(Source: HartEnergy.com, Shutterstock.com)

If it’s true that things will get a lot worse before they get better then we’re on the right track … because everything from the pandemic to the Saudi-Russian crude war to NGL prices is definitely worse.

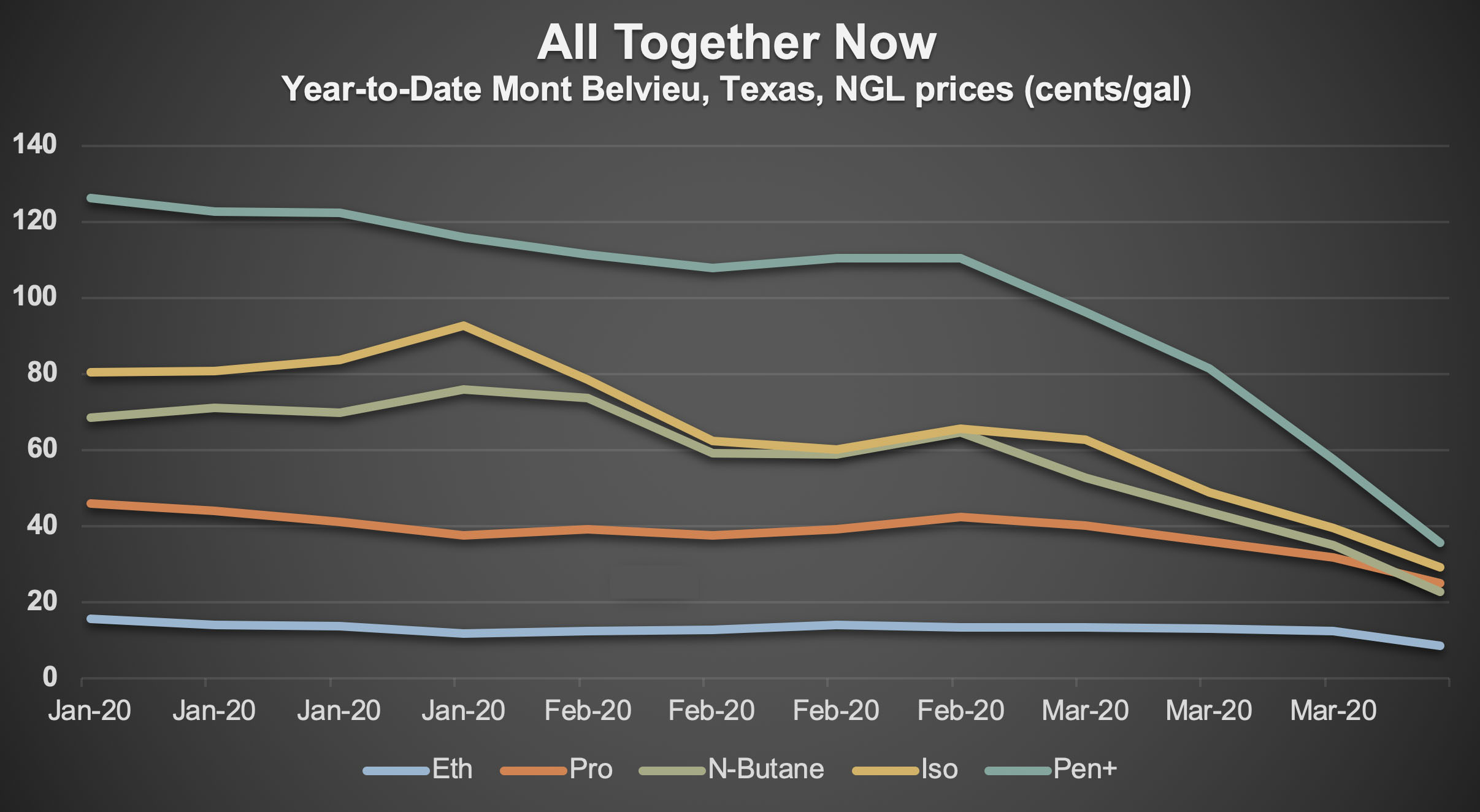

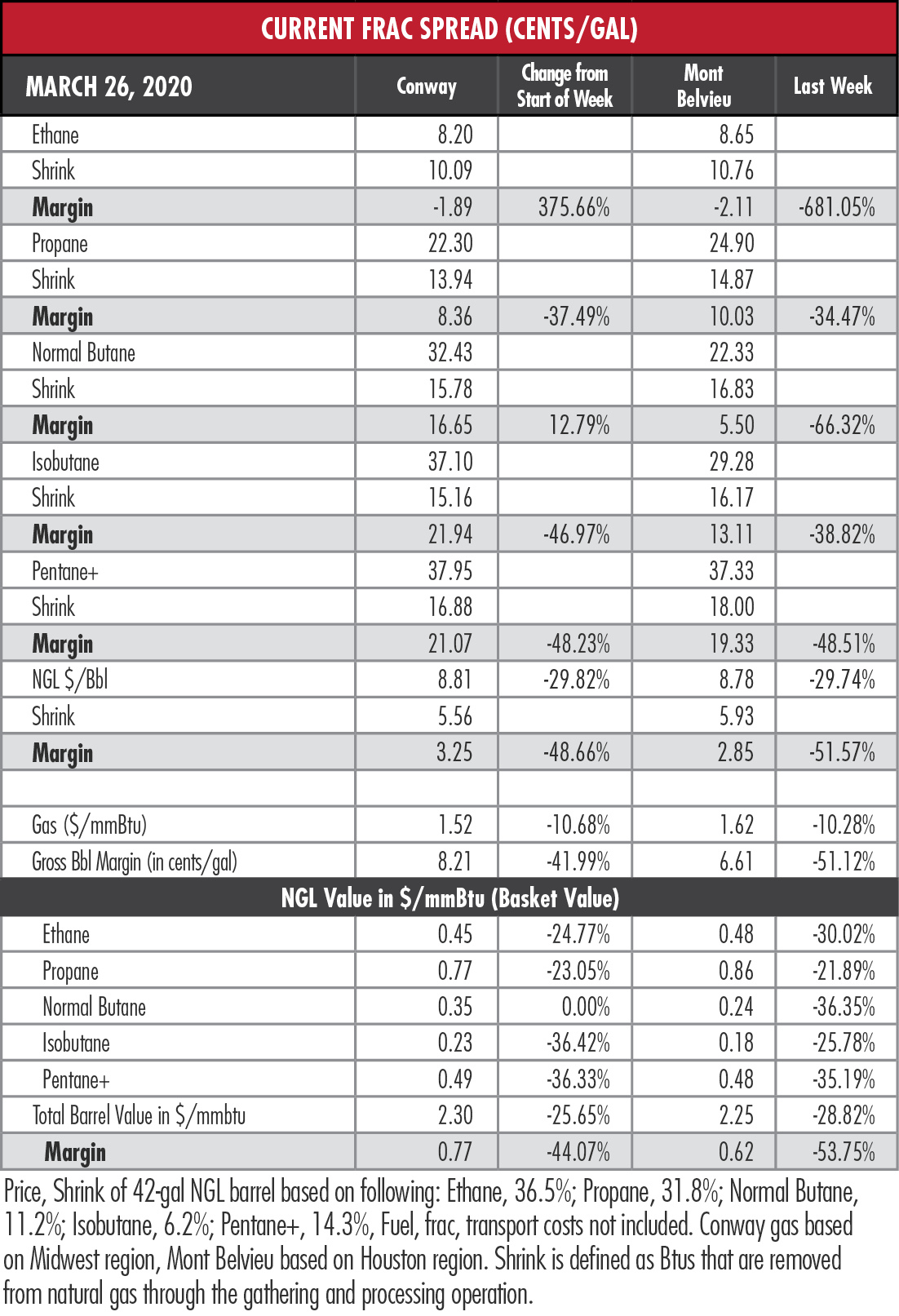

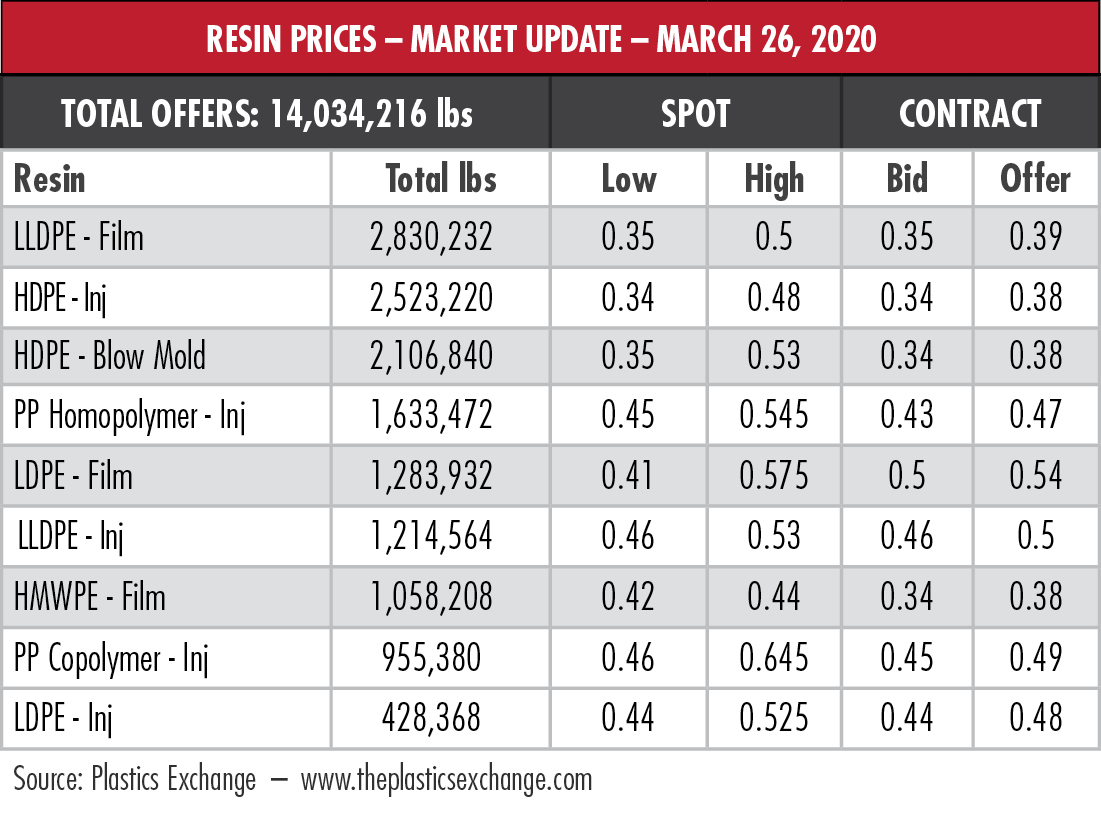

The Mont Belvieu, Texas, hypothetical NGL barrel continued its freefall last week, giving up 29.8% of the previous week’s record low value. The barrel’s price collapsed into single digits as all of its components recorded record lows for the 15 years that Hart Energy has tracked them.

Seemingly in defiance of the new social norms of physical distance, the Mont Belvieu five have collectively converged at around the same price, as traders wash their hands of NGL optimism.

“You’ve got this huge compression on NGL prices because when demand goes away, they’re all falling to the same point,” Peter Fasullo, co-founder and principal at EnVantage Inc., told Hart Energy. “If you have lower crude prices, you have lower naphtha prices. That harms the cracking economics for NGLs but especially for ethane. It harms the petrochemical industry’s low-cost position because if [foreign-produced] naphtha is a better feedstock in Europe and Asia, they’re not going to be using propane, they’re not going to be using ethane as much, or butanes.”

Weakness in NGL prices wreaks havoc up the value chain as well.

“With weak U.S. natural gas prices [famously negative at some hubs], some operators had been able to sustain operations because of the money made by production of associated liquids,” Mark Finley, fellow in energy and global oil at Rice University’s Baker Institute’s for Public Policy, told Hart Energy. Finley, as senior U.S. economist at BP Plc, formerly led production of the BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

“But with oil prices now falling fast, the economics of some of those operations may be called into question—impacting both oil and natural gas production,” he said.

Large volumes of U.S. natural gasoline are exported to Canada for use as a diluent for oil sand production, Fasullo said. But as crude prices have crashed, oil sands crude no longer makes economic sense.

“There is no arb to export propane and butane from here to Asia, or from here to Europe,” he said. “Then it becomes, do we close down our exports? We export 1.2 million barrels of propane, we export about 300,000 barrels a day of butane.”

So far, export numbers still look pretty good but only because the listings are based on last month’s margins.

“We’ve got negative margins to export right now when you include transportation costs,” Fasullo said. “You’ve got to start seeing LPG exports start to drop. Where does that go? It’s got to go into storage.”

And storage is already high. The U.S. Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) data show that ethane/ethylene inventory in December totaled 57.4 million barrels, or 15.2% higher than in December 2018. Propane/propylene for the week ending March 20 was up 25.7% over the same week in 2018. Butane/butylene was 5.2% higher for December over December 2018. Isobutane was up 31.2% in a year, and natural gasoline storage was essentially the same.

“That’s why you’re seeing these collapse in prices occur to the degree at which they are occurring,” Fasullo said. “That’s why you’re seeing natural gasoline that much over propane. That’s why you’re seeing ethane below propane. It’s because everything’s ending up in storage.”

In the week ended March 20, storage of natural gas in the Lower 48 experienced a decrease of 29 billion cubic feet, the EIA reported. The EIA figure resulted in a total of 2.005 trillion cubic feet (Tcf). That is 79.5% above the 1.117 Tcf figure at the same time in 2019 and 17% above the five-year average of 1.713 Tcf.

Recommended Reading

Marketed: Wasatch Energy Management Non-operated WI in Utah

2024-02-14 - Wasatch Energy Management has retained EnergyNet for the sale of non-operated working interest and royalty opportunities in Duchesne and Uintah counties, Utah.

Marketed: Stone Hill Minerals Holdings 95 Well Package in Colorado

2024-02-28 - Stone Hill Minerals Holdings has retained EnergyNet for the sale of a D-J Basin 95 well package in Weld County, Colorado.

Marketed: Navigation Powder River Eight Leasehold Lots in Wyoming

2024-04-09 - Navigation Powder River has retained EnergyNet for the sale of eight non-producing federal leasehold lots in Converse and Campbell counties, Wyoming.

Marketed: Amati Royalties Powder River Basin Opportunity

2024-03-01 - Amati Royalties has retained EnergyNet for the sale of a Powder River Basin opportunity with four wells and two pending wells in Campbell County, Wyoming.

TotalEnergies Entering, OMV Exiting SapuraOMV JV

2024-01-31 - TotalEnergies aims to deepen its presence in Malaysia through the $903 million deal to acquire OMV’s interest in the SapuraOMV Upstream joint venture.