[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the December 2020 edition of Midstream Business. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

Every once in a while, what’s old becomes new again. It only takes someone to champion it and nurse it back to good health, even when the odds seem stacked against it.

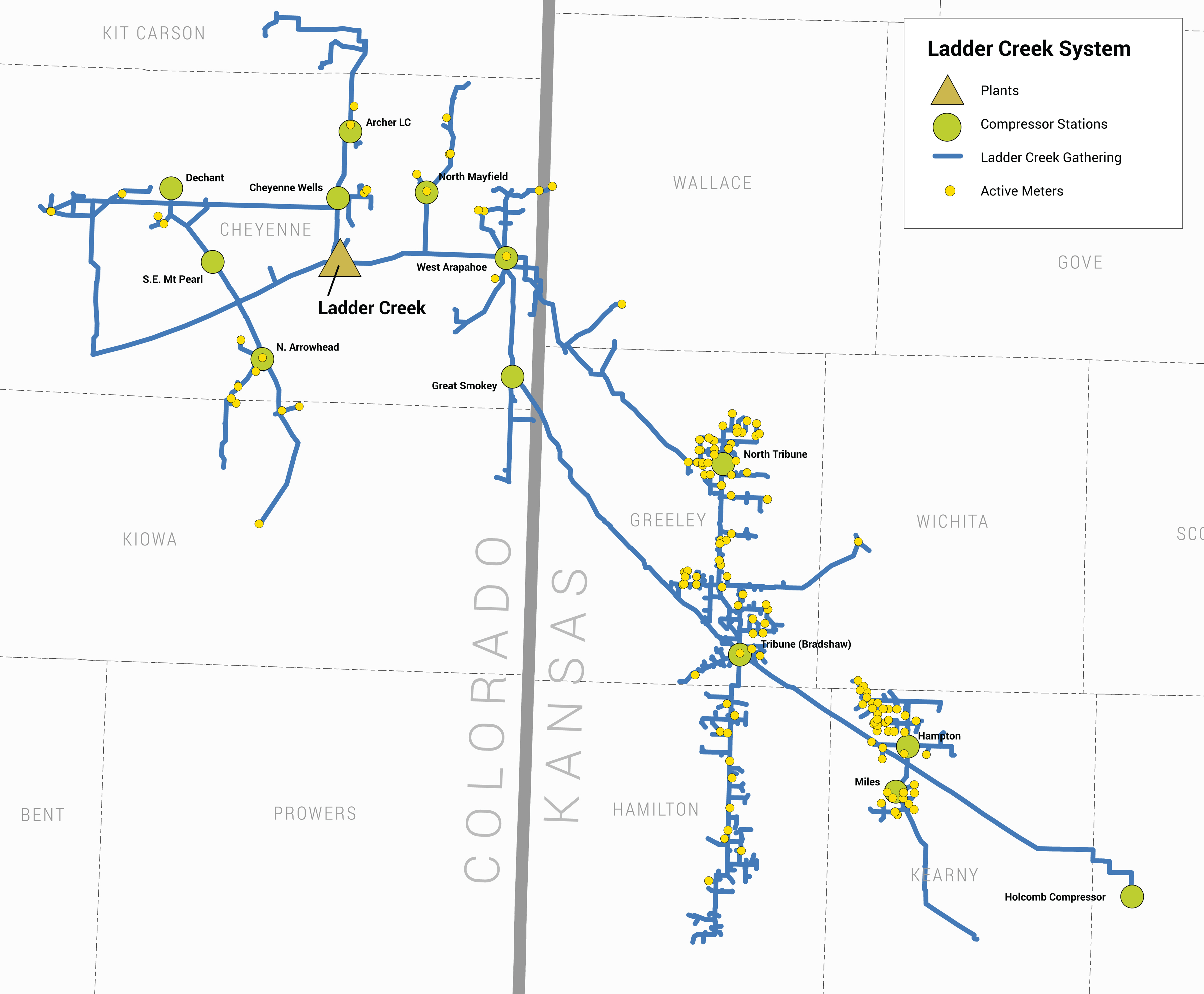

Durell Johnson, CEO of Tumbleweed Midstream, saw the chance to rekindle the magic of a long ago business when he and a group of private investors bought the Ladder Creek Helium Plant and Gathering system from DCP Midstream a year ago. Six months later, despite a bleak market and in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Tumbleweed reported it had quadrupled helium production at the plant near Cheyenne Wells, Colo., just west of the Kansas border.

That’s a far cry from the declining production the plant saw over the last 20 years. How Johnson and Tumbleweed achieved this is a long tale spanning decades and a lot of care to cultivate a resource that was never fully developed.

For his position,, Johnson wasn’t operating from a novice’s point of view. While he only became the owner and operator in December 2019, his familiarity with the plant and region stretches back to the 1990s.

“What got me interested in this deal? It ties in directly to my history with the plant,” Johnson told Hart Energy in an interview. “I really felt that this was an undeveloped resource. I was out here in the 1990s and designed and built this plant from 1997 to 1999 and operated it. I was very familiar with the helium resource that was out here.”

Even though he had not been associated with the plant since then, he kept an eye on its progress.

“In keeping up with the plant over the following 20 years, the resources were just never fully developed,” he said. “There are some reasons for that.”

A historical perspective

To understand why Johnson was so bullish on the plant, despite declining production, one needs to back up a bit and look at the how the market was developed in the 1990s. The plant was originally built by Union-Pacific Resources (UPR), which ran it and its gathering system as both the upstream and midstream company.

Johnson, who worked for the company at the time, said UPR’s investment during that time was based on more than just the gas. The gas in the region often contained 50% to 70% nitrogen.

“You could have 300 to 400 Btu, and you couldn’t even light a flare,” Johnson said. “It was considered ‘trash’ gas, and the wells were plugged.”

That was until someone, he said, got the bright idea to analyze the gas and found it also contained helium. That was enough to start the project.

“That’s basically how we ended up developing the project in the ’90s—going back to all of the historically plugged gas wells and bringing them online,” Johnson said. “There was a tremendous amount of resource here.”

Johnson was charged with designingand building it for UPR.

“We spent over $100 million building this plant in 1997,” he said. “In order to justify it, when we wrote contracts from the upstream side to the midstream side, those contracts were written to favor the plant. It was a right pocket, left pocket deal.”

All of that changed in 1998 after UPR’s failed hostile takeover bid for Pennzoil. After that, UPR acquired Canadian oil producer Norcen in a $3.5 billion deal. Johnson said the company did very little due diligence on the company and ended up taking a $1 billion write down a year later based on overestimated reserves.

Eventually, UPR ended up selling its upstream assets to Anadarko Petroleum and its midstream assets to Duke Energy Field Services.

“They split the baby and Anadarko had to live with the contract with Duke Energy, which wasn’t very good [because it was originally written to favor the midstream side of UPR.]”

At the time, Johnson said, the wells were getting a 10% to 15% rate of return.

“If you’re an upstream company, you’re deciding where to deploy your capital so you’re going to go drill better wells than that,” he said. “So the resource was just never developed.”

Johnson spent the last two decades watching from afar as the plant declined. It got a shot in the arm in 2005 when Duke Energy laid a pipeline into Kansas and picked up gas from the Bradshaw Field. Johnson said that gas was about 1% helium but continued to decline.

“That continued decline until 2019 is how it got to the point that I could purchase it,” he said.

Johnson knew the first thing he needed to do once the acquisition was made was to start rebuilding contracts with producers and explorers.

“Once we got in, we started pitching a different kind of contract structure with fixed wellhead pricing back to the producer,” he said.

He also knew each individual producer had a unique story to tell.

“Historically, a producer settlement statement from a midstream company is complicated,” Johnson said. “You have to look at every one of your components and what your percentage of each one is, what were the actual recoveries are in the plant and what were the commodity prices doing?”

The helium drive he put forward at the plant helped alleviate the month-to-month anguish of not knowing how much money the plant would get back from producers.

“In our case, with helium prices going the way they have, maybe 70% to 95% of the revenue comes from helium, and I’ve got long-term fixed contracts on helium prices,” Johnson said. “By having a fixed helium price, I can offer a producer a fixed wellhead price netback. And I’ll take the commodity risk on the hydrocarbon because it’s not a significant part of the revenue.”

That approach created what Johnson calls a “wave of interest.” Tumbleweed secured three new long-term gathering and processing agreements in the first half of the year and quadrupled production.

Two of the new agreements have more than doubled the plant’s inlet volume to 12 MMcf/d of natural gas, according to reports. The third contract was estimated to increase the production a further 3 to 5 MMcf/d.

Additionally, the increased output from the three agreements is expected to increase the daily helium output of the plant to more than 200,000 cf/d or about 65 MMcf/year.

Johnson also told Hart Energy that there are 13 different producers that are looking at prospecting and drilling inthe region.

“There’s over a 1,000 square miles of 3D seismic out here,” he said.

Helium demand

Before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, there was a worldwide shortage of helium of about 10%. The shortage at the moment is being filled by the Amarillo government supply, according to Johnson. The government’s supply may only last another three years, and efforts to privatize it are underway.

“There’s a lot of demand to find new helium sources,” Johnson said. “Obviously, it drove the price of helium up to where we are right now.”

In 2019 nongovernment users were paying $4.29 per cubic meter ($119.00 per thousand cubic feet). The pandemic has turned the undersupply into a small oversupply, but Johnson said that is due to the pandemic’s impact on the industries that need helium.

“Everyone expects it go right back to where it was to being in a shortage again, until new foreign sources can come online in the next few years,” he added.

Supply futures

One concern for the region is the recent change in the regulatory environment for drilling in Colorado. In September of this year, the state legislature passed a 2,000-ft. setback rule that makes obtaining drilling permits more difficult. However, the rule comes with “offramps” that will allow drillers to get as close as 500 ft to restricted buildings.

Will that affect the availability of supply to the Ladder Creek Helium Plant?

“We’re very in tune to the regulatory issues here in Colorado. We’re on the forefront of addressing that,” Johnson said.

As a midstream company, which of course doesn’t drill wells, Tumbleweed still pulled together a lot of information.

“Basically, we educate the Colorado Oil & Gas Commission on the kind of drilling we are doing out here,” Johnson said. “These wells are shallow, 5,000-ft vertical wells that don’t require fracking. They don’t require multiwell pads. They don’t require any of the quote-unquote bad things going on in the Denver area that has everybody so upset.”

The price of the wells is right, too. Johnson said they are half-a-million dollar wells to drill, which get drilled in about three to four days. They are low-environmental impact wells, he said.

For Johnson and Tumbleweed, it has been a refreshing run of success in a midstream industry that hasn’t seen a lot of positives lately.

Recommended Reading

Air Products Sees $15B Hydrogen, Energy Transition Project Backlog

2024-02-07 - Pennsylvania-headquartered Air Products has eight hydrogen projects underway and is targeting an IRR of more than 10%.

Humble Midstream II, Quantum Capital Form Partnership for Infrastructure Projects

2024-01-30 - Humble Midstream II Partners and Quantum Capital Group’s partnership will promote a focus on energy transition infrastructure.

BP Restructures, Reduces Executive Team to 10

2024-04-18 - BP said the organizational changes will reduce duplication and reporting line complexity.

Air Liquide Eyes More Investments as Backlog Grows to $4.8B

2024-02-22 - Air Liquide reported a net profit of €3.08 billion ($US3.33 billion) for 2023, up more than 11% compared to 2022.

NOV's AI, Edge Offerings Find Traction—Despite Crowded Field

2024-02-02 - NOV’s CEO Clay Williams is bullish on the company’s digital future, highlighting value-driven adoption of tech by customers.