The low-emissions profile of hydrogen has propelled the energy carrier into the global spotlight, but what will it take to scale and expand beyond its existing pool of buyers?

Is a global carbon tax the answer?

Air Products CEO Seifi Ghasemi believes it is simple, reasonable and political poison.

“People like me have always been promoting the fact that the best solution to this thing worldwide is a carbon tax. It is very simple. It will create a demand,” Ghasemi said April 24 during the BNEF Summit in New York. “But politically, nobody wants to create the so-called carbon tax and call it carbon tax… In the real world, it’s not happening because if you promote a carbon tax, you lose Pennsylvania, Virginia and I guess you never become president of the United States. So, nobody wants to talk about carbon tax.”

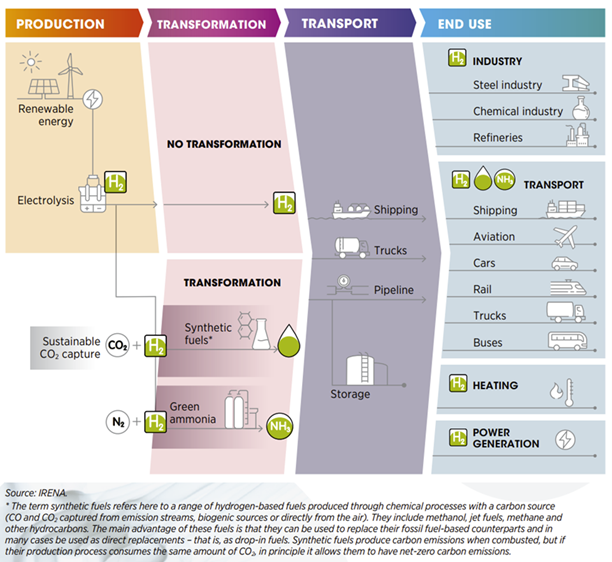

Talk turned to hydrogen during a panel on the energy transition, trade and supply chains. Hydrogen is used mostly today in oil refining; production of ammonia, methanol and steel; and to generate heat or power. However, it also has the ability to power fuel cells, generate electricity and serve as a transportation fuel, displacing carbon-emitting fossil fuels.

‘Speed dating’

Testing supply and demand is part of the thinking behind hydrogen hubs.

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) will dole out $7 billion this fall for the development of six to 10 regional clean hydrogen hubs across the U.S.

“The idea there is to try to create little markets and ecosystems where you can test both the infrastructure, the technology, the supply, the demand,” said Sarah Ladislaw, special assistant to the president and senior director of Climate & Energy for the U.S. National Security Council. It’s “like trying to create this world around which you can build all the commensurate parts that are required for a hydrogen economy in the United States.”

While it may not do everything perfectly, hydrogen markets still need to be established. That will require getting community support, needed infrastructure and offtake agreements for various markets, she said.

“We have more hydrogen literacy now than we did five years ago as a result of these kinds of policies and programs,” Ladislaw said. “Does it make sure that those markets are going to develop smoothly everywhere? No, absolutely not. But it does put the sort of speed dating aspect into an industry.”

‘Overhyping hydrogen’

Global production of hydrogen is about 75 million tons per year (mtpy) with an additional 45 MtH2/year as part of a mix of gases, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). That is equivalent to 3% of the global energy demand, IRENA said, roughly about the amount of energy consumed in Germany annually.

“We need to be careful about overhyping hydrogen,” said Nancy Pfund, founder and managing partner of DBL Partners. During the nearly 20 years the venture capitalist firm has been investing, Pfund said the firm could have invested in a stack of hydrogen deals taller than the ceiling but it chose to back companies like Tesla and solar instead. “I wouldn’t be sitting here today had we made a choice to invest in those hydrogen deals.”

Using vehicle sales as an example, she pointed out that about 11 million EVs were sold last year compared to less than 100,000 — total — for fuel cell cars. Pfund, however, acknowledged hydrogen’s potential.

“We need to invest in clean hydrogen. There will be great applications. But in some ways, it’s like that old Carly Simon song [the one she might’ve written]: ‘You’re so vain you probably think the market share is about you.’”

EVs, batteries, solar and wind are dominating renewables, she noted — later pointing out the latter three have lessons to share about driving down costs.

The ‘only driver’

Costs are seen by many as a barrier to hydrogen growth, particularly for hydrogen produced from renewable electricity using expensive electrolyzers.

Efforts are underway to improve overall economics, with policies such as the Inflation Reduction Act providing production tax credits and the DOE’s Hydrogen Shot aiming to cut clean hydrogen costs by 80% to $1 per kilogram within one decade, opening new hydrogen markets.

Ghasemi takes issue with comparisons of hydrogen costs to fossil fuel costs.

“If the aim is to make green hydrogen or blue hydrogen cheaper than hydrocarbons, that will never happen. That is … not the goal,” Ghasemi said. “The goal is to clean the climate, and whatever it cost it costs.”

Previous energy transitions such as from wood to coal to oil were economics based, he said; however, “clean energy will be more expensive than hydrocarbons the way we are using it today. Therefore, the only driver that will make clean energy happen is policy.”

Recommended Reading

US Drillers Add Oil, Gas Rigs for First Time in Five Weeks

2024-04-19 - The oil and gas rig count, an early indicator of future output, rose by two to 619 in the week to April 19.

Strike Energy Updates 3D Seismic Acquisition in Perth Basin

2024-04-19 - Strike Energy completed its 3D seismic acquisition of Ocean Hill on schedule and under budget, the company said.

Santos’ Pikka Phase 1 in Alaska to Deliver First Oil by 2026

2024-04-18 - Australia's Santos expects first oil to flow from the 80,000 bbl/d Pikka Phase 1 project in Alaska by 2026, diversifying Santos' portfolio and reducing geographic concentration risk.

Iraq to Seek Bids for Oil, Gas Contracts April 27

2024-04-18 - Iraq will auction 30 new oil and gas projects in two licensing rounds distributed across the country.

Vår Energi Hits Oil with Ringhorne North

2024-04-17 - Vår Energi’s North Sea discovery de-risks drilling prospects in the area and could be tied back to Balder area infrastructure.