[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the November 2020 issue of Oil and Gas Investor magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

In the northern Delaware Basin in the past couple of months, operators with leases on federal land were rushing to secure their drilling permits. U.S. presidential candidate Joe Biden has said he will forbid new drilling on federal land.

And those leases weren’t cheap. Matador Resources Co. paid up to $95,000 an acre in 2018 in a Bureau of Land Management (BLM) sale.

Bernstein Research senior analyst Bob Brackett reported in early October that, in the 28 months prior to February 2020, the ratio of federal-to-state permits issued in Eddy and Lea counties, N.M., was nearly always less than 60% federal.

That jumped to 70% in February and 80% in March and has been at least 70% each month since, according to Enverus data.

cash flow, said Bernadette Johnson, vice president, market intelligence, with Enverus. “You

can’t drill twice as many wells for

100% more cost and only get 60%

more production. It simply doesn’t

work.”

“E&Ps are stockpiling federal permits to be on the safe side,” Brackett wrote.

Matador holds 127,600 net lease and mineral acres in the Eddy and Lea counties and in Loving County, Texas; about 28% of it is on federal land. About 62% of that is HBP, the company reported in an update in July.

Once its Stateline property is HBP before year-end by putting online at least one more well (at the Voni unit), 70% of its federal acreage will be HBP, it added. The rest of its federal leasehold doesn’t expire before 2028.

Meanwhile, it had 218 permits, and 68 more were underway that it anticipated receiving before year-end.

In Matador’s second-quarter earnings call, Mike Scialla, a managing director at Stifel Financial Corp., asked what percentage of Matador’s leasehold could go undrilled if Biden wins and forbids new permits.

Joe Foran, Matador chairman and CEO, said that “The chances of them saying you can’t drill on your leasehold are fairly slim” since the federal government would probably have to use imminent domain and, if winning that, then “they’ve got to pay for it.”

If a permit has already been issued, “I think they’re going to allow you to drill it,” Foran said. “The federal government is going to need the money.”

Matador and other operators with federal permits have two years to drill the wells that have already been permitted. BLM leases are for up to 10 years.

If needed, though, Matador has “a lot of A-plus wells that are not on federal leases,” Foran said. If it couldn’t drill the federal land, “there’s still plenty of opportunities out there” on state and private land.

At the state level, New Mexico’s governor has been supportive of the industry, he added. Should there be any changes on any front, “I think we’re nimble enough to change with them.”

Spacing, Contango, Pecos County

Meanwhile, Matador and other Delaware operators have done most of the science-ing needed on well-spacing during the past few years. Early tests of tighter and tighter spacing hadn’t gone well.

Bernadette Johnson, Enverus vice president, market intelligence, told attendees in Hart Energy’s virtual DUG Permian conference in September that there is a midrange.

In one case study, Johnson focused on Contango Oil & Gas Co.’s Wolfcamp A program on the southern edge of the Delaware in Pecos County. Other formations are being targeted by operators in the area, but Wolfcamp A is the most common, thus examining that one, she said.

“In the entire Delaware Basin, you can see a bit of upspace behavior,” she said.

Operator spacing in Contango’s area is different than the basin average and further differs within the study area. “There is a pretty big disconnect between how the wells were spaced from 2018 to 2019,” Johnson said.

“So, even in the area with very similar rock, you do see different behavior from different operators and different results reflect that.”

Noble Energy Inc. (now owned by Chevron Corp.) and Occidental Petroleum Corp. have upspaced significantly, “which seems to have a positive impact on their well productivity.”

There is also staggered development. Noble, for example, is wine-racking.

“This doesn’t work everywhere, but [here] it allows you to target at different depths and where you can squeeze a few more wells in without degradation of the type curves and, of course, the corresponding free cash flow,” Johnson said.

Normalizing laterals to 10,000 ft, 2,500 pounds of proppant and 60 bbl of fluid per foot, “Your very tightly spaced wells have your lowest EURs,” she added.

The highest EUR is derived from spacing between 1,110 ft and 1,220 ft (an EUR of about 800,000 bbl). Meanwhile, too wide makes for poorer results (725,000 bbl or about the same as wells spaced between 930 ft and 1,050 ft).

“It’s not always that you spread out your wells enough and you will continue to see EUR improvement,” she said. “There really is an optimal way to drill these wells based entirely on what the rock looks like, how you complete them and the type of communication you see between them.”

Of course, more resource can be recovered from tighter and tighter spacing, she acknowledged. But, for a 1,220-ft-spaced well and for a 660-ft-spaced well, EUR declines from 804,000 bbl to 632,000 bbl.

“You have twice as many wells here with the 660 [ft-spaced well], but you get about 60% of production.”

Before 2018, “You would have drilled [the tighter-spaced] wells all day. You would have been going out with the intention of primarily growing your production volume,” she said.

But the focus is now on free cash flow: “You can’t drill twice as many wells for 100% more cost and only get 60% more production. It simply doesn’t work.”

Spacing, Noble, Reeves County

Moving north, Johnson looked at Reeves County. “Noble has had the most drastic changes to spacing design in this time period,” she said.

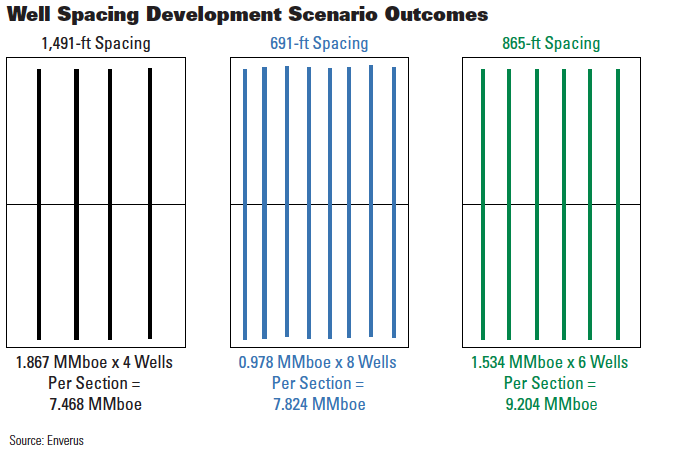

It went from about 1,491 ft to 691 ft then up to 865 ft. The 691-ft wells led to a higher IP, but “EUR is significantly better with the 865-ft program,” Johnson said.

The poorest EUR was from the 1,491-ft wells. But those are older—“They weren’t completed the same way”—and the data isn’t normalized.

When normalizing the 1,491-ft wells and others to 10,000-ft laterals, 2,500 pounds of proppant and 50 bbl/ft of fluid, EUR is 1.9 MMbbl (three times more than the smaller drilled and completed) from the 1,491-ft versus 1.5 MMbbl from the 865-ft well and 980,000 bbl from the 691-ft well.

In the 865-ft development scenario, the IRR is 65% at $55 oil, $2.30 natgas and $20 NGL. Six of these can fit in one section (versus four 1,491s and eight 691s).

For Noble in Reeves County, “Choosing to space wells at six per section instead of eight potentially added about $250 million of free cash flow,” Johnson said. It’s an example of “rolling up all the different pieces.”

It isn’t enough to “maximize production volumes anymore. It’s all about free cash flow. And in this specific area, it’s the 865- foot spacing program that really generates the best return for Noble.”

Spacing, WPX, northern Delaware

WPX Energy Inc., which is merging with Devon Energy Corp., bought Felix Energy II LLC in March, taking up its 58,500 net acres that were primarily in Loving, Winkler and Ward counties, Texas.

As private-equity-backed Felix’s strategy was to sell, “You’re testing new zones and really stretching things out,” Clay Gaspar, WPX president and COO, told conference attendees. The testing “was even beyond what we did in Stateline.”

It included some “interestingly” spaced and staggered wells in megapads that “we did not like.” But Felix had already backed off of this by the time WPX was talking to them, Gaspar added.

“They had moved away from that and were drilling wells much farther spaced.”

The megapads are appearing in public data now and, as the new owner, they’re showing up as WPX-operated wells. “And it’s just not very impressive,” Gaspar said.

“What I would ask everyone to look at is the better-spaced wells. [They] are phenomenal.”

WPX was completing the Cathedral wells on University Lands on the former Felix property in early September. “And we can tell the ones that we steer versus the ones that Felix steered,” he said.

“We know we’re going to get better well results and better cost structure as well—a compounding effect that juices the returns that we had underpinning the acquisition model.”

In spacing, there are two considerations: How close the wells are and “how big of a bite do you take?”

In one unit, say there are ultimately dozens of wells. There is the temptation, of course, to place as many as possible—say, 12 at a time rather than six—paring the cost of having to go back to the unit twice as many times to fully develop the unit.

But it will take twice as long to get all 12 wells online than six, Gaspar noted. “So, we have to think about, as we scale, what’s the appropriate bite size? Those two components are both very important.

“I think we understand spacing a lot better than we ever have. I think in the Williston—very, very, very mature basin—we’ve conquered that. We’ve understood that for years.

“In the Delaware, to be honest, we’re still figuring it out.” And the approach changes at $40 oil from $65 oil, he added.

WPX has upspaced its Delaware wells, including on the Felix property, and “that’s proving to be very substantially better-quality wells.”

Wells landed and completed at one time are somewhere between six and 10. “As we continue to scale up as an organization over the years, we can afford to take bigger bites.”

(Editor’s note: Gaspar’s remarks were made prior to the WPX-Devon merger announcement.)

Spacing, UpCurve, Reeves County

Using the Enverus spacing tool that Johnson used in the Delaware case studies, Dena Demboski, vice president, operations, UpCurve Energy LLC, said spacing can come to what is the E&P’s business model.

“Selecting optimal well locations would be much easier if we all knew our exit date. It becomes much harder when you start looking at full-field development.”

UpCurve has about 10,000 contiguous acres producing 7,000 bbl/d (about 11,000 boe/d) from 17 horizontals in central Reeves County, Texas, including 150 proved undeveloped wells (PUDs) in the Wolfcamp A-Upper, Wolf B and Wolf C.

The E&P was founded in 2015 by ConocoPhillips colleagues, including Demboski, backed with $120 million from Post Oak Energy Capital LP. The Reeves position began with 2,000 acres purchased from Elevation Resources LLC.

Like what Enverus’ Johnson found in the Noble case study, the average spacing in Reeves County is six wells per bench per section or 880-ft spacing.

vice president, operations, with UpCurve Energy LLC.

Demboski said, “We’re seeing a 13% degradation in the EUR for child wells across Reeves County.” The first 10% comes from spacing among parent wells; the additional 3%, from the child well.

UpCurve’s own results are in line with the data, she added. “We’re also looking at doing some preloads prior to coming in and fracking our infilled wells to help protect the parent,” she said.

And diverters may help. “So, rather than reduce sand volumes, we’re looking at maybe tweaking the diverter design—whether it’s the multiple diverters mixed together and then deploying them a few different times during the actual stage.

“So, I’m hoping to see some good success with that as we have DUCs coming up.”

Managing choke, UpCurve

Most of UpCurve’s wells are 2 miles. It had two DUCs in early September that it planned to complete by year-end, and it plans to resume drilling with one rig in the first quarter of 2021.

It’s flaring less than 1% of its gas, while the basin average is about 3%. It expects to be free-cash-flow positive in 2021.

Adjacent neighbors include Colgate Energy LLC (25,000 boe/d; 30,000 net acres); Camino Natural Resources LLC (15,000 boe/d; 35,000 net acres); Tall City Exploration III LLC (8,000 boe/d; 23,000 net acres); and Primexx Energy Partners Ltd. (30,000 boe/d; 40,000 net acres).

Demboski cited a Simmons Energy report that ranked private Delaware operators. “Across the Delaware, you can see a trend where the six-month oil cume per 1,000 feet has declined for the last couple of years, which is likely a factor of infill drilling.”

UpCurve is pumping some 3,200 pounds/ft of sand with 87 bbl/ft of fluids, making it “one of the more aggressive” privately held operators in the Delaware in completion design, she said.

The basin average is 2,300 pounds/ft and 49 bbl/ft among the privately held Delaware operators that Mark Lear, Simmons senior research analyst, examined.

UpCurve’s six-month production outperformed the 2019 Delaware average by 15% with 17,400 bbl per 1,000 lateral ft versus an average of 15,100 ft. The UpCurve production is 80% liquids.

“We have proven with these results that our area, which was originally thought to be noncore, competes with anything else in the basin,” Demboski said.

An advantage is the presence and thickness of a carbonate barrier between Upper and Lower Wolfcamp A in the UpCurve leasehold, she said. “This carbonate feature is not present across the entire basin as a whole. And it fluctuates in thickness.”

It has also managed wells for cume versus IP. “Our strategy hasn’t been to chase IP right off the bat,” she said. “We strive to reach a strong IP of around 1,200 bbl/d early on and manage our choke to plateau production closer to the peak production with minimal decline for about three months.”

M&A 1: ‘Make what you have work’

Permian E&Ps’ valuation by prospective buyers and investors is explained only half by individual wells’ returns, Bernstein’s Bracket wrote in early October.

“The market focuses on P/CF [price-tocash- flow ratio] more than EV/EBITDA. We believe this is a function of trust in cash flow more than EBITDA and a belief in the ability to look past net debt.”

The market’s valuation of Permian pureplay operators is more obvious, he added. It’s divided into “a cheap ‘overly levered’ camp and a rightfully more expensive better-balance- sheet camp.”

On March 5, before WTI crashed, Brackett wrote, “Permian consolidation would be a tough way to play E&Ps.” Since then, Chevron Corp. has acquired Noble, WPX is merging with Devon, Concho Resources Inc. is being acquired by ConocoPhillips and Parsley Energy Inc. is merging into Pioneer Natural Resources Co.—all of the sellers Delaware-focused.

“But near-zero premiums seem to be the starting point of the negotiation,” Brackett wrote. “Or perhaps it starts with ‘We’ll offer you a 30% premium to where your stock will be when we get around to calling back.’”

UpCurve’s Demboski said the E&P business model “that got us through the past seven years won’t get us through the next seven. Focus has transitioned from ‘growth at all costs’ to ‘make what you have work.’”

The traditional private-equity-backed model of “build and flip” to another—usually publicly held—E&P “is no longer a viable strategy,” she said.

Instead, private E&Ps are transitioning to full-field development of PUDs rather than only building an inventory of them. The goal: free cash flow, a self-funding model, lowering LOE and completing the infrastructure.

“Skillsets at the privates are evolving,” she said. “They aren’t just land business development shops anymore. There’s more emphasis that’s been made to develop the in-house technical operating and land expertise within.”

In addition, “There are several opportunities here to consolidate quality positions in the basin,” Demboski said. UpCurve, in particular, “is in the top quartile of production for the Delaware Basin.

“We have proven highly economic inventory and multiple benches. We are free-cashflow- positive in 2021 and looking for growth opportunities across the Permian Basin.”

M&A 2: ‘Permanent disadvantage’

Parsley’s roughly 250,000 net acres are in the southern Delaware (111,000 acres) and across the Midland (137,000 acres). In January, it picked up Jagged Peak Energy Inc., which was flaring “a materially higher percentage of their gas” versus Parsley’s sub-3%, David Dell’Osso, Parsley executive vice president and COO, said in the conference.

“A big part of that acquisition was leveraging our combined scale in solving this problem.” Bringing in Jagged, Parsley’s flaring jumped to 20%. It’s gotten it down to sub-2% now.

“And we’re not done,” Dell’Osso added. “We aim to eliminate routine flaring across our asset base as we go forward.”

He expects some smaller Permian operators may be, “probably frankly, at something of a permanent disadvantage” in achieving scale.

“So, I feel like there’s going to be a subset of companies that are simply going to be forced to consolidate in some manner [and] not going to be the consolidator.”

(Editor’s note: Dell’Osso’s remarks were made prior to the Pioneer-Parsley merger announcement.)

Parsley is in the upper half in size among Delaware E&Ps on myriad metrics.

“I think we demonstrated with our Jagged Peak acquisition that we can very effectively be the consolidator,” Dell’Osso said.

“However, that was a very special transaction that was directly adjacent to our acreage footprint and that we knew well … There are only so many of those types of opportunities out there.”

Parsley has plenty of inventory, meanwhile, he added. But “I think consolidation has to occur.

“I just don’t know who is going to be the acquirer in some of these. But there’s no doubt in my mind the small folks are permanently disadvantaged.”

M&A 3: ‘No loss of our hunger’

WPX’s acquisition of Felix was after a roughly three-year hiatus from buying. WPX was looking all along, though, Gaspar said. “There was no loss of our hunger during that period.”

(Felix I, which focused on Oklahoma’s STACK and surrounding play, was bought by Devon in 2016. Felix II, now owned by WPX, will become part of Devon as well via the Devon- WPX merger.)

Arun Jayaram, E&P analyst for J.P. Morgan Securities LLC, wrote when the deal was announced that Felix’s wells tended to have lower IPs “but lower declines and higher oil cumes than WPX’s wells due to [a] ‘slowback’ choke-management strategy.”

Gaspar said in the conference the deal “plugged a hole between some incredible [WPX] Williston, high-oil-cut opportunities to some really incredible, economic [Delaware] Stateline opportunities that are about 50% oil cut,” Gaspar said.

Felix brought to WPX a 70% oil cut. “It filled that niche between 85% [Williston] and 50% [WPX Delaware].” And it gave WPX more running room, he said, adding another 1,500 gross 2-mile drillable locations.

“We know we are in the business of consumption. We consume our very best wells every day of the year. If we’re not replenishing, then we will run out at some point.”

It wasn’t a near-term concern, he added, “but having a little bit more scale to your opportunity set causes you to always high-grade and you end up with a better result.”

Ameredev, northeastern Delaware

Ameredev II LLC’s property sits among major E&Ps in the northeastern Delaware. Its acres are in a solid block approaching the Central Basin Platform, resulting in distinct, tight carbonate layers that limit vertical frac growth.

It “gives us some flexibility around which zones we co-develop or not in our initial development,” Parker Reese, Ameredev president and CEO, said in the conference.

There is also an abundance of proximal sediment, contributing to matrix porosity and high permeability. “It works really well where we are due to the kind of binary nature of lithology between hard carbonates and nice organic shale with high porosity.”

Ameredev’s first wells are showing strong performances from Wolfcamp X, Y, A and B. “We see EUR spaced off of that performance between 1.5- to nearly 2.5 million barrels equivalent for 2-mile laterals.”

Reese, president and CEO, but GOR drops quickly when moving north into the black-oil phase. “We have a very strong low-GOR black-oil reservoir all the way to the north of our position.”

Ameredev’s south-central Lea County property is the largest privately held contiguous position in the northern Delaware, he added. Formed in May of 2017, its 27,352 net acres (31,931 gross) were put together from 42 acquisitions, four trades and three divestments in its first 15 months.

Inventory is 400 locations. “It’s all set up for long-lateral drilling,” Reese said.

Production is about 6,500 boe/d, 70% oil. “It’s a WTI-spec barrel. On the eastern side of the Delaware, we are producing not condensate but real, black oil.”

Ameredev’s leasehold is updip. That drives low water saturation—less than 1.5 bbl per bbl of oil. In some wells, it produces almost no water.

“That means that we have more oil in place for a given volume,” Reese said. “We have more drive energy because that hydrocarbon is much more compressible than the water would be. And it means we have less water to dispose of.”

The southern end of Ameredev’s leasehold has a distinct gas-oil ratio (GOR), he added, “that we’ve subsequently spent a lot of time understanding and delineating.”

GOR drops quickly when moving north into the black-oil phase. “We have a very strong low-GOR black-oil reservoir all the way to the north of our position.”

Ameredev’s Holly unit was being drilled in March. Those five wells were DUCs in early September. Starting back up this fall, Ameredev planned to drill a sixth Holly. The DUCs and the sixth well should be online in the first quarter, Reese said.

Free cash flow is growing toward $100 million a year, he added.

Bone Spring

UpCurve’s Demboski said that, in addition to the prevailing Wolfcamp drilling in the southern Delaware, there has also been some Bone Spring development “that could potentially open up a new bench for us in the future.”

It’s something the team is keeping an eye on.

Up in the northeastern Delaware, Ameredev has taken core and logs in the Bone Spring, Reese said. On the eastern side of the Delaware, “The data we’re seeing is showing this to be a superior geologic setting.”

WPX is doing spacing in the Third Bone Spring before moving to development mode, Gaspar said, but it “competes with the greater Wolfcamp A that is our bread and butter.”

In the Wolf A, “We’ve got a recipe, we love it and we’re plowing through that. The Third Bone, I would say we’re pretty close.”

Second Bone Spring is also promising. Crossing the state line into New Mexico, Gaspar said, “It becomes the primary source. You go south of the state line, it just becomes quiet.”

WPX isn’t investing much in Second Bone right now, though, while it is “working through these very trying times in this very precious capital environment to invest in [Wolfcamp and Third Bone] and still put the oil in the tank every single day, every month, every quarter, so we don’t fall out of favor with the investment community, which is always a challenge.”

Meanwhile, Matador completed its first Third Bone Spring carbonate test, it reported this summer. In Loving County, its Larson 136H came on with 1,668 boe/d, 68% oil, or 224 boe/d per 1,000 ft of the 7,443-ft lateral.

“Matador believes this test result … indicates the prospectivity of the Third Bone Spring Carbonate, not only in [this] asset area, but also in other of the company’s asset areas throughout the Delaware Basin,” the company reported. It planned more tests.

The 3-mile lateral

WPX jumped to 2-mile laterals in the Delaware not so much as a technological leap, although “you take a pretty good leap of faith in doing so,” Gaspar said.

As 1-mile-plus laterals were clearly working in the basin, WPX jumped to 10,000 ft as soon as it had the contiguous land.

“We’ve since drilled 15,000-ft laterals—as a necessity; it’s not routine,” he said. “But we are understanding the effectiveness of those completions, of that flowback. Are you really getting that 3-mile incremental value?

“What do the economics and the value really say about that? There’s a lot in the industry going on there.”

Meanwhile, there’s spacing—tighter, both vertically and horizontally. “And we knew you’re probably going to step over the line,” he said.

“At some point, you go too far, and you have to kind of dial it back, and we’ve experienced that.”

But timidity isn’t a hallmark of the E&P industry; one doesn’t know what will be found if one doesn’t go there. “If you always leave your putt short, you’re never going to make the putt,” Gaspar said.

“So, we want to make sure and understand where that line is.”

Of course, he added, an operator wants to “be thoughtful about the scientific approach of taking that step and then being able to figure out ‘Okay, in today’s commodity environment, where is that line and how do we get to that optimal point of view?’

“That willingness to take that risk, that’s what our businesses is built on. The new exploration today is all about understanding that technology and innovation. That could be on the computer front or it could be on the drillbit- front—and anywhere in between.

“We have to innovate to maintain our position and even garner a few incremental spots along the way.”

Getting your data right

There’s the fundamental stuff to technology too. During the past couple of years, WPX went about the “incredibly unsexy work” of something as simple as getting its data right, Gaspar said.

It’s making sure the well’s name is consistently the same in the mother database, for example. Is it the Smith 1 or the Smith #1? Is the working interest 66.7% or 66.67%?

Inconsistencies “can make the simple work and the really tough work equally more difficult than it should be,” he said.

Productivity and achieving the best results are lost if “our most brilliant employees spend about 80% of their time gathering and curating and upping the quality of the data, massaging it to the point that they can do their 20% of real value-accretive work.”

The internal goal is, “If we can simply double that 20% to 40%—and 60/40 is nothing to brag about—you double the productivity of your best and brightest around the organization.”

After getting the mother database into shape, the team that did it would, rightly, “try and brag about it. ‘Hey, we did 75,000 records and we cleaned all this up.’”

They received “a collective yawn because ‘Ah, data.’”

But Gaspar gets it. “It’s the foundation that everything else is built on.” About 1.5 years later, “some of the tools and apps and really cool things that took us weeks and weeks to do before [now take] a press of a button.”

Maybe that’s a bit of over-simplification, he said, but, by reducing the time to get the data,

“We’re able to do more and more iterations to get to the better answer.

“And ultimately that creates very significant value.”

Recommended Reading

Hess Midstream Announces 10 Million Share Secondary Offering

2024-02-07 - Global Infrastructure Partners, a Hess Midstream affiliate, will act as the selling shareholder and Hess Midstream will not receive proceeds from the public offering of shares.

Venture Global Acquires Nine LNG-powered Vessels

2024-03-18 - Venture Global plans to deliver the vessels, which are currently under construction in South Korea, starting later this year.

Imperial Oil Shuts Down Fuel Pipeline in Central Canada

2024-03-18 - Supplies on the Winnipeg regional line will be rerouted for three months.

Hess Midstream Subsidiary to Buy Back $100MM of Class B Units

2024-03-13 - Hess Midstream subsidiary Hess Midstream Operations will repurchase approximately 2 million Class B units equal to 1.2% of the company.

Apollo Buys Out New Fortress Energy’s 20% Stake in LNG Firm Energos

2024-02-15 - New Fortress Energy will sell its 20% stake in Energos Infrastructure, created by the company and Apollo, but maintain charters with LNG vessels.