Over the next decade, oil and gas activity in the Appalachian Basin will be strongly driven by available takeaway capacity and pipeline expansion. (Source: DenPhotos/Shutterstock.com)

Presented by:

Editor's note: This article originally appeared in the April issue of E&P Plus.

Subscribe to the digital publication here.

Over the second half of 2020, Henry Hub prices rallied from depths of pandemic lows, with the 12-month strip reaching the $3/MMBtu range for the first time since early 2019. But in Appalachia, the next two years will look very different from the last five, when consistent pipeline capacity additions facilitated average production growth of 3 Bcf/d annually. Now, with only one takeaway project under construction, subtler differences in midstream connectivity will drive which producers and gathering systems can access these higher prices outside the basin and which ones will be left to compete for limited in-region demand.

In short, the competition is set. So who will capitalize and tap higher Henry Hub prices this year?

Serving in-region demand

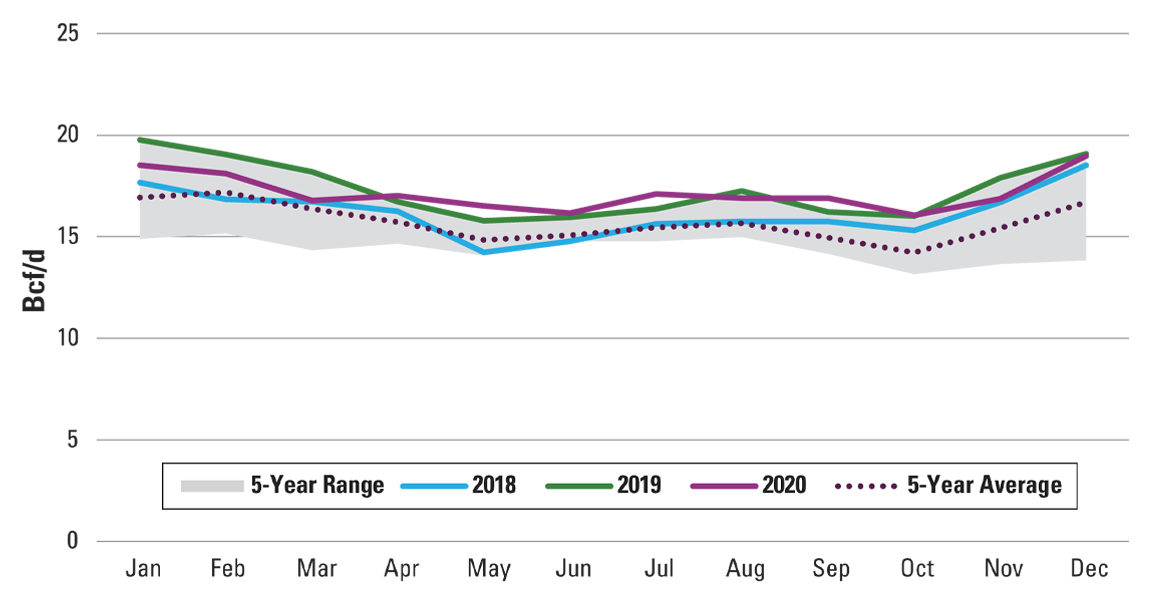

Demand in the Northeast, net of storage injections and withdrawals, averages ~17 Bcf/d annually but with ~3 Bcf/d of swing between the peak in February and low in October (Figure 1). Seasonally weak U.S. Northeast demand triggered ~2 Bcf/d of shut-ins last fall.

The lowest-cost acreage or best-capitalized producers are most able to serve Northeast demand, as in-region prices deteriorate with growing production causing marginal production to be priced out. Among operators with at least 50 wells put to sales since 2019, Chesapeake, Cabot, National Fuel Gas and Range Resources feature the lowest breakevens, while Cabot is the least levered of the public E&Ps. Major gathering systems positioned for growth include Williams’ Susquehanna Supply Hub, Williams’ Bradford Supply Hub, National Fuel Gas’s Clermont Gathering, CNX’s McQuay Area System and Equitrans’ legacy Equitrans Gathering.

Northeast takeaway capacity

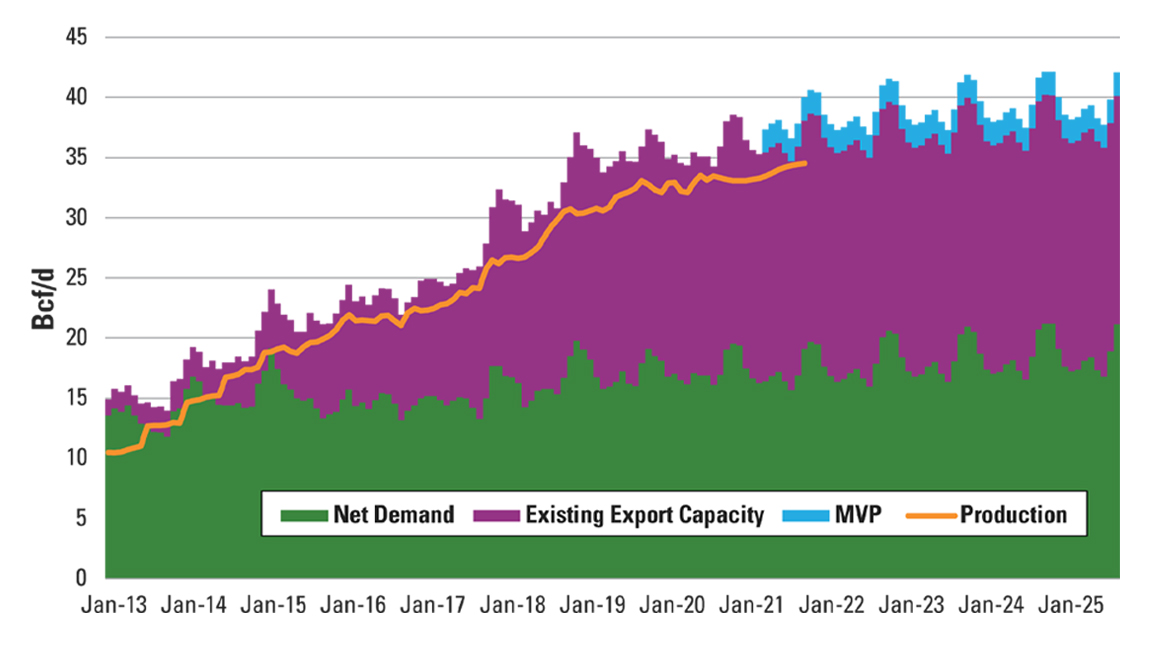

Most Northeast production does not stay in the Northeast, though. Takeaway capacity from the Northeast to other regions currently totals ~19 Bcf/d, growing as high as 21 Bcf/d once Mountain Valley Pipeline is completed.

The existing 19 Bcf/d of takeaway combined with the ~17 Bcf/d of in-region demand more than accommodates peak Northeast production of ~35 Bcf/d. However, last fall points to a possible future for Appalachian basis differentials, as in-basin prices collapsed to ~$1/MMBtu, despite ~1 Bcf/d of nominally available takeaway capacity. This disconnect reflects disparities in which gas can access this open capacity. Three routes—Tennessee Gas Pipeline (TGP) Zone 4, NEXUS and Rover—account for almost all of this available takeaway (Figure 2).

Implications for growth

Operators with the right midstream connections to available takeaway capacity have more sustainable growth options. In particular, these three pipelines mostly access Ohio volumes, so this acreage looks better positioned than acreage in Pennsylvania or the West Virginia panhandle with lower wellhead breakevens.

From 2014 to 2016, EQT (then a combined upstream, midstream and utility company) developed the Ohio Valley Connector expansion on its Equitrans Transmission system, taking West Virginia and Pennsylvania production to its Clarington, Ohio, interconnect with Rockies Express Pipeline and later with Rover. With difficult terrain in the Appalachian mountains around the Ohio River Valley, the project included only 50 miles of newbuild or looped pipe but a tariff rate of $0.30/MMBtu. Economics for pipeline expansions are often more favorable than for newbuild, but lining up commitments and building such a project would take at least three years.

Instead, intra-Appalachia basis spreads look likely to bring rigs back in Ohio and West Virginia in addition to Tier 1 Marcellus acreage, despite a ~$0.25/MMBtu difference in wellhead breakevens.

Since the beginning of 2019, Ascent and Gulfport drilled the most wells in the Utica South Dry Gas sub-plays. Of gathering systems, Energy Transfer’s Ohio River System, Equitrans’ Olympus Belmont Area, MarkWest’s Ohio Gathering System, Antero Midstream’s Utica Shale and Antero Midstream’s Marcellus Shale feature less attractive wellhead breakevens versus the best systems in Pennsylvania but are better positioned for immediate growth due to advantageous connections to interstate takeaway.

In terms of transmission, the most attractive piece of unsold long-term capacity is the ~150 MMcf/d of NEXUS capacity that can source gas in core southwest Pennsylvania acreage via a TETCO capacity lease. However, the balance of unsold NEXUS capacity, with receipts at the Kensington processing plant for rich-gas Ohio production with ~$4/MMBtu breakevens, is unlikely to sell until a supply header project is built or NGL prices skyrocket.

Rover accesses lower-cost Ohio supply relative to NEXUS; therefore, we expect Rover to sell out of its long-term capacity before NEXUS does. On TGP, current flows exceed producers’ contract capacity, but several consumers and marketers also contracted for capacity with receipts in northern Ohio. Filling this takeaway capacity may require upstream pipeline expansion.

Without question, the road map has changed in Appalachia. Whereas the last 10 years were marked by a race to prove up acreage and develop long-haul transmission, the next 10 years will be driven by existing infrastructure. Those upstream and midstream operators with the right connections and right-of-way stand to benefit from the higher Henry Hub prices in 2021 and 2022.

About the author:

Amber McCullagh is a director with Enverus and leads the company’s Midstream Intelligence team.

Recommended Reading

Well Logging Could Get a Makeover

2024-02-27 - Aramco’s KASHF robot, expected to deploy in 2025, will be able to operate in both vertical and horizontal segments of wellbores.

Tech Trends: Halliburton’s Carbon Capturing Cement Solution

2024-02-20 - Halliburton’s new CorrosaLock cement solution provides chemical resistance to CO2 and minimizes the impact of cyclic loading on the cement barrier.

E&P Highlights: March 15, 2024

2024-03-15 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including a new discovery and offshore contract awards.

E&P Highlights: April 8, 2024

2024-04-08 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including new contract awards and a product launch.

TotalEnergies Starts Production at Akpo West Offshore Nigeria

2024-02-07 - Subsea tieback expected to add 14,000 bbl/d of condensate by mid-year, and up to 4 MMcm/d of gas by 2028.