Tim Duncan may lead one of the top U.S. Gulf of Mexico producers at Talos Energy Inc., but he refuses to let go of the “scrappy underdog” mentality that has guided his whole career.

Duncan started his petroleum engineering career in the lean 1990s at Pennzoil E&P before taking the risk to join a little-known startup, Zilkha Energy.

When the Gulf of Mexico was waning in popularity, Zilkha started a risky buying spree of seismic data and leases just as 3-D seismic technology was emerging, eventually ensuring much better success rates on drilling prospects.

The successful company sold in 1998 for more than $1 billion.

“This small company found its first-mover advantage. But you had to have the courage,” Duncan said. “I saw that as a young engineer, and it influenced me. I thought, ‘I’m just going to put that into my memory box and tap into it one day if I’m lucky enough to be in a position of influence’.”

The strategy, Duncan decided, was to stay nimble and take smart risks.

After working executive roles at a couple of other Gulf of Mexico startups that were sold, Duncan co-founded Talos in 2012—before turning 40 years old—with a Gulf focus when the rest of the industry was pivoting to the emerging tight oil boom onshore.

Duncan’s strategy led Talos into the newly opened offshore Mexico market, making the potentially groundbreaking Zama discovery in 2017.

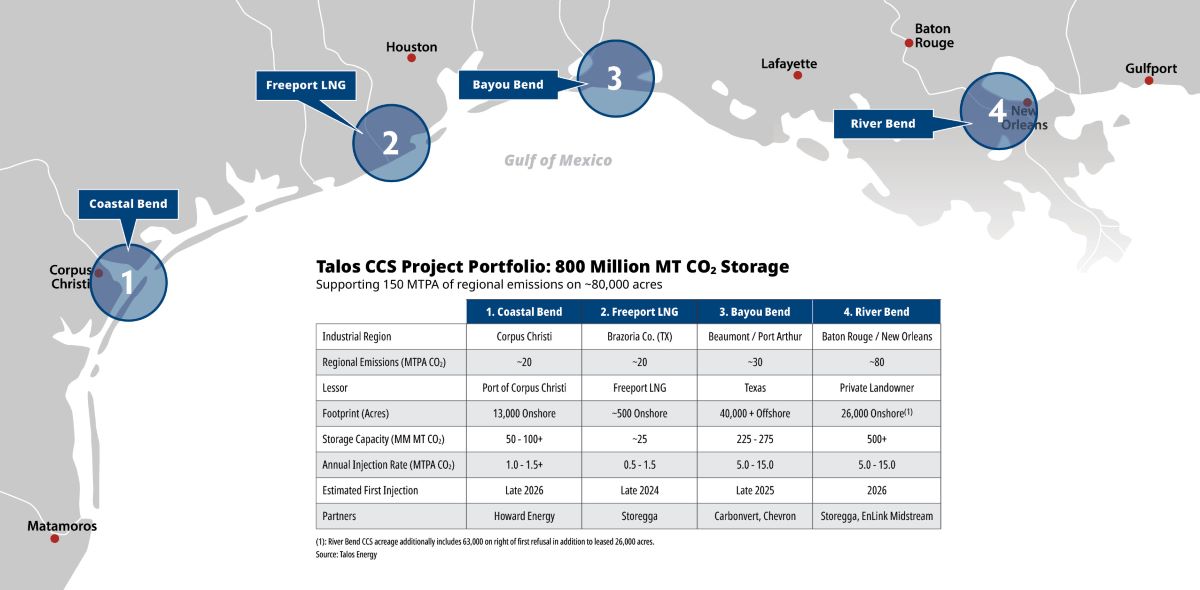

And, last year, Talos became a first mover—if you are noticing a pattern here—into the offshore carbon capture and storage (CCS) market in the shallow U.S. Gulf, buying up acreage for CCS hubs when the ongoing energy transition is focusing more on net-zero emission goals. Chevron Corp. recently became a 50% partner on Talos’ pioneering Bayou Bend CCS project offshore of the Texas-Louisiana border.

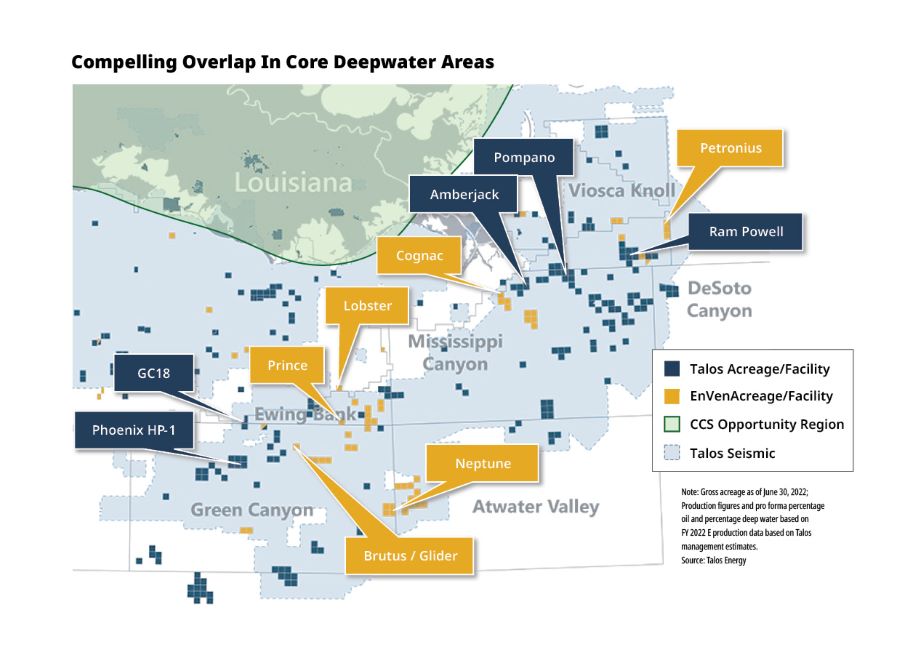

In the more traditional U.S. Gulf, Talos bought EnVen Energy for $1.1 billion to boost its output to nearly 90,000 boe/d. With the new acreage and volumes, Talos can challenge Hess Corp. and Murphy Oil Corp. as one of the top U.S. Gulf operators after the Gulf’s big four of Shell Plc, BP Plc, Chevron and Occidental Petroleum Corp. (Oxy). Almost 70% of total U.S. Gulf volumes come from the four biggest producers.

Talos is partnering more with those top deepwater players, including BP on the new Puma West project in the emerging subsalt Miocene exploration trend and an exploration joint venture with Oxy as well.

“More than any one particular prospect, we’re trying to unlock some trends in the Gulf,” Duncan said.

“The majors are still out here,” he added. “They’re not out here to buy old assets. They still think there’s enough good, new things to look for. We’ve become a more visible partner to the BPs and Chevrons and Oxys and Shells, and we’re proud of that, and we’re trying to see how we can expand those relationships.”

That zagging-when-the-industry-is-zigging approach could soon pay off with shale productivity either at or near its peak, said Leo Mariani, senior energy analyst at MKM Partners.

“You’re going to see some degradation in shale quality, so you want to see a robust inventory in offshore projects,” Mariani said. “I don’t want to say shale is boring, but it’s kind of repetitive. Talos is a company with a lot happening.

“For a small company, Talos has proven to be a very effective operator,” he added.

Offshore beginnings

Duncan was born in 1973 in New Orleans while his father worked for Amoco. They moved frequently and around the world, from Texas to Egypt.

“I kind of grew up enamored by big offshore projects all over the world,” Duncan said.

With the oil and gas industry in shambles at the end of the 1980s, Duncan still opted to major in petroleum engineering at Mississippi State University—another place that helped shape his underdog mentality similar to the recently deceased MSU football coach Mike Leach and his quirky, pirate-loving, air-raid style.

“We felt like ‘the other guys,’ if you will, compared to the bigger programs,” Duncan said. “It was that scrappy, hard-working attitude.”

After Zilkha, Duncan was recruited to join the private equity-backed startup Gryphon Exploration that wanted to replicate Zilkha’s success. Gryphon was sold in 2005 to Woodside Energy.

“It was pure exploration. Most of what we found was underneath existing oil fields,” he said.

He then co-founded Phoenix Exploration in 2006, which was sold in 2011 to a group led by Apache Corp.

Leaning on much of the same management team he had worked with, Duncan took over the president and CEO titles for the first time when founding Talos with support from Apollo Global Management and Riverstone Holdings.

He took the contrarian approach to stick with what he knew.

“It’s 2012. Why are you still out here? Everyone is onshore,” Duncan said. “But there’s going to be less competition for assets.”

The goal was to buy up acreage and lease areas in relatively mature areas and explore nearby. And, using that same mentality, Talos has moved to increasingly deeper depths.

“We’ll keep exploring, but we’ll use other companies’ platforms and infrastructure,” he said. “We believed in improving seismic technology. Computing speeds were changing everything. Rig technology, mud technology [and] subsea technology. All of those things were going to be in our favor to be an independent that can grow the company in deep water using the same shallow-water principles.”

There was a fear though with all the money moving onshore. “How were we going to get out of it? What if there weren’t functioning capital markets?” After all, all of his previous companies were founded and sold.

Then came the oil downturn in 2015 and 2016, and those fears were realized. The capital was largely gone.

The solution: Rather than sell, Talos opted to go public by entering into a reverse merger in 2017 with Stone Energy Corp.

“That changed the dynamic,” Duncan said.

He was so determined, he said, that he was negotiating the Stone deal while his family evacuated his Houston-area home that was severely flooded during Hurricane Harvey.

“It kind of changes your perspective when you lose everything you own,” he said. “It kind of defines your before and after.”

Crossing the nautical border

Prior to the Stone deal, the government in Mexico had enacted energy reforms to open its oil and gas sector to international investment for the first time in nearly 80 years.

Major companies nervously eyed the Mexican side of the Gulf to see if the reforms would stick.

With the idea of going public, Duncan said, Talos had to think bigger.

“Should we be thinking about international? How do we cast a wider net? How do we get more people interested in our story?” Duncan said. “We saw what was happening in Mexico with opening up the energy sector, and we decided to bid because we didn’t think anybody would pay attention to us.”

In this case, being smaller and nimbler helped. Talos led a consortium to make the shallow-water Zama discovery in 2017, which was considered potentially the biggest global find of the year.

“It was about taking what we’re good at and trying to lean into something different,” Duncan said. “If we were successful, then we could differentiate ourselves.”

And they proved they could do it. The plan was to work with state-owned Pemex, reach a final investment decision (FID) by the end of 2020 and achieve first oil right around now.

However, politics intervened.

The goal now is to reach FID by late 2023 at the earliest.

What happened is that Andrés Manuel López Obrador, known as AMLO, succeeded Enrique Nieto as the president of Mexico in late 2018 and sought to roll back some of the energy reforms.

Talos was essentially forced to hand over operatorship to Pemex and to reduce its 35% operating interest in Zama down to a participating 17.35% stake.

“We knew there was a reasonable likelihood, although we disagreed with it, that they would pick Pemex to be operator,” Duncan said. “Once they did, we weren’t going to change that, but we needed to stand up for our efforts and the value of the asset.”

However, since Talos led the appraisal, discovery and FEED work, Duncan managed a pivot: The goal now is to still play a significant role in an integrated project team that is still being negotiated.

“We’ve fine-tuned a strategy on how to make money in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico, but we also think we can expand that into new business opportunities that really differentiate who we are as a public energy company.” – Tim Duncan

“Our hope is somewhere in the first quarter we’ll be able to put in the final development plans and talk about final commercial arrangements with Pemex,” Duncan said. “Then this thing finally gets to FID by the end of 2023.”

Fernando Zavala, Pickering Energy Partners vice president, said Talos took a hit from the political changes but that most of the bad news is now done. Hopefully, all the parties can move forward amicably this year.

“That really was just a very unfortunate chain of events for them. That’s just the risk of dealing with the Mexican government,” Zavala said, joking that he can say that because he is a native of Mexico.

But would Talos ever look to sell its Zama position?

“There’s no reason for us to think about that until we can get this project down a glide path of being financeable and getting to a final investment decision,” Duncan said.

“The story is still being written,” he added. “The bottom line is it’s still one of the biggest discoveries in the history of the country, and that was us.”

Embracing the transition

Despite some of the political hiccups, Talos was riding high in 2019, after the big discovery and going public.

At the end of the year, the company scaled up and bought a portfolio of producing U.S. Gulf assets and acreage from ILX Holdings, Castex Energy and Venari Resources for $640 million.

“We’re going into 2020 feeling pretty damn good. And, here comes the pandemic, and everything falls apart,” Duncan said with a resigned laugh.

Talos had a strong enough balance sheet to survive the temporary crash in demand, but many companies did not. With investor sentiment already pushing for more financial conservatism and greater shareholder returns in 2019, that trend continued even stronger after 2020.

“We knew we weren’t going to be ready to do ‘returning capital to shareholders’ as a small company coming out of the pandemic,” Duncan said.

So, with the investment community focusing on dividends and emerging ESG trends, Talos ultimately decided to pursue CCS projects, especially with the Biden administration focusing on the energy transition.

“The idea was what can we do on the low-carbon side?” Duncan said. “CCS springs up, and we said, ‘Hey, this is just about putting together land positions.’”

Talos focused on marshy areas in southern Texas and Louisiana—both onshore and offshore—with good geology and proximity to industrial emitters. “We decided to lean in and chase it.”

That land race all happened very quickly, starting in 2021. And it seemed on the verge of paying off in 2022, with the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) expanding tax credits for both carbon capture projects and restoring deepwater lease sales after Biden had initially implemented a moratorium. After all, Talos was one of most active bidders in lease sale 257, with high bids on 10 blocks totaling 57,000 gross acres.

“We were one of the few public companies that benefited from multiple parts of the IRA,” Duncan said.

The main Bayou Bend CCS project has more than 40,000 acres offshore and the potential to hold roughly 250 million metric tons of CO2. Apart from initial partner Carbonvert, Chevron signed on in May. Duncan acknowledged Chevron buying in gave Talos “legitimacy” in the burgeoning CCS industry.

“They could easily compete against us, but they saw more value in partnering with us,” Duncan said of Chevron. “Everything they do is thoughtful and highly engineered, and they are fully committed to the space. So, it brought a tremendous amount of validation.”

The next challenge is getting all the emitters—the refiners, chemical plants, LNG hubs and more—to invest in technology to capture their CO2, Duncan said. Talos can then transport and permanently sequester the carbon for a negotiated tolling fee.

Nate Pendleton, energy analyst and vice president at Stifel, said Talos’ CCS projects are “economic today” with the tax credits.

“We’re really bullish on the fundamentals of CCS, and it’s needed to meet climate goals,” said Pendleton, who is particularly high on the Bayou Bend CCS project. “I would offer that offshore has less risk for CCS than onshore. It’s mostly not drinking water, and it’s located away from communities.

“When Talos saw the opportunity, they were able to jump on it before the majors were able to go through their processes,” Pendleton said.

Big picture

Talos is well-positioned for a strong 2023, even if the CCS projects will not come online for another three years, Pendleton said.

The company’s other CCS projects are its onshore River Bend project near the Mississippi River in Louisiana, the Coastal Bend project near the Port of Corpus Christi and an emissions-source project near Freeport LNG in Texas.

In the meantime, Talos is focused on its “high-impact” drilling prospects like Puma West, Duncan said, and its more “middle-market,” subsea-tieback prospects near existing infrastructure, including its Venice, Lime Rock and Rigolets ventures, all of which are underway. Talos also is drilling its Mount Hunter prospect from the Pompano platform.

Other acquisitions and potential international expansions remain possible, Duncan said.

“We’ve looked down in South America and West Africa in the past 12 to 15 months and looked in a significant way,” Duncan said, confirming that they are “still” looking. “We’ve looked at M&A hard since the pandemic knowing that we can impact synergies and impact things quicker in the Gulf of Mexico but, long term, knowing that outside of the Gulf of Mexico might need to be in the portfolio.”

Duncan definitely does not want to rule out any additional nimble, smart bets. He remembers his early lessons in the industry.

“We’ve fine-tuned a strategy on how to make money in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico, but we also think we can expand that into new business opportunities that really differentiate who we are as a public energy company,” he said.

Recommended Reading

Range Resources Holds Production Steady in 1Q 2024

2024-04-24 - NGLs are providing a boost for Range Resources as the company waits for natural gas demand to rebound.

Hess Midstream Increases Class A Distribution

2024-04-24 - Hess Midstream has increased its quarterly distribution per Class A share by approximately 45% since the first quarter of 2021.

Baker Hughes Awarded Saudi Pipeline Technology Contract

2024-04-23 - Baker Hughes will supply centrifugal compressors for Saudi Arabia’s new pipeline system, which aims to increase gas distribution across the kingdom and reduce carbon emissions

PrairieSky Adds $6.4MM in Mannville Royalty Interests, Reduces Debt

2024-04-23 - PrairieSky Royalty said the acquisition was funded with excess earnings from the CA$83 million (US$60.75 million) generated from operations.

Equitrans Midstream Announces Quarterly Dividends

2024-04-23 - Equitrans' dividends will be paid on May 15 to all applicable ETRN shareholders of record at the close of business on May 7.