Russia’s cutoff of natural gas to Poland and Bulgaria will have little immediate impact. (Source: FOTOGRIN/Shutterstock.com)

Russia’s cutoff of natural gas to Poland and Bulgaria was a relatively low-risk way for President Vladimir Putin to punish adversaries with minimal short-term impact, an expert on European natural gas geopolitics told Hart Energy on April 27.

An expansion of the disruption to include the rest of Europe, on the other hand, would have huge implications and necessitate a large-scale response, according to Anna Mikulska, a nonresident fellow in energy studies at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

The countries singled out had already been moving toward alternatives to Russian energy and their contracts with Russian gas giant Gazprom were set to expire in early 2023, Mikulska said. The reason given to halt shipments—that the countries refused to pay in rubles—could apply to any customer because no member of the European Union has agreed to pay for Russian energy directly with rubles.

NATO members Poland and Bulgaria are among those supporting Ukraine that have been designated “unfriendly” by Putin and therefore obligated to pay for natural gas shipments in rubles.

Demanding payment in rubles is likely a breach of contract, Mikulska noted. Bulgarian Energy Minister Alexander Nikolov alluded to that as well on April 27 when he accused Gazprom of using natural gas as a political and economic weapon in Russia’s war against Ukraine.

Traders have generally steered clear of rubles in the wake of sanctions against Russia. While the currency has rebounded on the Moscow exchange to the pre-war level of about 1.3 cents, Bloomberg reported that some strategists are leery of that rally because of Russian capital controls.

Unreliable partner

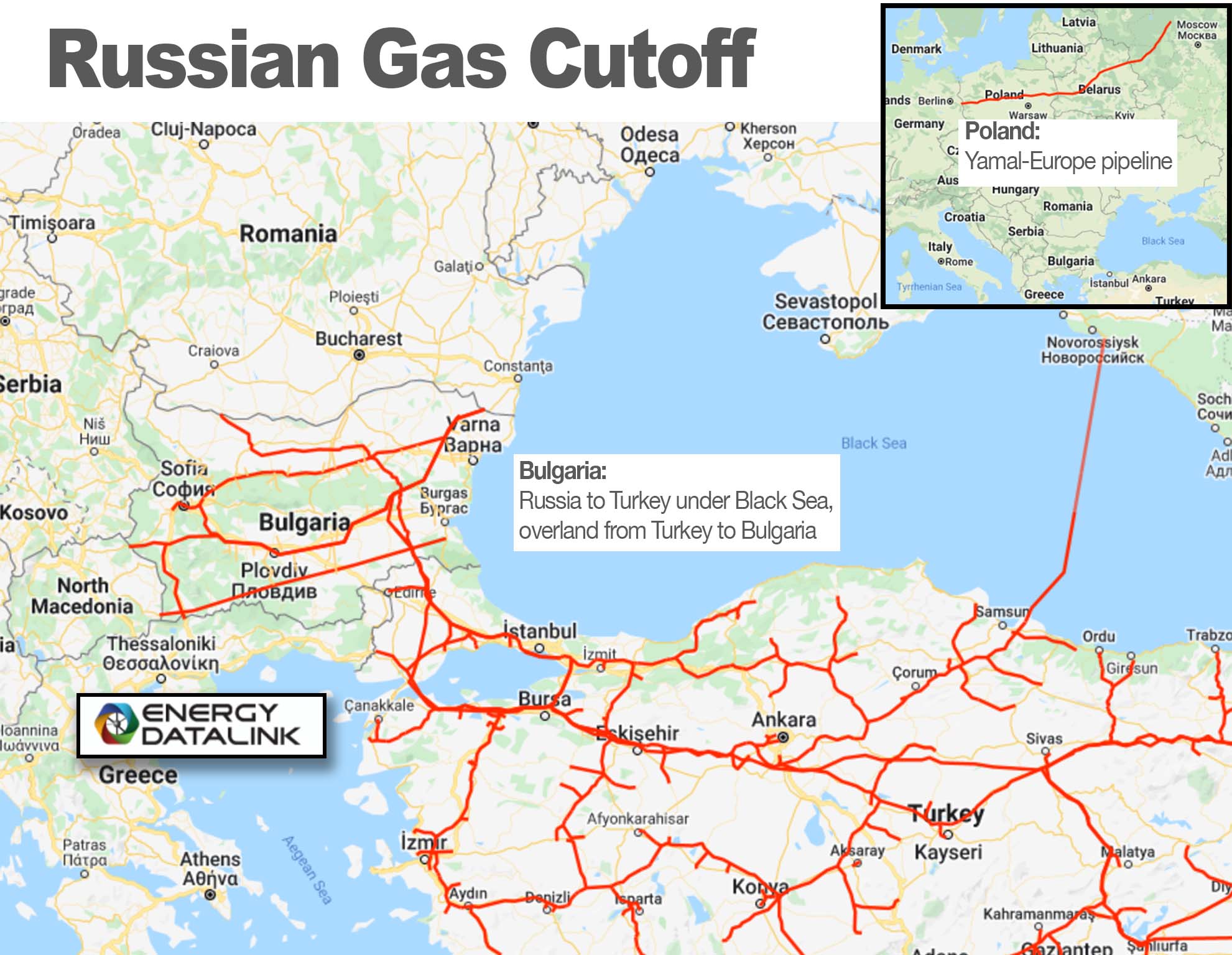

Russian natural gas is transported by the Yamal-Europe pipeline through Poland to Germany, where it is moved to other European countries on other pipes. Russian gas shipped to Bulgaria is transported under the Black Sea to Turkey, then pipelined the rest of the way by land.

Depriving a country of gas is as simple as cutting the pressure on the line. That would put the onus on a country like Poland if it chose to siphon gas at the expense of Germany and other European countries further down the line. It is not a new tactic.

“When Russia cut off gas to Ukraine in 2008-2009, they basically decreased the pressure on that transit route,” Mikulska said. Ukraine responded by siphoning gas during a cold winter and other countries suffered serious shortages.

The risk of Russia labeled an untrustworthy business partner is minimal, she said, because many in Europe, particularly Poland, have maintained that for years. The invasion of Ukraine and subsequent assaults on civilian populations also make clear that Putin is not really concerned with any accusations, including that he is an unreliable supplier of natural gas.

‘Gaslift’

However, Putin’s unpredictable nature means that a total disruption of Russian gas shipments to Europe is a real possibility, even if it defies economic and political sense. The invasion of Ukraine itself is a prime example of that thought process. Mikulska admitted that, four days prior to the invasion, she did not believe it would happen.

One solution to a complete disruption of Russian gas could be an updated form of the Berlin Airlift in 1948-1949. In a February white paper, Mikulska and Baker Institute colleagues Gabriel Collins, Kenneth B. Medlock III and Steven Miles propose a “gaslift” to exploit the U.S. LNG advantage and ease the impact of a potential cutoff.

The authors acknowledge a number of constraints, including insufficient nameplate capacity of European regasification facilities. Another challenge is the location of the LNG import terminals. Many are in southern regions and the Iberian Peninsula, with limited connectivity to the rest of the continent.

The authors suggest LNG surges at terminals in northern and western Europe, in which some plants would be pushed to exceed their capacity for a time. Another part of the solution, suggested by Collins and Miles in a subsequent paper, is the chartering of eight to 10 FSRUs to provide added offshore regasification capacity.

Recommended Reading

For Sale, Again: Oily Northern Midland’s HighPeak Energy

2024-03-08 - The E&P is looking to hitch a ride on heated, renewed Permian Basin M&A.

Gibson, SOGDC to Develop Oil, Gas Facilities at Industrial Park in Malaysia

2024-02-14 - Sabah Oil & Gas Development Corp. says its collaboration with Gibson Shipbrokers will unlock energy availability for domestic and international markets.

E&P Highlights: Feb. 16, 2024

2024-02-19 - From the mobile offshore production unit arriving at the Nong Yao Field offshore Thailand to approval for the Castorone vessel to resume operations, below is a compilation of the latest headlines in the E&P space.

E&P Highlights: Feb. 26, 2024

2024-02-26 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including interest in some projects changing hands and new contract awards.

CEO: Continental Adds Midland Basin Acreage, Explores Woodford, Barnett

2024-04-11 - Continental Resources is adding leases in Midland and Ector counties, Texas, as the private E&P hunts for drilling locations to explore. Continental is also testing deeper Barnett and Woodford intervals across its Permian footprint, CEO Doug Lawler said in an exclusive interview.