If Plug Power CEO Andy Marsh worked for the U.S. Department of Energy and had a magic wand, he said he would use the entire $9 billion—set aside to create hydrogen hubs—on converting pipelines.

“That’s where the cost is and that’s what we really have to address,” Marsh said during a recent hydrogen conference in Houston.

The U.S. hydrogen sector has been celebrating wins lately as the Biden administration looks to lower emissions. The Inflation Reduction Act is making clean hydrogen economical with its 10-year production tax credit for up of $3/kg among other incentives.

For the emerging hydrogen industry to further improve costs and have a chance at decarbonizing various sectors, however, a massive infrastructure buildout is needed, experts say. Many believe using existing pipelines and blending hydrogen with natural gas is a key starting point but pipelines dedicated to pure hydrogen are essential for deep decarbonization. Getting there is possible, they say, but it will require overcoming regulatory challenges, gaining public acceptance and time.

“Building these networks out is important. Transporting hydrogen is equally important.”—Andy Marsh, Plug Power

Companies like Plug Power, which develops hydrogen fuel cell systems and produces green hydrogen, is filling the pipeline with projects as it grows a national network of plants in New York, Tennessee, Georgia, California, Texas and Louisiana alongside other parts of the U.S.

“Building these networks out is important. Transporting hydrogen is equally important,” Marsh said. “It’s expensive to transport hydrogen. It’s 33 kilowatt hours of energy in a kilogram of hydrogen, and to move that about 500 miles, it’s about a buck in liquid form. To get our costs right, we need hydrogen pipelines in this country and in Europe. Cost for a dedicated pipeline, say from putting hydrogen from Wyoming to California where the wind’s blowing and where they need it, is probably about $0.10 a kilogram.”

Achievable goals

Efforts are underway to build pipelines for hydrogen as tests are being carried out on hydrogen blending. Some parts of the U.S. such as Texas are further ahead of others, already having established a hydrogen economy on which to build.

Hydrogen has gone from being talked about as niche power generation with fuel cells and vehicle fuel to hydrogen at grid scale and long-duration energy storage, said Brian Weeks, senior director of business development research operations for GTI Energy.

“The best way to move large volumes of energy is in a pipeline,” Weeks said.

Along the Gulf Coast region, there are about 1,500 miles of existing hydrogen pipeline. That pales in comparison to the 300,000 miles of high-pressure transmission natural gas pipelines and an additional 3 million miles of lower pressure distribution, natural gas pipeline systems, he said were in the U.S.

“It’s not like we can immediately start moving hydrogen in the natural gas pipeline system today, but we do know that the end goal is very achievable.”—Brian Weeks, GTI Energy

Though hydrogen can be transported in liquid form in tanks on trailer trucks, existing pipelines are seen as a low-cost option for transporting large quantities of hydrogen, given high capital costs and other initial risks associated with new pipelines.

“It’s not like we can immediately start moving hydrogen in the natural gas pipeline system today,” Weeks said, “but we do know that the end goal is very achievable.”

Research has shown that few changes are needed to existing natural gas transmission or distribution pipeline networks if the hydrogen blend is low.

Blending benefits

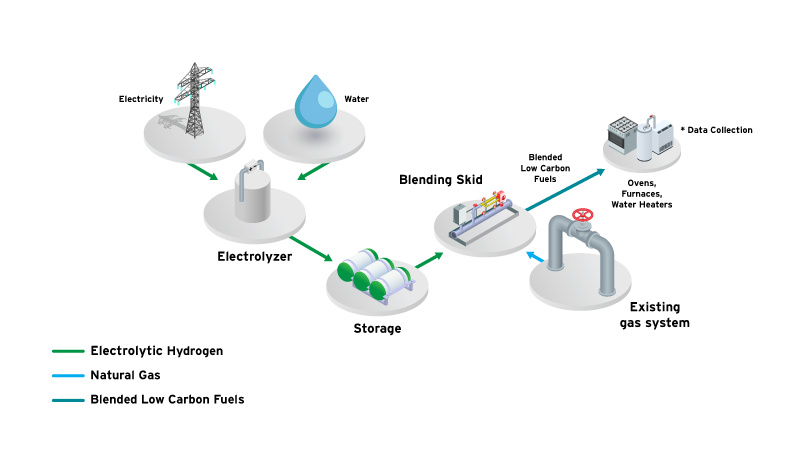

Southern California Gas Co. (SoCalGas) has been evaluating hydrogen blending, including at its training facility called Situation Village.

In this make-believe village, the company studies the impacts of hydrogen blending on equipment such as home appliances and pipes. Engineered leaks test the leak detection equipment and employees’ response to ensure “we’re doing all the same things that we would in the natural gas system, operating safely and doing the normal maintenance and integrity tests,” said Neil Navin, vice president of clean energy innovations for SoCalGas.

The company has implemented several hydrogen blending demonstration projects. Its latest project, announced in September, aims to demonstrate how electrolytic hydrogen can be safely blended into existing natural gas infrastructure on the campus of the University of California, Irvine.

“There’s really no need to modify most equipment,” Navin said, but certainty is needed when you get to 20%. “So, we need to test it along the way.”

Hydrogen blending above 20% increase the chance of permeating certain pipes, raising the chance of leaks and embrittlement.

“But we do feel that given the size of our system and the ability to absorb a significant amount of blended hydrogen, it actually provides an opportunity for the market before you have pure hydrogen pipelines,” Navin said, noting the latter will be needed to move hydrogen to end users.

Dedicating pipelines

“Deep decarbonization” of the entire economy requires moving larger volumes of hydrogen, and there is value in moving pure hydrogen rather than blending it, according to Navin.

“You don’t want to have to unscramble the egg every time you want to get your hydrogen,” he said. “We firmly believe that some amount of hydrogen backbone will start to emerge in the United States.”

SoCalGas has proposed developing what would be the nation’s largest green hydrogen infrastructure system. Called the Angeles Link, the system would move large quantities of hydrogen via a new pipeline system into the LA Basin from solar- and wind-rich areas. Hopes are to lower emissions from electric generation, industrial processes, heavy-duty trucks and other sectors.

“A regulatory iron curtain has descended across the Appalachian Mountains. So new gas infrastructure is impossible. I think that hydrogen infrastructure will be equally difficult.”—Mark Webb, Dominion Energy

Projects like Angeles Link, which awaits regulatory approval, could run into the billions of dollars and take years to complete.

Gaining the blessing of regulators and society add another layer of complexity.

Depending on the location, regulations could be an issue for hydrogen pipelines, according to Mark Webb, chief innovation officer and senior vice president for Dominion Energy. On the East Coast, where there is a need for natural gas, “a regulatory iron curtain has descended across the Appalachian Mountains. So new gas infrastructure is impossible,” he said. “I think that hydrogen infrastructure will be equally difficult.”

This could result in the emergence of regions where hydrogen production and delivery are localized.

Getting buy-in

Regardless of whether authorities are local, state or federal, regulatory permitting regimes that allow pipeline buildouts are essential to advancing hydrogen at scale.

“You’re going to have to figure out a way to use the existing right of ways for hydrogen. A lot of those rights-of-way agreements today either specify natural gas or they specify gas without designation,” Navin said. “Communities are not necessarily going to want to permit, especially in urban communities, new pipelines routes. … We need to figure out how do we reuse the existing infrastructure corridors today and use hydrogen.”

“You don’t want to have to unscramble the egg every time you want to get your hydrogen. We firmly believe that some amount of hydrogen backbone will start to emerge in the United States.”—Neil Navin, SoCalGas

Getting public acceptance and educating the public on safeguards—similar to steps taken after the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in Pennsylvania—are also critical, Webb added. Replicating natural gas systems with pipelines running through streets likely won’t happen for hydrogen other than in blended form, he said.

Hydrogen pipelines have been operated safely by a small number of companies in the U.S. to date; however, as the industry expands with more facilities and more people, safety should be paramount from the beginning.

“Just one or two incidents can lead to a lack of public support,” Webb said. “Regulatory will be your least concern if you don’t have public acceptance and buy-in.”

Recommended Reading

Defeating the ‘Four Horsemen’ of Flow Assurance

2024-04-18 - Service companies combine processes and techniques to mitigate the impact of paraffin, asphaltenes, hydrates and scale on production—and keep the cash flowing.

Tech Trends: AI Increasing Data Center Demand for Energy

2024-04-16 - In this month’s Tech Trends, new technologies equipped with artificial intelligence take the forefront, as they assist with safety and seismic fault detection. Also, independent contractor Stena Drilling begins upgrades for their Evolution drillship.

AVEVA: Immersive Tech, Augmented Reality and What’s New in the Cloud

2024-04-15 - Rob McGreevy, AVEVA’s chief product officer, talks about technology advancements that give employees on the job training without any of the risks.

Lift-off: How AI is Boosting Field and Employee Productivity

2024-04-12 - From data extraction to well optimization, the oil and gas industry embraces AI.

AI Poised to Break Out of its Oilfield Niche

2024-04-11 - At the AI in Oil & Gas Conference in Houston, experts talked up the benefits artificial intelligence can provide to the downstream, midstream and upstream sectors, while assuring the audience humans will still run the show.