s not there,” Rystad’s Jacob said. “The Appalachia also has sand reserves, but the quality is really poor.”

The stress factor

Northern White sand, which held roughly three-fourths of the U.S. proppant market in 2014, was prized primarily for higher crush strengths than the Texas sand typically recovered either from dunes or the Hickory and similarly sand-prone formations. Owing to tightening economic margins and rail transport from mines in Wisconsin, Minnesota, Missouri and elsewhere representing nearly half of total sand costs, Permian operators rely primarily on homegrown reserves. Based on IP rates, finer-grain in-basin sand is seen as sufficient and, from a logistical perspective, makes for a more cost-effective option, even in the higher stresses intrinsic to the Delaware Basin.

“The Delaware has deeper formations with higher closing pressure, but when we actually look at the IP30 and IP60 day rates and how that’s trended over time for the past two years when in-basin sand started being used, we haven’t seen a change in the data,” Jacobs said.

Northern White sand miners concede that competing with local proppant is a taxing proposition. “I think with the economics of Northern White sand versus local, it remains a very compelling proposition for the operators there [Permian] to be trying the local sand,” Covia Corp. CFO Andrew Eich told analysts in an August 2019 earnings call. “Even if they moved back to Northern White, I think it’s a little early for there to

be a broad swing.”

Westwood’s Bush said that while some of the larger Permian operators are still using Northern White, local demand will likely remain flat.

“One thing we’re watching pretty closely is some of the trainload activity in the southern New Mexico area. Some Delaware Basin operators are still shipping from Wisconsin, but from a demand perspective, we see it probably remaining flat. The operators are looking at how they can reduce costs, either through sand or last-mile logistics,” he said.

To the immediate east, lower-quality sand in the South Texas Eagle Ford presents an opportunity for importers.

“We certainly are hearing increasing chatter in the Eagle Ford that the local sand quality is significantly worse than Northern White in terms of performance,” Eich said. “I think that’s probably the first basin where you see a broad shift back to Northern White.”

Jacobs said a comparative analysis of treatment pressures seems to bear that out. Some 95% of the treatment pressures in the Midland Basin fell below 8,000 psi, making it well-suited for in-basin sand. Conversely, of the completions examined in the Delaware and Eagle Ford, 70% and 60%, respectively, averaged about 8,000- psi treatment pressures.

“We actually looked at the average treatment pressures of every well in the Delaware, Midland and Eagle Ford. While the Delaware and Eagle Ford are similar in average treatment pressure, Eagle Ford in-basin sand is not of the same quality as that in the Permian. The crush strength is much lower,” he said. “We’ve heard that some [Eagle Ford] operators have used in-basin sand and shifted back, while some use in-basin sand and are happy with it. The dust hasn’t settled yet, so it’s too early to make any definitive conclusions.”

As much as appeasement of returns-focused investors helped decimate the demand for premium ceramic proppant, the high-strength, resin-coated sand sector faces a similarly tough slog. Black Mountain discovered as much in August after forming a partnership with Hexion Inc. to offer in-basin, resin-coated proppant, using the company’s Voyager mobile resin-coating service.

“Resin-coating has some proven benefits, but we do not see a really large demand yet,” said Black Mountain’s Donahue. “We like to provide the option to our customers because it is really efficient and economical to make.”

A Hexion spokesman said the mobile unit remains on station at one of Black Mountain’s Permian Basin mines.

Sidestepping pumpers

The once typical model of bundling all stimulation services under usually integrated pressure pumping companies has been largely upended, as sand providers sell directly to operators. Self-sourcing took hold in the Permian, where the multitude of local mines gave operators a competitive edge, but it has since expanded elsewhere and, in the process, increased the logistical pressures on proppant providers.

“Obviously, some E&Ps have long-standing relationships with pressure pumpers and they’ll continue to rely on them, but others are going directly to the mine companies,” Bush said. “You can see some significant savings on the costs of sand and sand delivery.”

At mid-year 2019, Hi-Crush said direct sales to operators increased to a record 66% of the overall tonnage delivered, more than double the 31% sold directly during the second quarter of 2018. U.S. Silica, for another example, pointed to recent direct-sale contracts as signs of a continuing and welcomed trend.

“My experience is that energy companies have much better visibility as to what they’re going to use in terms of proppant as opposed to the service companies that obviously move around a lot and work for different energy companies,” U.S. Silica’s Shinn said.

As much as direct purchasing reduces costs for operators, it increases the last-mile pressures on sand companies, leaving single-source providers at a decidedly competitive disadvantage. “As more E&P companies begin direct sourcing, there’ll be additional requirements put on a provider’s logistics team to make sure sand gets to the well site,” Bush said. “They’ll have to coordinate all activity, so there’s no downtime.”

Hi-Crush and U.S. Silica are among the integrated sand companies that provide distinct logistics networks, complemented by digital and automated platforms, to better track inventories and deliveries. Covia, however, believes the plethora of players in the logistics arena makes it more economically prudent to team up with specialized last-mile providers.

“We continue to believe that the market is fully saturated and potentially oversupplied, and the prices and margins will come down for that solution,” said Richard Navarre, Covia’s president and CEO. “And the technology continues to change, which requires continuous capital investment in that market. We’ve taken the asset and capital-light approach and partnering with last-mile providers, so we can still provide for our customers that want a last-mile solution.”

Monetizing water

Meanwhile, transactions over the past year reflect the growing trend among operators to liquidate water assets and, in turn, team up with localized third-party water management companies to cut costs.

“Right now the market is so hot, and the valuation of that water is very high,” said IHS Markit’s Perez Peña. “The capital is not going to stop coming in, at least for the next couple of years. The perception is very positive.”

To point, Continental Resources netted $85 million on July 31, 2019, for a “small portion” of what it values as a $1 billion ater gathering and recycling network across Oklahoma and North Dakota. The sale and associated long term water management arrangement with Oklahoma-based Lagoon Water Solutions encompasses Continental’s infrastructure in Blaine County, Okla., which serves its Stack asset. The deal gives two-year-old Lagoon the largest such system in Oklahoma and will make it the state’s first midstream company to provide recycled water for completions. Complementing its 30,000-bbl/d recycling capacity, Lagoon also holds 200 miles of pipe and 17 saltwater disposal (SWD) wells with a cumulative 310,000-bbl/d capacity.

Prior to an Oct. 8 Bloomberg report to the contrary, Continental CEO Harold Hamm shrugged off questions that the entirety of the two-state water network is for sale. “This is a very valuable asset, and if we ever did anything in near-term, it would probably be a small stake, but there is nothing grooming or contemplated right now,” he told analysts on Aug. 6.

Also in Oklahoma, Marathon Oil Co. signed a 15-year water gathering and disposal agreement with local water management company Bison, which claims the only infrastructure dedicated exclusively to the Scoop and

Stack plays.

Elsewhere, Concho Resources forged a long-term water management agreement with Solaris Water Midstream LLC on July 31 that takes in some 1.6 million acres in the northern Delaware Basin. Solaris paid an undisclosed sum for 13 SWD wells and roughly 40 miles of largediameter pipeline, which the midstream company integrated into its Pecos Star pipeline network. At the time of the agreement, Solaris held more than 300 miles of largely 16-in. water gathering pipelines and over 500,000 bbl/d of recycling, disposal and storage capacity.

The joint venture, taking in New Mexico’s Eddy and Lee counties and extending into Reeves and Culberson counties in West Texas, came on the heels of an earlier 16-MMbbl recycling contract that Solaris signed with Concho.

Concho signed a similar sale and management agreement with high-rolling WaterBridge Resources LLC in January 2019 for its produced water assets in the southern Delaware Basin of Reeves, Pecos and Ward counties in Texas. Armed with $800 million in debt facilities, WaterBridge, in separate transactions in December 2018, also snapped up the Texas Permian water assets of Halcón Resources and NGL Energy Partners.

H2O Midstream acquired the Howard County, Texas, water assets of Sabalo Energy LLC on Aug. 21, concurrent with a 15-year water gathering, disposal and recycling services agreement.

More water assets could soon come on the block. Callon Petroleum hinted its pending acquisition of Carrizo Oil & Gas could put the combined Permian Basin and Eagle Ford water network up for sale. “We’re not in the water business, but we do have an investment that we think there’s significant value to unlock,” Callon President and CEO Joe Gatto told analysts in an Aug. 8 call.

It’s the same for Pioneer Natural Resources’ Permian-centered water management entity. “We’re evaluating it

now and the board will make a decision in 2020,” said Pioneer President and CEO Scott Sheffield.

Perennial expansion

Solaris Water, for its part, is engaged in what its principals characterize as a continuous expansion required to handle the tremendous volumes of flowback and produced water generated in the Delaware Basin. The midstream company, which participated in developing the New Mexico produced water ownership and transportation legislation that took effect in July, plans to have at least five recycling facilities up and running by mid-2020.

The company moved closer to that target in late October with the startup of the Bronco produced water recycling and blending center in Lee County, N.M., which has 130,000 bbl/d of maximum throughput capacity. The development of the Bronco facility followed the completion of the Lobo Ranch recycling and blending facility in Eddy County, N.M., with maximum capacity of 240,000 bbl/d, said Amanda Brock, Solaris Midstream’s COO and chief commercial officer.

Solaris Water’s integrated Pecos Star System, which traverses Lee and Eddy counties, likewise is in a continual expansion mode and was expected to stretch more than 330 miles by year-end 2019.

“We originally said we would have Phase 1, Phase 2 and Phase 3 expansion plans. Now, it seems we’re on Phase 15, so it’s really just been a matter of continual expansion,” Solaris CEO Bill Zartler said.

With the combination of flowback and the notoriously high water cut in the Delaware Basin throwing the water-oil ratio out of whack, gathering systems face tremendous pressure to move as much as five times more water than oil. Attesting to the increased volumes being pushed through the network, Brock said pipe larger than the typical 16-in. is being considered, as authorized under right-of-way agreements.

“We are looking at increasing the size of our pipe as we look at laying a second pipe in the existing right of way. We hoped we were sizing our system appropriately, but with the rapid unprecedented growth we see in the Delaware Basin, we may not have sized our pipe large enough in certain areas and will have to expand our capacity faster than we thought to meet our customers’ needs,” she said. “We don’t use trucks and have no intention of using trucks.”

While operators have come to accept higher percentage blends of treated produced to brackish water for reuse, the quality of water entering the pipeline network must meet stringent contractual specifications.

“For the most part, water coming out of New Mexico aquifers is nonpotable, so it needs some treatment. We call that brackish water, and while we see anywhere from 50/50 to 90/10 blends on average, we’re close to 70/30 blended treated, produced water to brackish water,” Zartler said. “When we talk about brackish water, we’re really talking about any water that’s over 1,500 TDS to 2,000 TDS [total dissolved solids].”

During treatment, flowback and produced water are run through chemical and mechanical processes to reduce the levels of contaminants like iron and oil. The water is then run through a series of weir tanks and, after additional filtration, is sent to a pond or aboveground storage tank where, depending on the specifications, the treated water may be blended with nonpotable water.

While the quality of produced water in the Delaware is generally better than that of its sister sub-basin, Zartler said much of the disparity could be attributed to the maturity of the Midland Basin, where injection in SWD wells is more commonplace.

“It’s area-specific, but the water quality in the Midland Basin isn’t as good, so the treatment to get it to spec is a little more involved. I’m not sure the water coming out of the ground is any different, but a lot of it has to do with older surface equipment that is not separating the oil as well, and the oil is a bit heavier,” he said. “We’ve been recycling there for three years, but the Midland Basin is complicated by a large number of landowners, making it a bit more difficult to build larger integrated [gathering and recycling] systems.”

Throughout the Permian, a key enabler to reusing large volumes of produced water has been the transition from gels to slickwater fracs that entail heavy loadings of finer grain sand.

“If you look back three to four years, operators needed gelling agents to thicken up the frac fluid so it could carry larger grains of sand into the reservoir. Today, with the use of sand with a finer grain, they don’t need as much viscosity, so they can carry massive amounts of sand much farther using lower quality water enhanced with additives like friction reducers that work very well with saltwater,” Zartler said.

Disposal capacity issues

In plays where flowback and produced water streams are either too dirty to economically treat and reuse or those where activity levels, prices and low water cuts are insufficient to justify largescale treatment facilities, SWD wells remain the only available alternative. However, injections are being hit on a number of fronts, primarily related to stringent regulations and capacity limitations.

Problems with SWD wells have long been on display in Oklahoma where injections into the deep Arbuckle Formation have been blamed for what, until recently, was a spate of earthquakes. The state responded to induced seismicity events by forcing the closure of some wells and limiting injection rates in others, while seeking alternatives. A feasibility study commissioned by the state-sanctioned Produced Water Working Group (PWWG) recently examined, for instance, new iterations of evaporation technologies to either reuse produced water or increase the capacity of disposal wells. One of the conclusions of the report released in August 2019 found that “enhanced evaporation allows excess produced water to be dealt with when reuse and disposal are already at their practical limits.”

Seismic jitters also extend to the Permian, but future injection capacity is a primary issue.

“The concern there is with the disposal capacity,” said IHS Markit’s Perez Peña. “We see the Midland [Basin] having enough capacity for the next three years, but if they continue to produce as much water as they do right now, it’s going to be a big issue.”

The Railroad Commission of Texas, the state’s chief oil and gas regulator, issued 540 injection well permits for the core Permian districts between Jan. 1 and Oct. 1, 2019, compared to 527 similar authorizations for the same period in 2018. “The Railroad Commission is working on more regulations for injection rates, so [in 2020] we may see a delay in getting those permits approved,” she said.

A dearth of approved and compatible disposal receptacles is particularly glaring across the Marcellus and Utica fairways of Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Ohio in the gas-rich Appalachia Basin, where low prices also inhibit the widespread construction of large-scale treatment facilities. Antero Resources’ $275 million Clearwater treatment facility in West Virginia fell victim to doggedly low gas prices in September when it was temporarily idled for an economic reevaluation after only two years of operation. Antero has not responded to requests for comment on when a decision on the future of the plant may be forthcoming, but the company suggested in late October the closure could be permanent.

“By transitioning our operations to localized blending and reuse starting in August and shifting away from the Antero Clearwater Facility in September, as the facility was idled, we were able to drive down our LOE [lease operating expense] substantially,” CEO Paul Rady said in an Oct. 30 conference call. Conversely, restrictive disposal regulations, especially in Pennsylvania, force many operators to truck produced water to Ohio where permitting disposal wells is less daunting.

“There’s a huge lack of disposal capacity in the Appalachia Basin because of the strict regulations, so operators are paying premium trucking fees,” Perez Peña said. “They are trying to build some pipelines, but there are no clear regulations in place for moving produced water. I think you’ll see more pipelines coming into the Marcellus but only when gas prices get better.”

Tight restrictions on sourcing water from streams and rivers likewise force many Appalachia operators to truck freshwater to well sites. Replicating a practice common to portions of the Permian and elsewhere, an operator in West Virginia, however, managed to secure a permit to source groundwater adjacent to a two-pad development. The operator contracted Emery & Garrett Groundwater Investigations, a New Hampshire-based groundwater exploration and development company, which after locating a more than 500,000-gal/d water reservoir within a fractured bedrock, recently drilled two 8-in. water production wells.

Contaminants pose yet another obstacle

“In the Appalachian Basin, the supply of freshwater is relatively plentiful. But the TDS levels are very high and NORM [naturally occurring radioactive materials] can be a problem as well for the produced water,” said Jared Ciferno, technology manager for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory in Morgantown, W.Va. “However, a lack of good deep-injection options in Pennsylvania means that many companies are using chemical additives to permit reuse of higher TDS flowback water for fracturing.”

Lower volumes, ample disposal capacity and less expensive trucking in the D-J, Powder River and Williston basins make injection a more cost-effective option, according to Perez Peña. “The water cut is low in newer Bakken wells, but we do see a big water cut in the older ones. It’s slightly higher than the D-J but certainly not on the scale of the Delaware,” she said.

While not part of the Oklahoma PWWG study, a Colorado company claims its take on evaporation technology can extend the life of SWD wells up to twentyfold while eliminating airborne salt pollutants. “We take care of the really nasty stuff that can’t be recycled. By hyper-concentrating the water, we can make disposal wells last about 20 times as long, because you’re putting a concentrate down the hole that won’t clog up the formation you’re injecting into,” Robert Ballantyne, R&D director of Resource West Inc. (RWI), said following a September demonstration for a major operator in Midland, Texas.

In what he described as enhanced evaporation with drift control technology, Ballantyne said the RWI system uses velocity and sedimentation control to squeeze contaminants into hydrated 100-μ droplets. The evaporation systems float on the impoundment pond, enabling the now-concentrated droplets to fall back into the water quickly. Like a number of evaporation systems still in use, Ballantyne said the genesis of the RWI technology could be traced to converted snowmakers which, like those adapted from common sprinkler systems, rely on extreme velocity to stream produced water over a holding pond. The high-velocity flow paths cause the droplets to dry out and shrink to as low as 5 μ, with the particulate matter going into the atmosphere as dry aerosol. These minute fragments, Ballantyne said, can float for miles before precipitating out and falling into the environment as sodium chloride, sodium sulfate, calcium chloride and equally noxious salts.

“We were using converted snowmaking machines, but saw their time in the oil field was coming to an end, as the water was getting saltier and saltier, and those machines were creating so many pollution problems by spraying saltwater everywhere,” he said of the three-year, $1.9-million development program that led to the current system. “With such highly contaminated water, we needed more control over the droplets.”

By never allowing the droplets to dry out, the system keeps ionic contaminants tightly concentrated, with controlled pre-injection deposition into the impoundment. “Concentrating the volume relieves the pressure on the disposal well. You’re still sending all the material you need to downhole, but you don’t need the pressures, and your saltwater disposal wells are not constantly under a pressure and relaxation cycle,” he said.

Read E&P's other January cover stories:

Recommended Reading

Eni, Vår Energi Wrap Up Acquisition of Neptune Energy Assets

2024-01-31 - Neptune retains its German operations, Vår takes over the Norwegian portfolio and Eni scoops up the rest of the assets under the $4.9 billion deal.

NOG Closes Utica Shale, Delaware Basin Acquisitions

2024-02-05 - Northern Oil and Gas’ Utica deal marks the entry of the non-op E&P in the shale play while it’s Delaware Basin acquisition extends its footprint in the Permian.

California Resources Corp., Aera Energy to Combine in $2.1B Merger

2024-02-07 - The announced combination between California Resources and Aera Energy comes one year after Exxon and Shell closed the sale of Aera to a German asset manager for $4 billion.

DXP Enterprises Buys Water Service Company Kappe Associates

2024-02-06 - DXP Enterprise’s purchase of Kappe, a water and wastewater company, adds scale to DXP’s national water management profile.

Pioneer Natural Resources Shareholders Approve $60B Exxon Merger

2024-02-07 - Pioneer Natural Resources shareholders voted at a special meeting to approve a merger with Exxon Mobil, although the deal remains under federal scrutiny.