Stupp's 24-inch, high-frequency welding mill was the first in North America. The firm produces, coats and transports line pipe joints up to 80 feet in length, reducing the number of expensive girth welds that need to be made in the field. Source: Stupp Corp.

Learn more about Hart Energy Conferences

Get our latest conference schedules, updates and insights straight to your inbox.

John Stupp manages a concreteweight coating plant on the Mississippi River a few miles from its Baton Rouge, La., campus to provide operators pipe for use in wet or marshy areas. The concrete provides mechanical protection against anchors and pulls while decreasing pipe buoyancy. All photos courtesy Stupp Corp.

North America’s midstream has enjoyed a significant growth spurt in the past decade with the unconventional shale boom—and that means thousands of miles of new pipe added to the nation’s already outstanding transportation infrastructure. Much of that pipe has been supplied from Stupp Corp., which credits its role as “producing the pipelines that form the backbone of our continent’s energy infrastructure.” Its CEO took time to visit with Midstream Business to reflect on his firm’s distinguished past—and vision for the future.

MIDSTREAM Your parent firm has more than a century of experience supporting infrastructure development. How have you seen the business change in recent years?

STUPP The current company was started in 1856 by my great-great-grandfather. He came over from Germany and really was, for lack of a better description, an artistic blacksmith. He could work iron into anything. He started making farm implements and then he got into things like jail cells and all sorts of other stuff. Then he brought his three sons into the business in the 1870s and 1880s. They got the company involved in bridge fabrication in the mid-1880s when the first federal highway program was started. Being located in St. Louis, we were kind of on the western edge, the industrial part of the country. So we actually supplied a lot of bridges for places west of St. Louis.

The company segued into paper mill, sugar mill and steel mill structures in the early 1900s. We got involved in the pipe business in 1952, first to supply some pipe for the Korean War effort. Then we moved our location to Baton Rouge, La., to be involved in the energy business.

To cover interesting parts of my career, I started in 1974. I spent two years in the Army and then I went in the business. I was pretty much focused on the fabrication side of things up in St. Louis but always had an interest in the pipe side of the business. As I look back, the vast majority of the pipe work that we did in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s was all natural gas. There were occasional oil or products lines going in here or there, but almost everything we did was focused on natural gas because the oil infrastructure was pretty much there, even though it was aging. There wasn’t that much demand for new oil pipelines.

When the shale boom began, it completely changed the dynamics of what we were doing, and it created, obviously, a market for crude oil lines and product lines, like ethane as well as for natural gas. So as the pricing for the resources changed, it really drove our activity. One customer had ordered some pipe to go to the Haynesville Shale, and before we started shipping it, they called and said, “No, no, don’t ship it to the Haynesville. Ship it to the Eagle Ford”—which I hadn’t heard of up to that point. So it was exciting to see how much effort went into chasing the high-dollar returns for the producers.

In 2009, we added a spiral mill to make larger diameter pipe. Our HFW [high-frequency welding] mill produces up to 24-inch pipe with a straight seam, and then we started making 30-inch to 60-inch pipe in our spiral facility. That part of the business has been hit worse because the larger-diameter projects are more cyclical than the smaller-diameter ones.

It was all rewarding in terms of the fact that there were so many more opportunities for pipelines. When the bubble burst—and I don’t think any of us were as intelligent as we should have been about when the bubble was going to burst—all of a sudden we went from both mills working 20 hours a day, six days a week to a pretty grim 2016.

MIDSTREAM What do you find to be the most rewarding thing about what you do in your job?

STUPP That’s a good question. I’m the CEO of our holding company, so I oversee all parts of our business, but if I’m focused just on the energy side I really get excited when we win a good project. What we’re really trying to do is to help our customers make their projects successful.

The shale buildout created a lot of new MLP customers who didn’t necessarily have the bench strength that some of the big companies do. I think we were able to add more value to some of the smaller companies because of the experience we’ve had over the years. I think we’re gaining opportunity. We can help somebody that maybe doesn’t have the amount of talent that a Kinder Morgan or an Enterprise Products or an Energy Transfer has.

MIDSTREAM What was the most challenging project you’ve been involved in during your career?

STUPP One that was really interesting to me was a 562-mile project in Colombia for Enron some years ago. We had really not exported a lot of material at that time. So we had to learn all the ins and outs of the international shipping terms, and the way to get our product to a foreign country, and get the rhythm of trans-ocean shipments—plus we had to spend some time in Colombia to get an understanding of what was going on down there. As I think about it, that was probably the most interesting project. It was very rewarding, and we learned a few expensive lessons along the way.

MIDSTREAM Where do you see the greatest pipeline activity in North America?

STUPP I’d say probably the Permian Basin right now is the hottest area.

MIDSTREAM There has been a lull in projects with the commodity price downturn. Do you see a turn-around coming?

STUPP I think there are two factors. One is what can happen in Washington? And two, what will global pricing be for crude oil? If the new administration takes some real interest in what happens with the resources in this country and there’s a positive economic vibe, then I could see some more activity. There is a turnaround coming. I just can’t predict when.

MIDSTREAM What advice would you give a midstream operator planning a major project?

STUPP I would encourage them to engage pipe manufacturers as early in the planning process as possible. Those of us who are in the business really know a lot of the dynamics and have close relationships with the steel mills. At the moment, domestic steel prices have gone up after the steel companies received some trade protection against Chinese and South Korean flat-rolled steel imports.

Talking to different suppliers as early in the process as possible will help them determine what the reasonable goals for a project are and allow us to help them achieve their objectives.

MIDSTREAM How does your overseas business differ from the North American market?

STUPP At the moment, we don’t have any overseas business. That’s really driven by the strong dollar and the cost of domestic steel.

MIDSTREAM Is that something that may change then, if the dollar weakens at some point in the future?

STUPP Yes, probably the bigger part of it is that the world economy is not growing. The U.S. is already the lead market, so it’s a magnet for more activity to take place here than in other places.

We did a fair amount of export work in the 1990s, which was really driven by, first, the deregulation in the natural gas business. Then secondly, what I call the re-regulation, where the transmission companies had the opportunity to build a lot of competing lines that they weren’t allowed to build when the business was more regulated. But their returns were regulated. So they really were making money on the transportation.

I think a lot of the companies said, “This is not all that great,” so they looked for opportunities in Central and South America and Asia, where they could make a better return. We benefitted from that and sold a fair amount of pipe into Mexico and Central and South America. But it all dried up when the Asian financial crisis hit in 1999. It rippled through South America and then spread to Europe.

The U.S. operators who were building projects in other places said, “You know, we’re not really doing any better down here in Colombia than we were in Texas, and we have a lot of other risks.” Since the big bulk of our international business was really with the U.S. customers, or U.S. connections in these other countries, when they abandoned those efforts our opportunities in those countries left with them.

MIDSTREAM What about Mexico with the changes in its energy laws? It seems to have spurred a significant amount of midstream work.

STUPP Yes, interestingly, there is a lot of work going on in Mexico and a lot of it is for the Mexican electrical utility, CFE. It’s changing over to natural gas that they’re importing from the U.S. to generate electricity. However, the Mexican trade authority has put up trade barriers for U.S. pipe. You might say they built Mr. Trump’s wall—except on their side of the border. The Mexican equivalent of the U.S. International Trade Commission has issued significant duties on both longitudinal and spiral-seam material, to the extent that companies in the U.S. cannot participate in the Mexican market.

We’re in the process of trying to get the U.S. trade representative to file a case that the Mexican rulings are violating international trade laws because, basically, there are a couple of Mexican producers that already benefit from local content requirements which give them at least 50% of any internal oil and gas project. They get half the pipe already and now they’re trying to get the other half by blocking imports from their market. It’s a very disturbing situation.

Our NAFTA partner put up these barriers. U.S. pipe producers have a triple whammy working against us.

When there are large projects with long lead times, we’re faced with pipe imports coming in from South Korea that are made of Chinese steel, or even Korean steel that’s priced to meet the Chinese prices. They come into this country below our cost of domestic steel. There are duties on the Chinese steel imports, but there are very minimal duties on pipe imports from South Korea.

One of my friendly competitors has described it as the Koreans are laundering Chinese steel and shipping it into this country. So we’re reaching out to the new administration to say, “If you want to have a vibrant steel industry in this country, the steel industry itself needs trade protection. But the midstream products also need protection because you’re not really helping your steel companies if the domestic pipe producers are being undercut by Korean pipe imports.”

It’s a really tough situation. You’ve got Mexico. You’ve got trade protection against laundered Chinese material. Then you’ve got the environmental, the permitting issues. Let’s put it this way: The permitting issues are keeping pipelines from being built in certain places, but I think there’s a good chance that that’s going to change in this new administration.

MIDSTREAM Customization vs. standardization: What trend do you see?

STUPP Stupp has really been a leader in  this area for a long time. It kind of goes to one of your earlier questions: We are trying to figure out what our customers need to do to be successful. We were the first manufacturer to produce 60-foot joint lengths and then 80-foot joint lengths, recognizing the expense in the field to do girth welding. So the longer the pipe, the less field welds that the end user needs. It reduces their construction costs.

this area for a long time. It kind of goes to one of your earlier questions: We are trying to figure out what our customers need to do to be successful. We were the first manufacturer to produce 60-foot joint lengths and then 80-foot joint lengths, recognizing the expense in the field to do girth welding. So the longer the pipe, the less field welds that the end user needs. It reduces their construction costs.

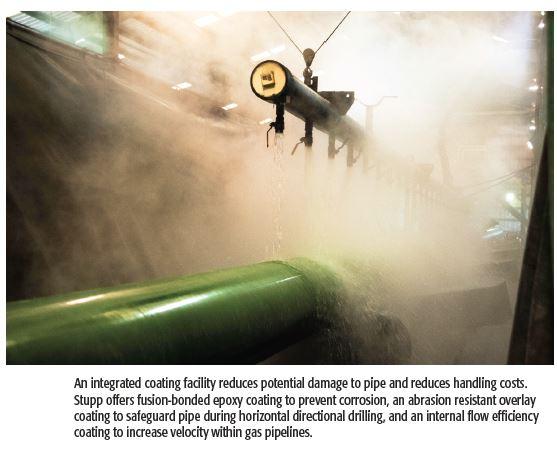

We’ve tried to stay ahead of the trends. We were the first company to install a 24- inch HFW mill. Then we started our own coating operation back in 1994. So we really controlled the combination of the pipe, coating and transportation to the end user and helped them reduce handling and logistics costs on their projects. We’re trying to discover, “How can we be more competitive, and how do we help the customer be more successful?”

Way back when, there was a standardization of wall thickness in steel, and we led the charge to say, “What’s the operating pressure at which you want your line to operate? Maybe we can sell you thinner wall, higher grade material, or just right-size the wall thickness and the diameter for what you’re trying to move.”

I think customization—even though I don’t think we always get paid enough for it—is really where the customers

want to go. It’s interesting that customers develop, in a lot cases, rigorous specifications that exceed API requirements because they believe it gives them some advantages. So everything we do is really a unique project. There’s no standard anymore, I think.

MIDSTREAM Pipeline integrity is of growing importance due the public’s interest in safety and environmental protection. What is Stupp doing to respond to this emphasis?

MIDSTREAM Pipeline integrity is of growing importance due the public’s interest in safety and environmental protection. What is Stupp doing to respond to this emphasis?

STUPP I think the whole industry has been focused on this in terms of the nondestructive testing that really builds quality into the production of our pipe. We have, obviously, nondestructive, and some destructive testing, that takes place on really every piece of steel that we buy to make into pipe.

Furthermore, there’s been a much bigger emphasis on traceability. The customer needs to know what was the profile of this steel? What was the process that was used to make the steel into pipe—and the same with the coating? What tests were performed? At each step we’re really trying to make sure that we, and therefore the customer, know the pedigree of each piece of pipe.

We invested in an electronic traceability system that we offer to the customer if they want it, to give them more real-time visibility on the life of the pipe from the steel mill to the ditch. That’s called the SPOT [Setting Precedents On Traceability], Traceability Solution. We’ve partnered with Jones Cos. on this.

MIDSTREAM Where does the midstream go from here?

STUPP I want to see America take advantage of all the resources we have under the ground, and obviously there are economics that drive that. I really want to see that the operators recognize the value that the pipe producers, the coating companies and the construction companies can add. Hopefully the guys like us, who have made significant capital investments over the years to be able to make the product, will be seen as partners by the midstream and transmission companies. I think our experience adds comfort that the product we provide is going to take care of the environment and protect the people who live around pipelines.

I think the challenge is to see all this potential for growth, which you would think should carry on because the U.S. is sitting on all of these resources, but obviously we’re in a global pricing situation, and if the guys in Saudi Arabia would rather produce at lower prices to prevent the shale drillers from making a decent return, then the activity dries up, as we saw over the past two years.

Long term, I think the pioneers who developed fracking and horizontal drilling have done our country a great service. Energy independence is within our grasp, as long as the market conditions improve. Plus, I think the producers will be able to reduce their costs significantly once they get back into fuller production.

Paul Hart can be reached at pdhart@hartenergy.com or 713-260-6427.

Recommended Reading

E&P Highlights: Feb. 12, 2024

2024-02-12 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including more hydrocarbons found offshore Namibia near the Venus discovery and a host of new contract awards.

ChampionX to Acquire RMSpumptools, Expanding International Reach

2024-03-25 - ChampionX said it expects the deal to extend its reach in international markets including the Middle East, Latin America and other global offshore developments.

Permian Activity in ‘Low-to-no-growth’ Mode for First Half

2024-02-22 - After multiple M&A moves in 2023 and continued E&P adherence to capital discipline, Permian Basin service company ProPetro sees the play holding steady.

Analysts, SLB Execs See Stability in $7.7B ChampionX Deal

2024-04-04 - The acquisition of ChampionX vaults SLB’s chemical production business to No. 1 globally and orients SLB's business toward resource recovery that is less tied to price volatility.

OEP Completes Acquisition of TechnipFMC’s Measurement Solutions Business

2024-03-27 - One Equity Partners said TechnipFMC’s measurement solutions business will be rebranded as Guidant and specialize in measurement technology, automation solutions and global systems.