Presented by:

Editor’s note: This is the second in a four-part series Oil and Gas Investor is featuring with Kenan-Flagler Energy Center at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill. Read part one here. Part three will appear in the October issue.

Trip and Kelly had been classmates at UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School where they both took the energy concentration. Thereafter, Trip went to work for a Texas oil and gas midstream company while Kelly took a job in sustainability and electric power in North Carolina. Three years passed and they met at a school reunion. It didn’t take long for sharp differences over the energy transition to surface:

Kelly: “I’m surprised you’re still working in a sunset industry. You always gave me the impression of wanting to work for a firm where you could spend a whole career.”

Trip: “You clearly haven’t been looking at the global energy outlooks. Both the U.S. Energy Information Administration and the International Energy Agency [IEA] have global oil and natural gas demand growing for decades.”

Kelly: “Don’t be so confident about those outlooks. Have you seen the number of places outlawing internal combustion engines? How about all the companies pledging to reach net-zero emissions within the next few decades? And the IEA is now saying we can’t afford new oil and gas investments if we’re serious about addressing climate. Moreover, just look at what’s been happening at Exxon Mobil Corp.—I mean seriously, do you think it will stop with just engine No.1?”

Trip: “Beware of politicians and CEOs making fashionable pledges they won’t be around to have to deliver.”

Kelly: “That’s the trouble with you oil industry people—you don’t really take the climate issue seriously. You talk about it but never spend any real money to address the needed transition. The messaging is all PR to defend your core business—just rabid greenwashing!”

Trip: “You should talk. Climate activists speak constantly about the timing urgency around climate but then turn around and block lots of things that would actually help, such as natural gas pipelines and nuclear plants. Your biggest piece of propaganda is that the world can decarbonize with wind, solar and batteries. Nothing gives the lie to your urgency claims like pretending China, India and the developing world can decarbonize that way. They can’t. And the longer you cling to that fiction, the more ‘precious’ time you waste before you finally get around to facing the tough issues and necessary tradeoffs.”

Kelly: “At least wind, solar, EVs and storage are making a zero carbon impact. If it was up to you in the oil industry, we’d still be debating whether climate is an issue while keeping gas guzzlers on the road.”

Trip: “Enjoy your Goldilocks renewables moment. I’ll enjoy seeing your resume circulate when the hidden problems, all the issues buried in today’s climate narrative, really surface.”

This discussion, fictitious though it is, takes a stab at surfacing what many actually think on both sides of the energy transition debate. It also illustrates the ongoing “dialogue of the deaf.” How true are these strongly felt views? Let’s unpack them and see if there is any sort of pathway to common ground.

One way to seek out that common ground is to explore the assumptions hidden inside each side’s narrative. Once these surface, the actual areas of disagreement can be discussed. There is also a need to acknowledge the self-interests and political strategies in play. These cause both sides to focus unstintingly on their own story lines. We’ll examine the hidden assumptions and associated stratagems below as regards to three large questions: 1) What is climate science saying that’s really settled? 2) How committed is the oil industry to participating in the energy transition? and 3) To what extent is the environmental community’s version of the energy transition unrealistic and/or internally contradictory?

How settled is the climate science?

There is a strong conviction within the environmental community, and increasingly the U.S. public at large, that the oil industry is filled with climate deniers. This, they assume, is overwhelmingly the product of an unwillingness to admit an inconvenient truth that threatens their business.

The reality is more nuanced and not just because an industry as large as oil and gas will encompass some diversity of views. The oil and gas industry has a strong scientific and technical basis. There is broad understanding of the greenhouse-gas (GHG) effect and acceptance that the earth is presently undergoing a warming trend. Moreover, more than one company board has brought in climate scientists from places such as MIT. They’ve looked at the range of possible scenarios, including some very scary ones if the more extreme projections play out. This journey now underpins the acknowledgements of climate risk found on energy company websites, in proxy material and in communications put out by groups such as the API.

“Over time, the industry actually has spent meaningful dollars on diversifications away from oil and gas. Many of these were broadly aligned with the energy transition.”

On the other hand, many in the industry continues to assume that the certainty touted by climate scientists is exaggerated. This view is based on not just self-interest, but on experience within their own industry. Many of their skeptical assumptions about climate science stem from their own attempts to model oil and gas projects. They’ve found that, to some degree, their own project models are almost always wrong.

Decades of experience have convinced them that modeling complex systems during long periods of time is hugely imprecise. Many assumptions must be made to compensate for areas where reliable historical data is thin. Then, variables don’t behave as expected, constants don’t stay constant and unanticipated factors radically realign what’s possible going forward. Here the industry’s technical knowledge also advises that the climate system is hugely complex, subject to many variables and is not well understood in key dimensions. Oil and gas executives also recall previous draconian forecasts, such as the 1970s Club of Rome study predicting the world would run out of natural resources by 2000 or the repeated forecasts of “peak oil” production—all of them hopelessly incorrect.

This perspective then directs the industry toward assuming that any forecast, climate outcomes included, is best treated as a probability exercise. Where do most of the outcomes tend to cluster, how big are the risk tails in the distribution? Policies, they believe, should be based on this kind of assessment. Actions and capital should then be allocated toward the better bets.

From this perspective, many conclude that tearing down the installed infrastructure providing some 80%-plus of the global economy’s energy and replacing it in a matter of decades seems not just a bad bet but an exercise in irrationality. It not only can’t be done, it shouldn’t be done based on what we know and don’t know.

The environmental community’s view assumes that climate science has solidified over the past three decades to the point where it is a reliable guide for action. Whereas climate science in the 1990s acknowledged multiple challenges in modelling, measurement and available data, there are now three decades of refinement ground into the research. This refinement has not substantially altered the outlook—continuous warming for the planet correlated with continued GHG emissions and a risk of various systems passing tipping points with dramatic harmful effects.

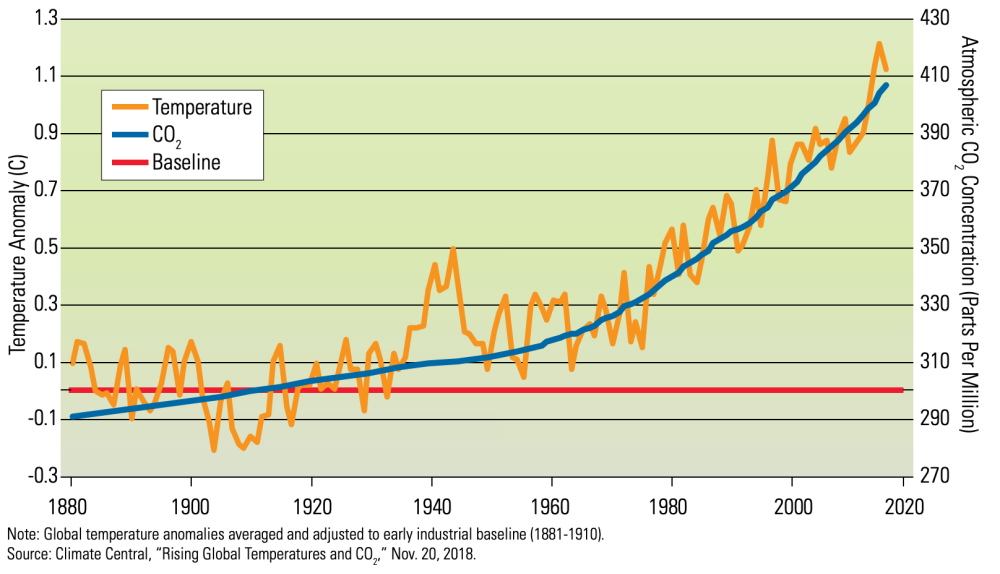

Chart No. 1, which plots the relationship between CO₂ concentrations and global temperature, 1880 to 2017, illustrates this view. The worst scenarios are truly dreadful. Here there is concern that if the earth’s ecosystem passes certain tipping points, there is no way back. Much of the scientific community that has studied the research supports this assessment as “state of the art.”

Moreover, timing matters. If the 2 C targets serve as the best starting point for a climate strategy discussion, the environmental community assumes there is little chance of achieving those goals without dramatic changes. Said differently, if the global economy wants to make sure the most damaging scenarios don’t come to pass, there is no time to waste. Serious decarbonization must begin now.

This view is connected to a third but barely acknowledged assumption. The environmental community knows that fossil fuels are entrenched as the basis for modern life. Economics, inertia, collateral issues—the list of factors likely to derail efforts to decarbonize is long. Some of the environmental community’s exaggeration and unwillingness to brook dissent stems from a view that the impetus for decarbonization could easily drain away if doubts are allowed to take hold. It believes that oil and gas industry opposition is one factor promoting such doubts.

In surveying this landscape, it becomes clearer that the environmental community sees the industry as both unconverted and untrustworthy on climate risk, while the industry sees the environmental community as uninterested in any discussion of the complexities. There are elements of validity in both views.

Oil and gas’ commitment

There are plenty of reasons for assuming that the industry is ambivalent about investing in the energy transition. There is the obvious reason that the transition threatens their core business. In most energy transition scenarios oil and gas becomes a consolidating industry heading toward a smaller footprint in some markets. More evidence of ambivalence is found within industry capital budgets. The environmental community has correctly noted that the industry spends only a small percentage of its capital funds on anything that can be called energy transition—be it research, pilot projects, at-scale projects or acquisitions. From 2010 to 2014, majors such as Exxon Mobil Corp., Chevron Corp. and Royal Dutch Shell Plc each spent an excess of $30 billion annually on oil and gas projects. Almost none of their spending could be characterized as energy transition focused.

This disconnect between what the industry spends on funding the transition and its messaging on things such as carbon taxes has convinced many that the industry is just playing defense to sustain its business.

However, other assumptions are at play in the industry’s tepid commitment to energy transition spending, and it would be valuable for environmental activists to pay heed to these beliefs. The first is that “green investments” are not that economically attractive. This assumption is partly based on prior experience. Over time, the industry actually has spent meaningful dollars on diversifications away from oil and gas. Many of these were broadly aligned with the energy transition. After OPEC nationalized its Middle East reserves, Exxon Mobil launched Exxon Enterprises to diversify. It includes a solar company, a nuclear company and Reliance Electric. None of it paid off, and all of it was divested at a loss by 1986. BP too has spent considerable money “going green” since 1998. None of it has resulted in a material new business or a return above BP’s cost of capital. Both Total SA and Shell have initiated small green investments, but their major strategy shift has been from oil toward natural gas. Bottom line: No oil company has successfully diversified into a material green business with returns in line with its historic performance. On the contrary, the industry’s green investments have on average destroyed capital.

There are basic reasons why this is so. Commercializing new technologies typically produces large initial losses. This means fossil fuel firms investing in the energy transition have a choice: 1) they can be a “follower” into established energy transition technologies where they have no competitive advantage and realize commodity-type returns at best; or 2) they can attempt to develop proprietary technology that promises higher returns but involves both high risk and likely startup losses. To date, most industry players, remembering their earlier ventures, have been ambivalent about both paths.

“The industry will have to grow further into its role as part of the solution to meeting ‘the dual challenge’ of growing energy supplies while sharply reducing carbon emissions.”

There is another assumption that causes industry ambivalence, and it involves issues on which the environmental community could be helpful. The assumption is that the green pathways open to it will require massive amounts of government support, which cannot be relied upon long term. The industry sees almost all energy transition investment paths as “out of the money” versus current technology/production.

Wind/solar returns come in single digits. Storage is barely economic in selected locations. Biodiesel from soybean oil is 50%-plus more expensive than normal diesel. Hydrogen, green or blue, cannot come close to competing with natural gas. Carbon capture is a pure cost sinkhole unless it can be quickly routed into EOR. That may work in Texas but is of little help for ethanol plants in Iowa or power plants in New England.

These facts render all energy transition pathways dependent on subsidies, tax credits and mandates that reward their low carbon attributes. For example, the National Petroleum Council recently completed a massive study of carbon capture. It concluded that carbon taxes, or the equivalent in the $90-plus per ton neighborhood, would be needed for carbon capture, utilization and sequestration (CCUS) to become economic. Such realities run directly into two other principles embedded in the oil industry’s DNA: 1) public policy is inherently volatile, subject to political winds and changes in administration; and 2) therefore, don’t invest in long-term businesses dependent upon government support for their returns.

If it could acknowledge these assumptions, the environmental community could make a major contribution enabling the industry to progress its energy transition technologies. Close inspection will show that energy transition research is one place where the industry has been spending meaningful capital. The environmental community could help energy transition research turn into commercial deployments by supporting a stronger political base for the support which these technologies will need. For this to happen, the environmental community will have to reconsider certain unrealistic assumptions and internal contradictions of its own.

RELATED:

Energy Transition Part I: Addressing Oil and Gas’ Bad Rap

Environmental community’s vision

The environmental community has been justly credited with putting the need for the energy transition on the global agenda and for propelling it forward through unstinting advocacy. It has been less successful in advancing a credible approach to the energy transition. Its approach, burdened with unrealistic assumptions and contradictions, is becoming an obstacle to progress.

The core problem here is a tension between the timing urgency, which the environmental community promotes, and its assumptions about feasible solutions. Said differently, the environmental community generally believes deep decarbonization must be accomplished during the next 10 to 15 years. It then assumes this can be achieved solely by installing wind/ solar and batteries for electricity and rolling out electric vehicles (EVs) for mobility.

These assumptions may prove woefully inadequate for the avowed goal of deep decarbonization. The list of issues inherent in this environmental community solution set is staggering. Vast sectors, such as aviation, heavy industry and trucking are left largely untouched. There are inherent problems of grid stability, which current battery storage technologies cannot presently solve. It assumes that recent declining renewable cost trends will continue even as a vast scale-up puts rising pressure on input costs for land, connections and raw materials such as lithium and copper. It further assumes that voters will be indefinitely content to pay for massive public sector support for less convenient and more costly forms of energy.

The environmental community’s solution set is really a U.S./Europe solution set, with China as an interesting energy transition laboratory.

The developing world’s energy transition dilemmas suggest deep contradictions in the environmental community’s underlying assumptions. No country on earth is doing more to promote adoption of renewables plus EVs than China. Some 50% of EVs are now sold in that market. Yet, China continues constructing three new coal plants per month to drive its economy. The spectacle of EVs running on “dirty electricity” is now fully on display in Chinese cities. If China, the most advanced and state-led developing nation, cannot even begin decarbonizing via renewables and EVs, what expectation can one have for the rest of the developing world? And, if the developing world keeps increasing its emissions output for another one to two decades, what should one make of the environmental community’s urgent appeals for the U.S. to decarbonize radically during that same period? If climate is a global problem, what is accomplished if one part of the world decarbonizes while another keeps increasing emissions?

How has the environmental community ended up in a position where there appears to be this large disconnect between the climate goals it espouses and the means it endorses? There

are several factors at play here, including a donor base attuned principally to stopping activities it considers damaging. However, one of the biggest factors is the environmental community’s assumption that the big challenge remains one of advocacy. More specifically, it involves convincing officials, regulators and the public that climate risk is both threatening and urgent. The environmental community then assumes that, once a sufficient consensus is created, solutions will follow.

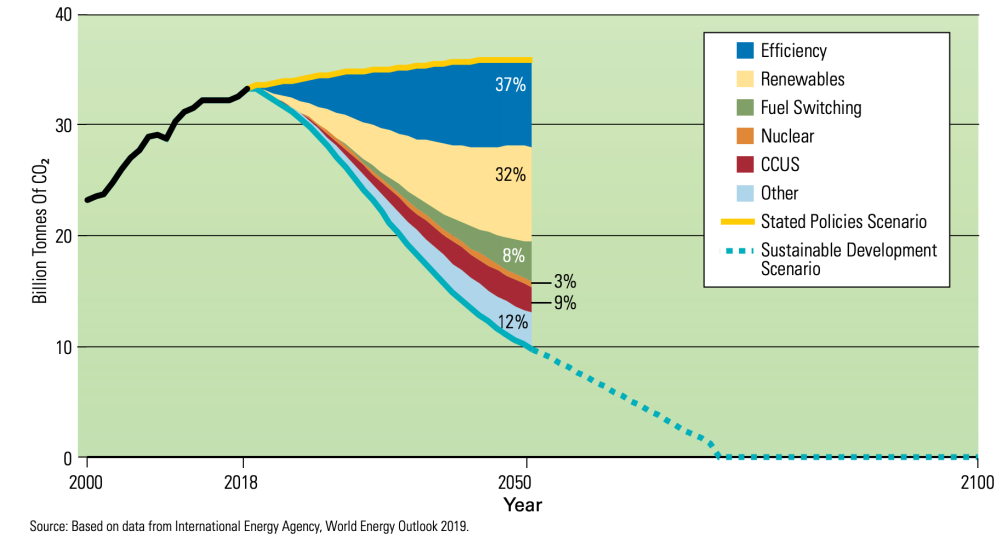

The lack of realism in this approach is underscored by a source that the environmental community often cites. Chart No. 2 shows the contributions that the IEA sees as necessary to put the global economy on a sustainable pathway to net-zero carbon emissions. Some 20% of those contributions must come from fuel switching, nuclear and CCUS. Another 37% must come from continued efficiency gains. Renewables provide less than a third of the necessary contributions despite an enormous expansion from today’s base. Finally, there is 12% that is simply unidentified. This is not an outlook that suggests that needed solutions are already on hand or can be assumed to arrive on time. Instead it suggests that the emerging challenge will be one of creating pathways for contributions from sources other than renewables.

Having spotlighted the many ways in which the industry and the environmental community assume different things about the issues and then talk past each other, is there any basis for their moving forward more collaboratively? Can greater awareness of how both sides think and some reconsideration of their own assumptions pave the way toward more constructive engagement?

Moving past out-moded assumptions

The first step toward seeing the energy transition through a clearer lens would be for all to agree that the climate advocacy battle has been largely won. There remains legitimate areas for discussion, e.g. the understanding of cloud formation, disagreements among different models, the understanding of feedbacks and natural variability, etc. Still, the consensus around limiting future CO₂ emissions is now broad and deep.

As proof, consider that The National Petroleum Council, in its 2019 report to the Secretary of Energy on Carbon Capture, developed its whole framework with reference to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s recent assessment reports and 2 C scenarios. Even nations such as China and India, who continue to prefer development as a national goal, acknowledge that the climate issue is real and deserving of attention. The global discussion now has moved onto what to do, how fast and at what cost.

Its advocacy success means that the environmental community should be undertaking its own “transition.” The focus needs to shift now from what should be stopped. To what are we prepared to enable? All transition energy options involve tradeoffs. Assembling enough of them is going to require choices—or more accurately, choosing enough options so that collectively they can make meaningful progress toward the decarbonization goal line.

This environmental community transition has only just begun. Attitudes toward nuclear power are a good test of willingness to weigh tradeoffs. On one side here, the Union of Concerned Scientists has evaluated the impairment to climate progress of allowing existing nuclear plants to retire and has advocated for safety and economic measures that will allow their continued operations. At the other end of the spectrum, the Sierra Club remains “unequivocally opposed to nuclear energy.”

A greater transition burden will fall on the oil and gas industry. It will have to get past underlying wishes that the climate issue would “just go away.” Pointing out the vital role of energy in daily life and in economic development, as valid as these perspectives are, must now be recognized as insufficient to address public concerns. The industry will have to grow further into its role as part of the solution to meeting “the dual challenge” of growing energy supplies while sharply reducing carbon emissions.

There are several dimensions of this necessary growth, but one deserves particular attention. The industry will have to move beyond its historic assumption not to invest in businesses that require public subsidies/support. As noted, all energy transition pathways are not “in the money” versus current carbon-emitting alternatives. This fact and the hazards inherent in commercializing new technologies make decarbonization businesses unattractive on their own. As a result, the industry will struggle to be part of the solution so long as it sees energy transition businesses that depend on state support as too risky to pursue.

Here is where a new form of engagement between the oil and gas industry and its environmental community critics could take place. An environmental community actively considering the climate/environmental tradeoffs and an industry searching for the most economic pathways toward decarbonization could have fruitful conversations about what to enable. Ironically, one interesting location where this engagement could take place could be the newly constituted Exxon Mobil board of directors. There, the new engine No. 1 directors could come to a deeper understanding of the commercial hurdles facing low carbon pathways and then help Exxon Mobil secure the fiscal support and stability needed to build out its new low carbon ventures business unit.

Environmental community/industry engagement could build an enduring consensus of public support for the best low carbon pathways. A stronger such consensus would then enable the industry to bring its considerable resources of technology, capital and operating know-hows to advance decarbonization on the backs of commercially attractive low carbon businesses.

Stephen Arbogast is the professor of the practice of finance and director of the Kenan-Flagler Energy Center at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill.

Recommended Reading

ProPetro Ups Share Repurchases by $100MM

2024-04-25 - ProPetro Holding Corp. is increasing its share repurchase program to a total of $200 million of common shares.

Baker Hughes Hikes Quarterly Dividend

2024-04-25 - Baker Hughes Co. increased its quarterly dividend by 11% year-over-year.

Weatherford M&A Efforts Focused on Integration, Not Scale

2024-04-25 - Services company Weatherford International executives are focused on making deals that, regardless of size or scale, can be integrated into the business, President and CEO Girish Saligram said.

Range Resources Holds Production Steady in 1Q 2024

2024-04-24 - NGLs are providing a boost for Range Resources as the company waits for natural gas demand to rebound.

Hess Midstream Increases Class A Distribution

2024-04-24 - Hess Midstream has increased its quarterly distribution per Class A share by approximately 45% since the first quarter of 2021.